pot; and old ladies, who should know better, nearly

choke themselves by too rapid a consumption of glace

a la vanille. And if Rangoon, to the annual pilgrim,

bulk's in this way as a kind of material paradise, it is

also associated in his mind with dangers he must guard

against; such as the trite Shway-lain, the Shan-lain,

and the Pyanpay. The Pyanpay involves the temporary

abduction of a child or of one of the waOg gOo n bullocks,'

and the payment of a price by the distracted owner for

its recovery. Young ladies who have come to worship

at the pagoda, remind themselves that Rangoon is a

wicked city, and the knowledge that some dashing

young fellow may carry them off in a fast cab adds a

thrill of excitement to their simple pleasures. Every

smart young fellow who throws an eye at a pretty girl

looms up in her timid imagination as the abductor of

tradition.

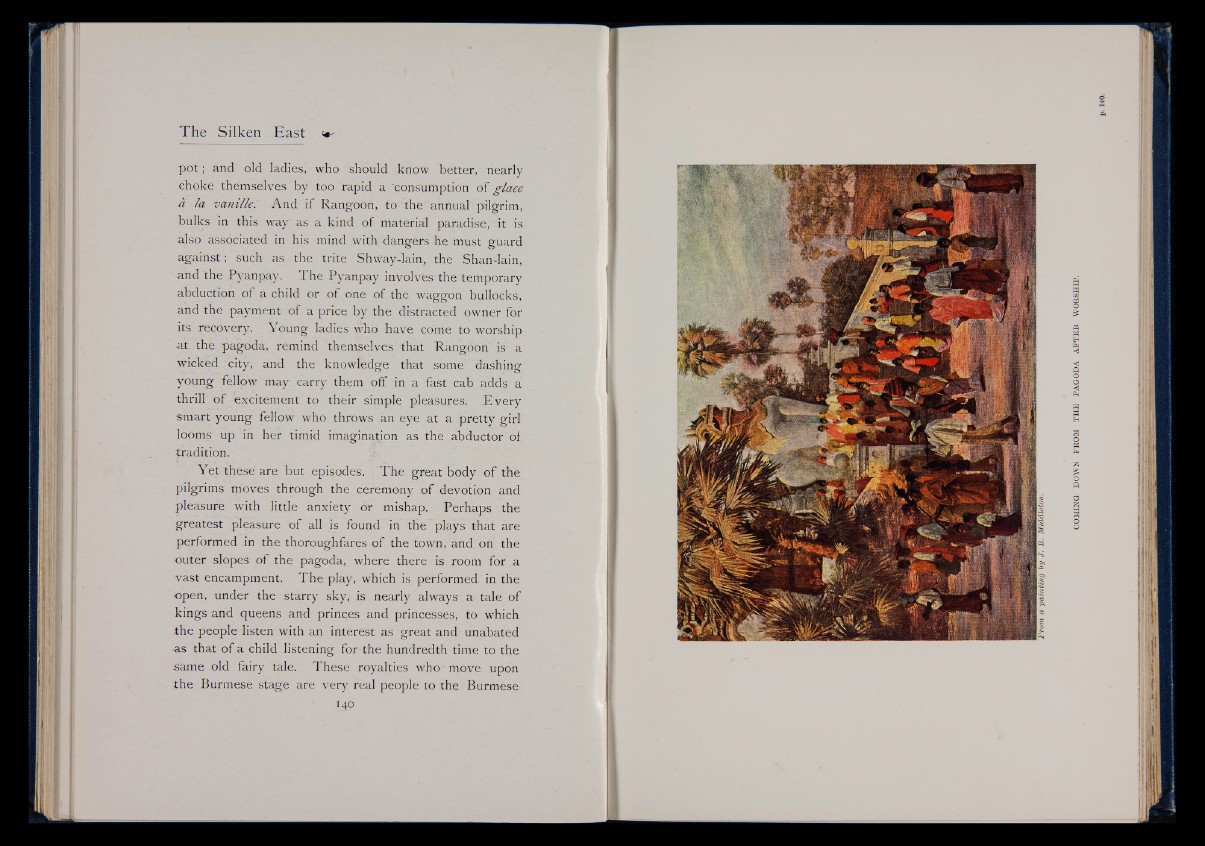

Yet these are but episodes. The great body of the

pilgrims moves through the ceremony of devotion and

pleasure with little anxiety or mishap. Perhaps the

greatest pleasure of all is found in the plays that are

performed in the thoroughfares of the town, and on the

outer slopes of the pagoda, where there is room for a

vast encampment. The play, which is performed in the

open, under the starry sky, is nearly always a tale of

kings and queens and princes and princesses, to which

the people listen with an interest as great and unabated

-as that of a child listening for the hundredth time to the

same old fairy tale. These royalties who move upon

the Burmese stage are very real people to the Burmese

140