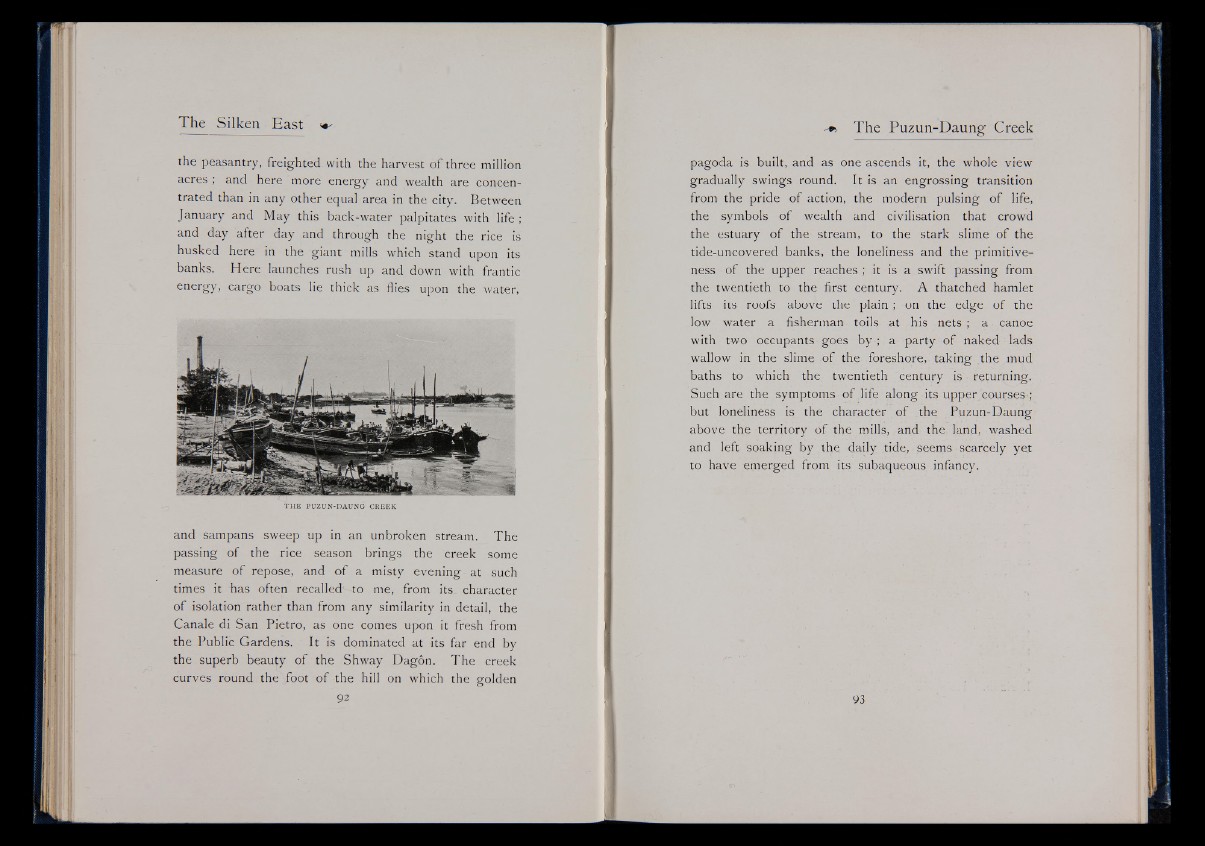

the peasantry, freighted with the harvest of three million

acres ; and here more energy and wealth are concentrated

than in any other equal area in the city. Between

January and May this back-water palpitates with life ;

and day after day and through the night the rice is

husked here in the giant mills which stand upon its

banks. Here launches rush up and down with frantic

energy, cargo boats lie thick as flies upon the water,

TH E PU ZUN -DAUN G CR E EK

and sampans sweep up in an unbroken stream. The

passing of the rice season brings the creek some

measure of repose, and of a misty evening at such

times it has often recalled to me, from its character

of isolation rather than from any similarity in detail, the

Canale di San Pietro, as one comes upon it fresh from

the Public Gardens. It is dominated at its far end by

the superb beauty of the Shway Dagon. The creek

curves round the foot of the hill on which the golden

92

pagoda is built, and as one ascends it, the whole view

gradually swings round. It is an engrossing transition

from the pride of action, the modern pulsing of life,

the symbols of wealth and civilisation that crowd

the estuary of the stream, to the stark slime of the

tide-uncovered banks, the loneliness and the primitiveness

of the upper reaches ; it is a swift passing from

the twentieth to the first century. A thatched hamlet

lifts its roofs above the plain ; on the edge of the

low water a fisherman toils at his nets ; a canoe

with two occupants goes by ; a party of naked lads

wallow in the slime of the foreshore, taking the mud

baths to which the twentieth century is ■ returning.

Such are the symptoms of life along its upper courses-;

but loneliness is the character of the Puzun-Daung

above the territory of the mills, and the, land, washed

and left soaking by the daily tide, seems scarcely yet

to have emerged from its subaqueous infancy.