all its burden, the driver stands up and calls to his cattle

by name. They make a splendid, frantic effort, go down

on their knees, recover, and so come panting out of the

slough in which they have been all but entombed. Such

is the Burman unmetalled highway at this season, after

three days of fine weather.

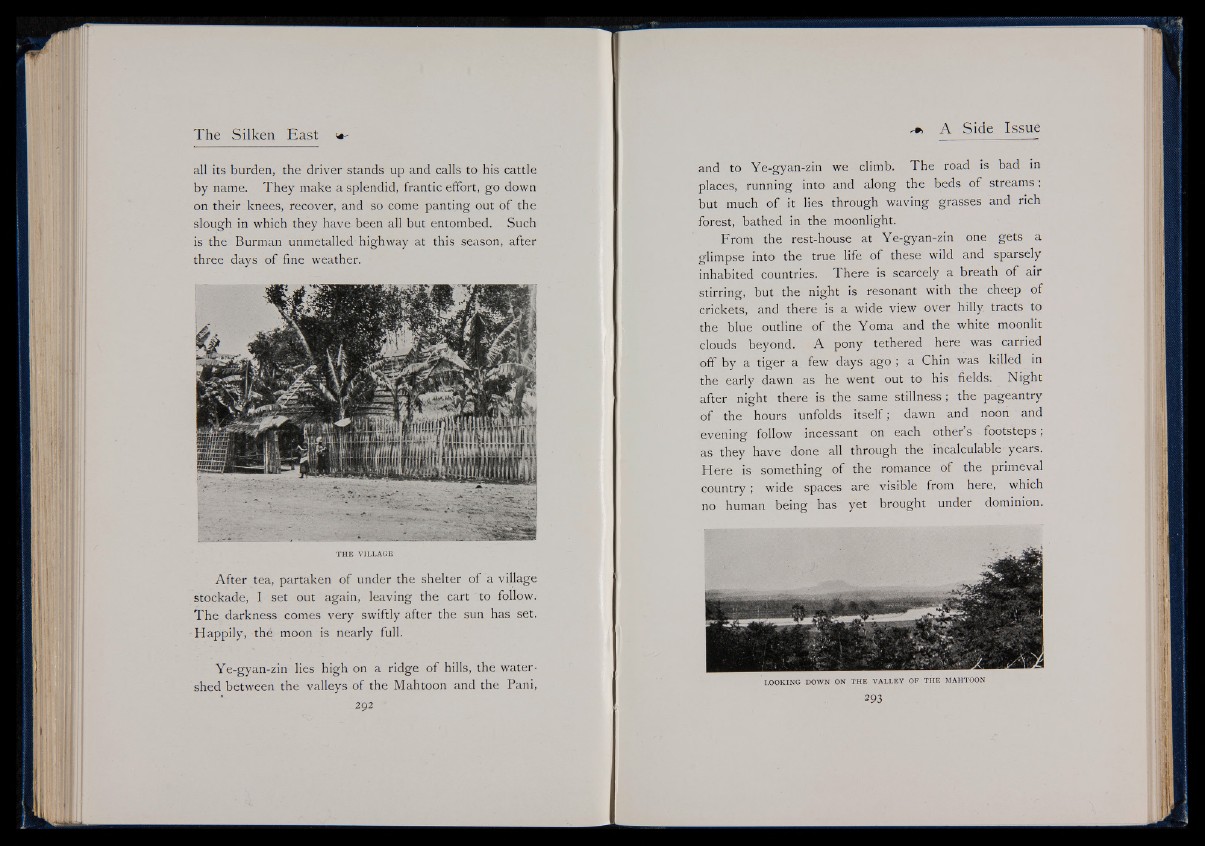

T H E V IL LA G E

After tea, partaken of under the shelter of a village

stockade, I set out again, leaving the cart to follow.

The darkness comes very swiftly after the sun has set.

Happily, thé moon is nearly full.

Ye-gyan-zin lies high on a ridge of hills, the watershed

between the valleys of the Mahtoon and the Pani,

292 -

and to Ye-gyan-zin we climb. The road is bad in

places, running into and along the beds of streams ;

but much of it lies through waving grasses and rich

forest, bathed in the moonlight.

From the rest-house at Ye-gyan-zin one gets a

glimpse into the true life of these wild and sparsely

inhabited countries. There is scarcely a breath of air

stirring, but the night is resonant with the cheep of

crickets, and there is a wide view over hilly tracts to

the blue outline of the Yoma and the white moonlit

clouds beyond. A pony tethered here was carried

off by a tiger a few days ago ; a Chin was killed in

the early dawn as he went out to his fields. Night

after night there is the same stillness ; the pageantry

of the hours unfolds itself; dawn and noon and

evening follow incessant on each other’s footsteps;

as they have done all through the incalculable years.

Here is something of the romance of the primeval

country ; wide spaces are visible from here, which

no human being has yet brought under dominion.

LO O K ING DOWN ON TH E V A L L E Y OF TH E MAHTOON

293