the space between, in hollows into which the river, at

its rising, rushes in, Chinese market gardeners are

toiling over rows of cabbages and beans. They go to

and fro in their blue clothes,

and large sun-hats, with cans

of water slung from poles,

across their shoulders. An

ingenious bamboo spout in

each can makes the water

splash in large silvery jets.

In all that a Chinaman does,

and has, there is somethingf

distinctive, from the decoration

of his house, to the pattern o f

his pipe and the spray of his

water-can. To understand him

one must clear one’s mind of

all prepossession.

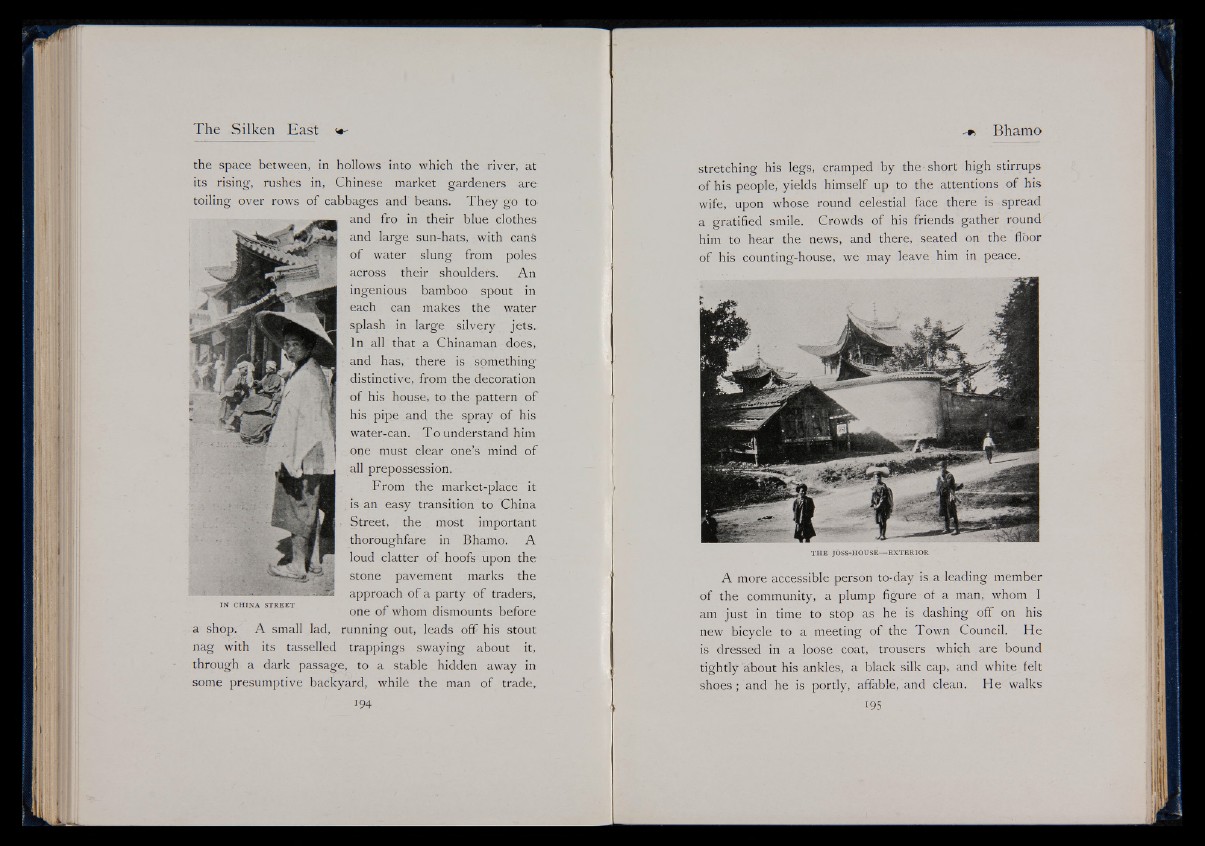

From the market-place it

is an easy transition to China

Street, the most important

thoroughfare in Bhamo. A

loud clatter of hoofs upon the

stone pavement marks the

approach of a party of traders,.

IN CH IN A ST R E E T r 1 i r one or whom dismounts before

a shop. A small lad, running out, leads off his stout:

nag with its tasselled trappings swaying about it,

through a dark passage, to a stable hidden away in

some presumptive backyard, whil6 the man of trade,

stretching his legs, cramped by the-short high stirrups

of his people, yields himself up to the attentions of his

wife, upon whose round celestial face there is spread

a gratified smile. Crowds of his friends gather round

him to hear the news, and there, seated on the floor

of his counting-house, we may leave him in peace.

TH E JOSS-HOUSE— EXTERIOR

A more accessible person to-day is a leading member

of the community, a plump figure of a man, whom I

am just in time to stop as he is dashing off on his

new bicycle to a meeting of the Town Council. He

is dressed in a loose coat, trousers which are bound

tightly about his ankles, a black silk cap, and white felt

shoes; and he is portly, affable, and clean. He walks