Happily it is not all new. It is served by an

immemorial river upon whose bosom a great life pulses ,

it is dominated by an edifice whose stateliness and

beauty are unsurpassed in Burma; and in its streets

fifty races gather to give it picturesqueness. Unlike

most Eastern cities, it is devoid of mystery. Its streets

lie open to the eye, its life moves much upon the

surface. Superficial visitors are apt to pass it by as

of little interest. Yet there is much in it that will

“ repay investigation.”

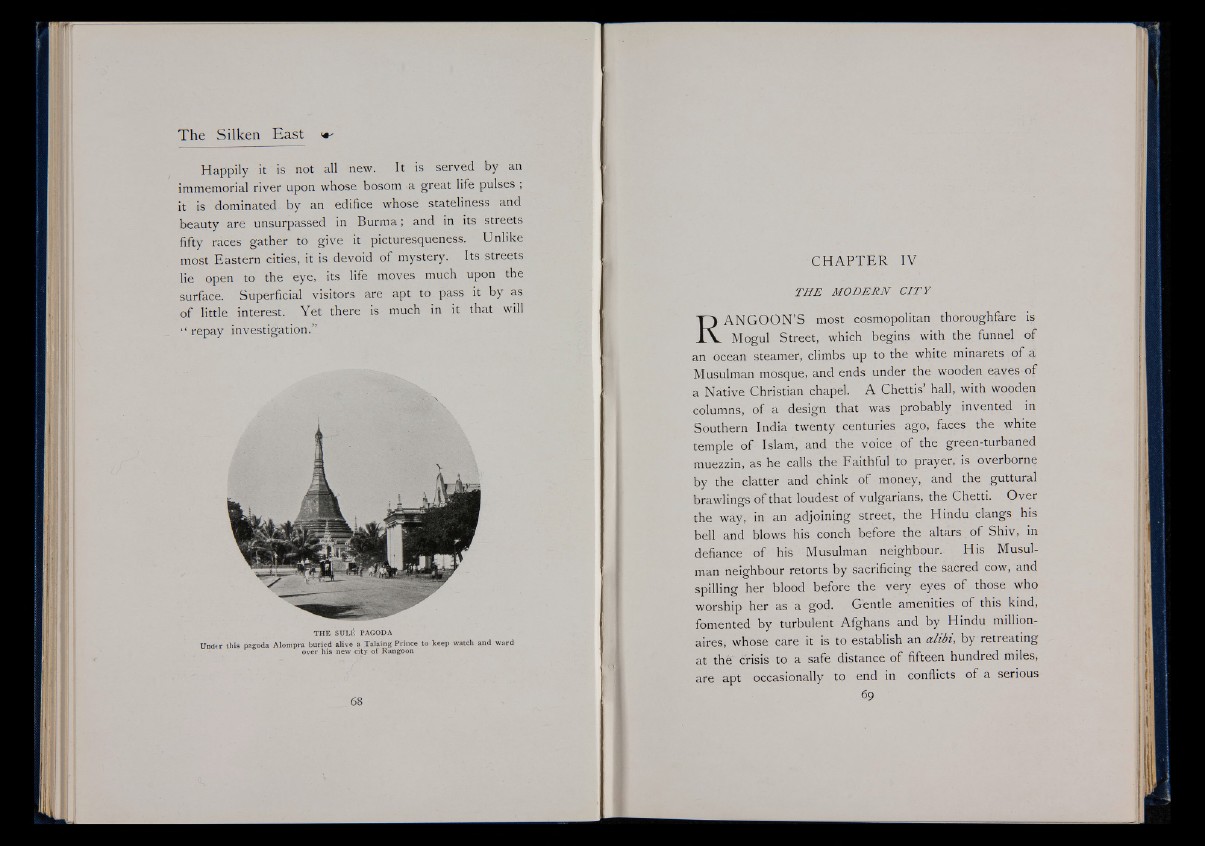

TH E SU LE PAGODA

U n d e r th is p a g o d a A lom p r a b u ried a liv e a T a la in g P r in c e to k e e p w a tch an d w a rd

o v e r h i s n ew c i ty o f R a n g o o n

CH A P T E R IV

T H E M O D E R N C I T Y

R

AN G O O N ’S most cosmopolitan thoroughfare is

Mogul Street, which begins with the funnel of

an ocean steamer, climbs up to the white minarets of a

Musulman mosque, and ends under the wooden eaves of

a Native Christian chapel. A Chettis’ hall, with wooden

columns, of a design that was probably invented in

Southern India twenty centuries ago, faces the white

temple of Islam, and the voice of the green-turbaned

muezzin, as he calls the Faithful to prayer, is overborne

by the clatter and chink of money, and the guttural

brawlings of that loudest of vulgarians, the Chetti. Over

the way, in an adjoining street, the Hindu clangs his

bell and blows his conch before the altars of Shiv, in

defiance of his Musulman neighbour. His Musulman

neighbour retorts by sacrificing the sacred cow, and

spilling her blood before the very eyes of those who

worship her as a god. Gentle amenities of this kind,

fomented by turbulent Afghans and by Hindu millionaires,

whose care it is to establish an alibi, by retreating

at the crisis to a safe distance of fifteen hundred miles,

are apt occasionally to end in conflicts of a serious

69