a woman to her finger-tips, and her fathers kneeling

attitude throws no shadow on her self-respect. Upstairs,

in the large living-room, with its bedsteads and mosquito

curtains, Mah Pan, the wife of the Saya, meets us, a

picture of what pretty girls in Burma come to ; fat

and round of face, with a calm eye and no illusions ;

dowager-like. There is no mystery in a Burmese house,

and the Saya welcoming me within, takes me beyond

this room into another, narrower but more cheerful,

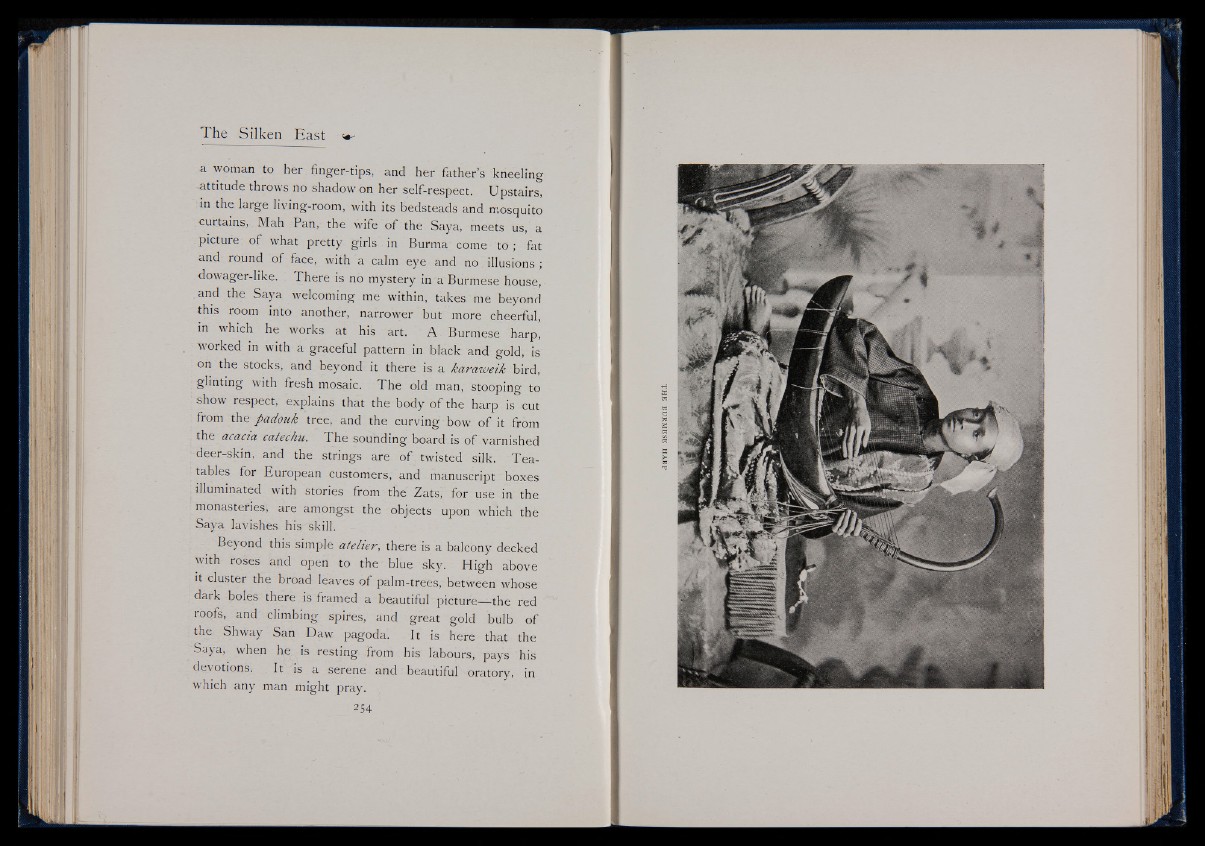

in which he works at his art. A Burmese harp,

worked in with a graceful pattern in black and gold, is

on the stocks, and beyond it there is a karaweik bird,

glinting with fresh mosaic. The old man, stooping to

show respect, explains that the body of the harp is cut

from the padouk tree, and the curving bow of it from

the acacia catechu. The sounding board is of varnished

deer-skin, and the strings are of twisted silk. Tea-

tables for European customers, and manuscript boxes

illuminated with stories from the Zats; for use in the

monasteries, are amongst the objects upon which the

Saya lavishes his skill.

Beyond this simple atelier, there is a balcony decked

with roses and open to the blue sky. High above

it cluster the broad leaves of palm-trees, between whose

dark boles there is framed a beautiful picture— the red

roofs, and climbing spires, and great gold bulb of

the Shway San Daw pagoda. It is here that the

Saya, when he. is resting from his labours, pays his

devotions. It is a serene and beautiful oratory, in

which any man might pray.

THE BURMESE HARP