the water’s edge. At Thayetmyo, I pass from all the

gracious circumstances of Burmese life to a town born

of half a century of foreign military tenure. The main

street along the banks of the river is a low-type reproduction

of an Indian bazaar; “brick houses, built in

execrable taste, flank it on either hand ; natives of India

flock in it, and the Burman here looks like a stranger

in his own land. Stray pagodas, elbowed by court-

houses and sentry boxes, reflect in their derelict

appearance the change that has come over the settlement.

It is in many ways a disagreeable metamorphosis;

most of all, perhaps, in the warning it conveys of a

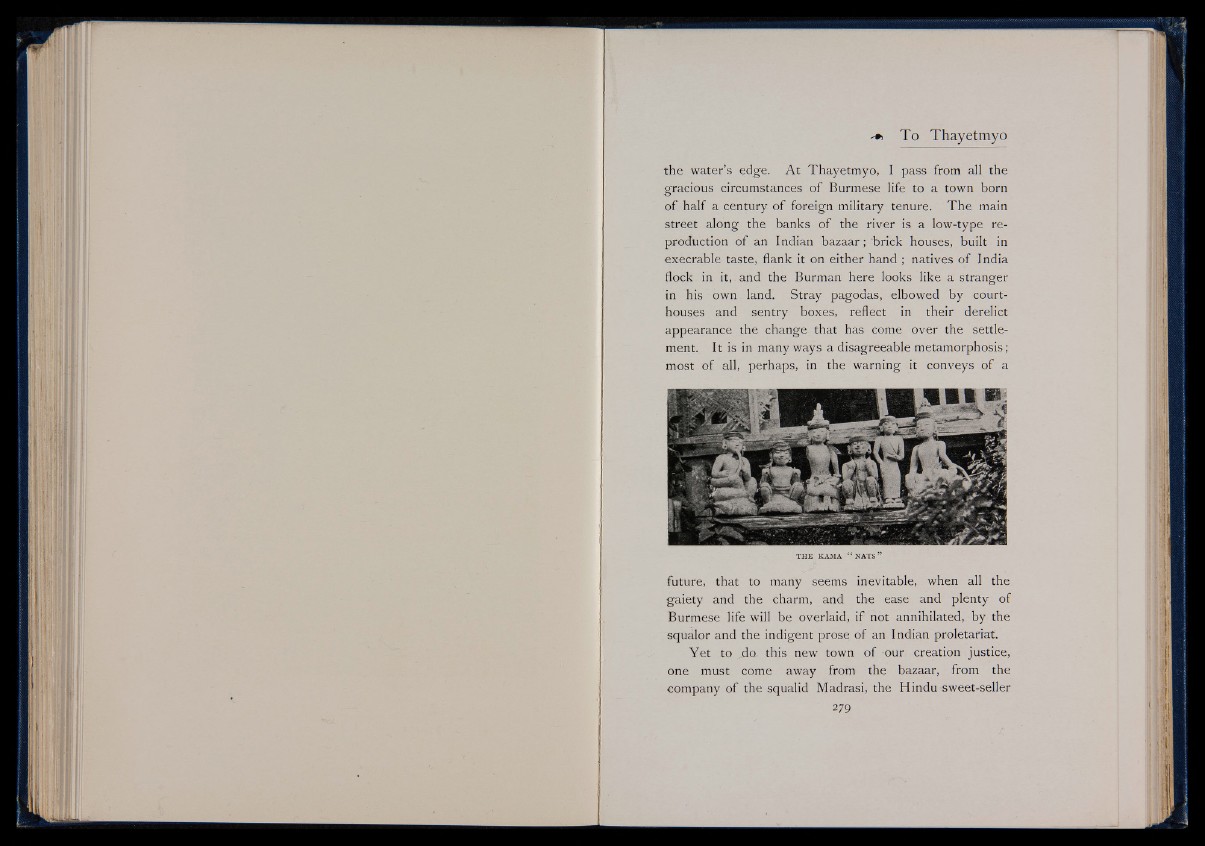

TH E K AM A “ N A TS B

future, that to many seems inevitable, when all the

gaiety and the charm, and the ease and plenty of

Burmese life will be overlaid, if not annihilated, by the

squalor and the indigent prose of an Indian proletariat.

Yet to jdo this new town of our creation justice,

one must come away from the bazaar, from the

company of the squalid Madrasi, the Hindu sweet-seller

2 79