great superiority of the iron-roofed monasteries over the

humble tenements of the peasantry ; and the prominent

house of the Chinaman, pushing his way to fortune.

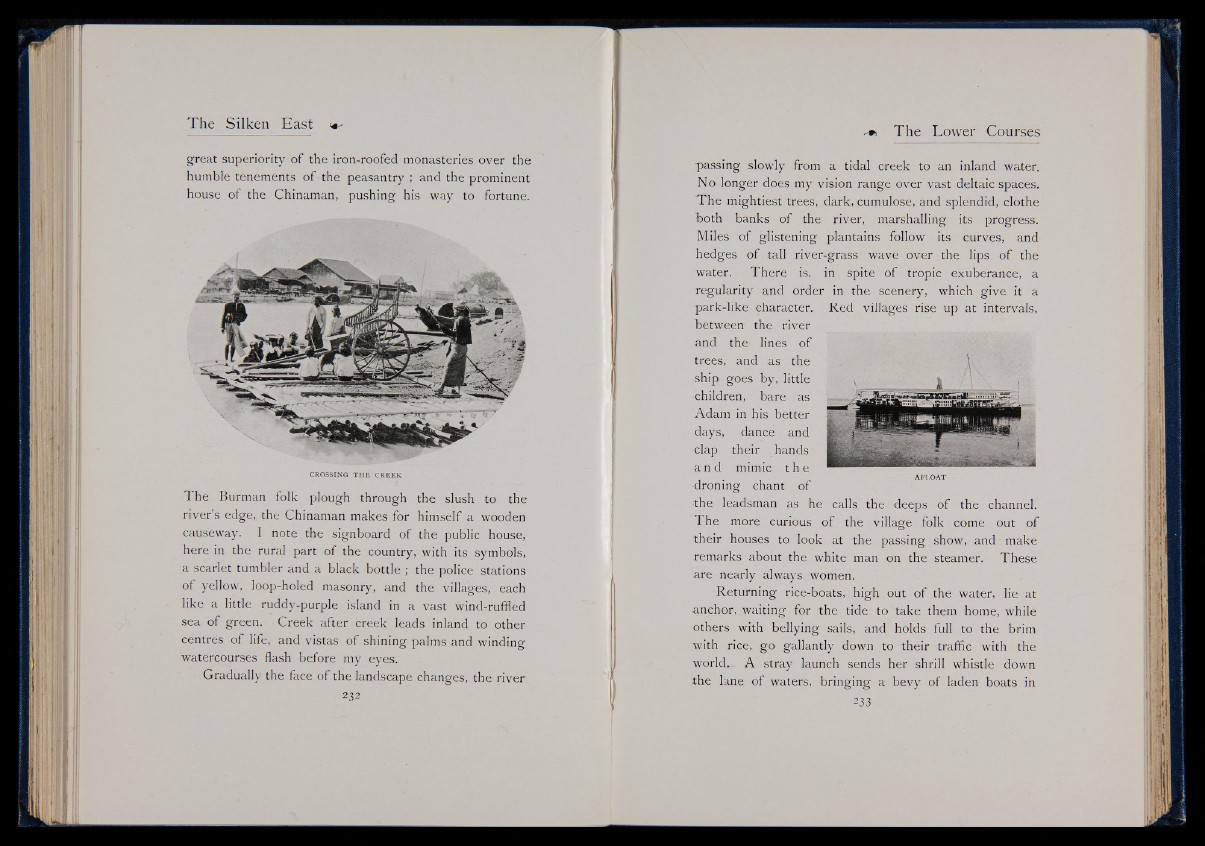

CROSSING TH E C R E EK

The Burman folk plough through the slush to the

river’s edge, the Chinaman makes for himself a wooden

causew'ay. I note the signboard of the public house,

here in the rural part of the country, with its symbols,

a scarlet tumbler and a black bottle ; the police stations

of yellow, loop-holed masonry, and the villages, each

like a little ruddy-purple island in a vast wind-ruffled

sea of green. Creek after creek leads inland to other

centres of life, and vistas of shining palms and winding

watercourses flash before my eyes.

Gradually the face of the landscape changes, the river

232

passing slowly from a tidal creek to an inland water.

No longer does my vision range over vast deltaic spaces.

T h e mightiest trees, dark, cumulose, and splendid, clothe

Both banks of the river, marshalling its progress.

Miles of glistening plantains follow its curves, and

hedges of tall river-grass wave over the lips of the

water. There is, in spite of tropic exuberance, a

regularity and order in the scenery, which give it a

park-like character.

Red villages rise up at intervals,

Between the river

and the lines of

trees, and as the

ship goes by, little

children, bare as

Adam in his better

days, dance and

clap their hands

a n d mimic th e

A F LO A T

droning chant of

the leadsman as he calls the deeps of the channel.

1 he more curious of the village folk come out of

their houses to look at the passing show, and make

remarks about the white man on the steamer. These

are nearly always women.

Returning rice-boats, high out of the water, lie at

anchor, waiting for the tide_ to take them home, while

others with bellying sails, and holds full to the brim

with rice, go gallantly down to their traffic with the

world,. A stray launch sends her shrill whistle down

the lane of waters, bringing a bevy of laden boats in