river makes a splendid curve, and the waste of waters

looks like the opening of a sea.

At Henzada the people are busy at prayer, and

the chant of the worshippers is borne in measured

cadence over the dark face of the river. Within, the

raised highways are lined with the trays of Burmese

maidens, whose clear brains were meant for the business

of life, as their eyes, dark and lustrous, were

assuredly meant for love. Near at hand the rollicking

Chinaman does a roaring trade at the eating-houses

and liquor-shops. Small boys play at marbles on the

highway in the thick of the traffic. The wind blows

where it lists, amongst the stately palms and the

tinkling summits of monasteries and fanes.

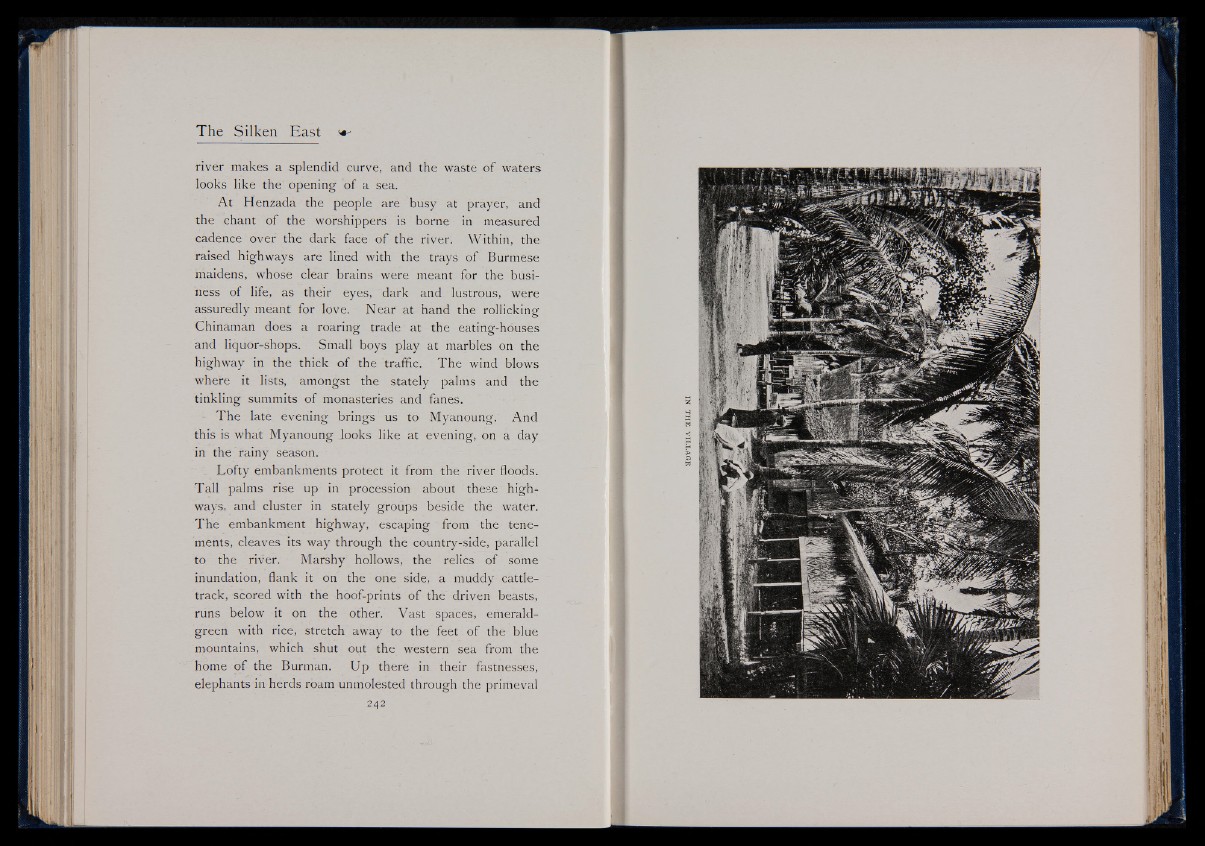

The late evening brings us to Myanoung. And

this is what Myanoung looks like at evening, on a day

in the rainy season.

Lofty embankments protect it from the river floods.

Tall palms rise up in procession about these highways,

and cluster in stately groups beside the water.

The embankment highway, escaping from the tenements,

cleaves its way through the country-side, parallel

to the river. Marshy hollows, the relics of some

inundation, flank it on the one side, a muddy cattle-

track, scored with the hoof-prints of the' driven beasts,

runs below it on the other. Vast spaces, emerald-

green with rice, stretch away to the feet of the blue

mountains, which shut out the western sea from the

home of the Burman. Up there in their fastnesses,

elephants in herds roam unmolested through the primeval

242