silence. And I experience that strange and rare

emotion, of looking on at a world of which I form

no part j a new world of blue mountains, and wide

river, and placid calm, and unknown peoples, into which

I have dropped by some mysterious chance.

From Sampenago a sheltered way leads through

the village of Wethali, where lives a colony of Assamese,

the descendants of five hundred men-at-arms who came

over in the reign of Bodaw-phaya with the brother of

the King of Assam.

Among the races who throng, during the winter

months, the streets of Bhamo town, the Kachin with

his embroidered bag slung under one arm, ' his broad

half-naked rtfo/i thrown across his back, is not the-least

conspicuous; He comes- down from the hills -with

vegetables and fruits, and such sundries as a'tiger-skin,

some gold-dust, or a spinel pidked up in a watercourse,

and barters these in Bhamo' for the civilised commodities

he desires.

On the outskirts of the town, facing the highway,

stands the Kachin Waing, or caravanserai. It is not

the kind of place in which Haroun-al-Raschid might

have sojourned, for it consists'of little more than an

open shed in a yard enclosed by a bamboo fence. Yet

it is possessed of a primitive interest. The Kachin,

who carries his few necessaries with him, is content

with such shelter as a bare roof may afford, and it is

here in the Waing that he sleeps and feeds during his

brief visits to the town. Sometimes I go out there

in the early morning, while the night mists still brood

208

over the low pasture-lands o f Bhamo, to see him making

ready his breakfast. A small earthen pot is hung

like a gypsy kettle over a fire of slender twigs, and

seated before it, surrounded by the baskets of fruit

and vegetables he has brought down to sell, he leisurely

peels a pile of onions, dropping them one by one into

the simmering pot, in which a handful of small fry are

already stewing. His fellow near him pares small

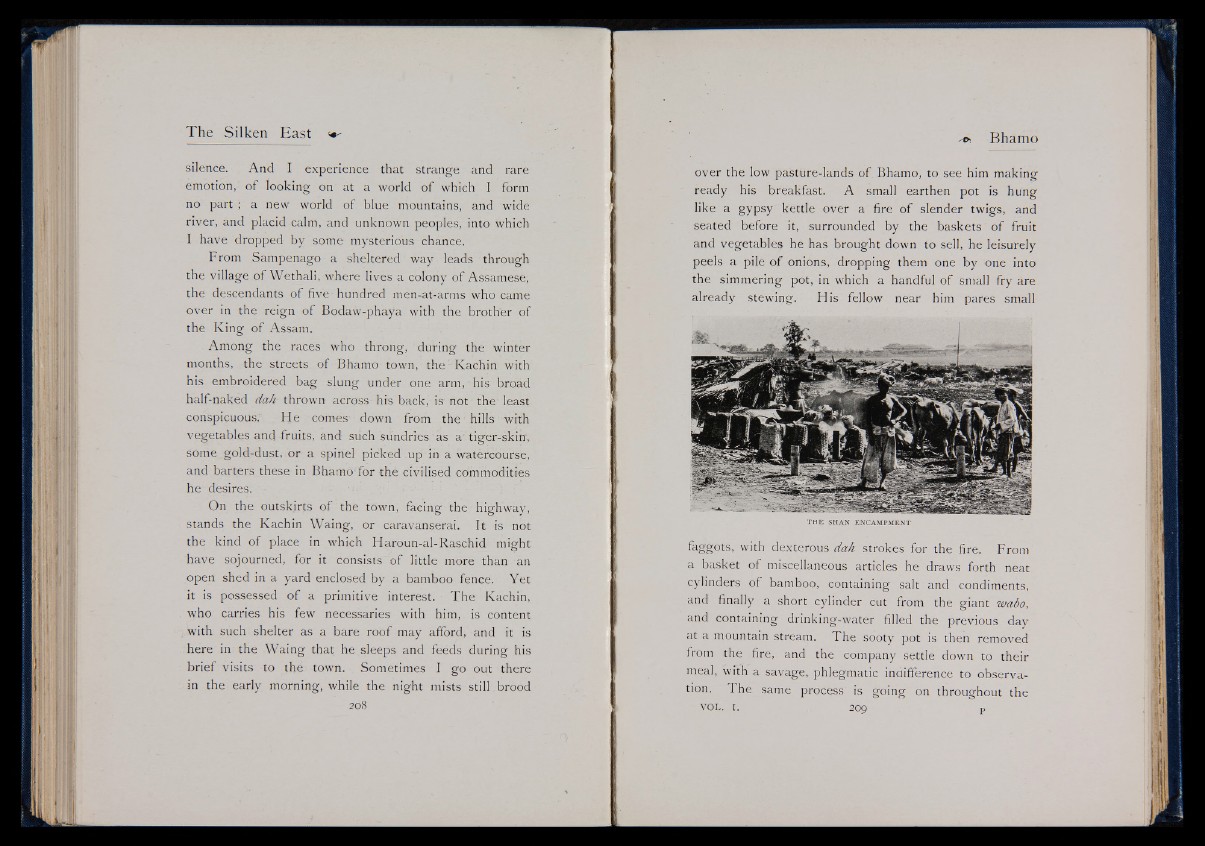

TH E SHAN ENCAMPMENT

faggots, with dexterous dah strokes for the fire. From

a basket of miscellaneous articles he draws forth neat

cylinders of bamboo, containing salt and condiments,

and finally a short cylinder cut from the giant wabo,

and containing drinking-water filled the previous day

at a mountain stream. The sooty pot is then removed

from the fire, and the company settle down to their

meal, with a savage, phlegmatic indifference to observation.

The same process is going on throughout the

vol. 1. 209 p