green and gold and purple. They are carved to their

summits and laden with numberless figures, each of

which is alive with action.

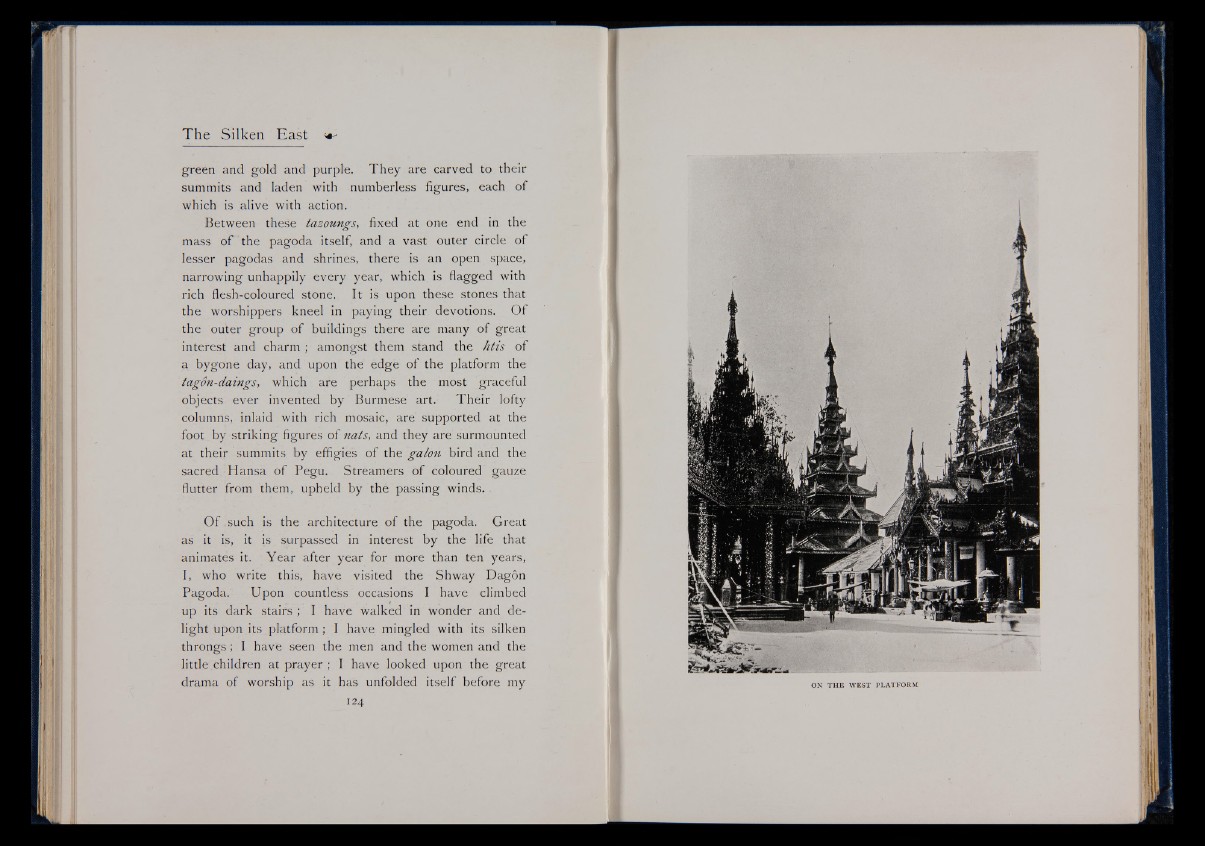

Between these tazoungs, fixed at one end in the

mass of the pagoda itself, and a vast outer circle of

lesser pagodas and shrines, there is an open space,

narrowing unhappily every year, which is flagged with

rich flesh-coloured stone. It is upon these stones that

the worshippers kneel in paying their devotions. O f

the outer group of buildings there are many of great

interest and charm ; amongst them stand the htis of

a bygone day, and upon the edge of the platform the

tagdn-daings, which are perhaps the most graceful

objects ever invented by Burmese art. Their lofty

columns, inlaid with rich mosaic, are supported at the

foot by striking figures of nats, and they are surmounted

at their summits by effigies of the galon bird and the

sacred Hansa of Pegu. Streamers of coloured gauze

flutter from them, upheld by the passing winds.

O f .such is the architecture of the pagoda. Great

as it is, it is surpassed in interest by the life that

animates it. Year after year for more than ten years,

I, who write this, have visited the Shway Dagon

Pagoda. Upon countless occasions I have climbed

up its dark stairs ; I have walked in wonder and delight

upon its platform ; I have mingled with its silken

throngs; I have seen the men and the women and the

little children at prayer ; I have looked upon the great

drama of worship as it has unfolded itself before my

124

ON TH E W EST PLATFO RM