of the silk-weavers of Prome, and there is a whole

street of Kathes. Seeing that they are of Hindu

persuasion, it is no long way from them to the house

of a Brahmin. The master is away at Rangoon; but

his \yife, a comely woman, receives me. She laughs,

and says that if I am going to photograph her, she

must go in and change her dress. Her husband

keeps the school for the Manipuri children. She

looks like a Burman, but states that she and her

people keep to rules of caste, and only marry within

the proper limits. Buddhism has, at least, taught her

to come out from darkened chambers into the sunlight

o f life.

I go from her; to the house of a painter, and find

him busy, with his assistants, over a large canvas,

destined for a theatre. He does a considerable business

in portraits, which he achieves by painting splendid

backgrounds and fine clothes, and putting in for the

face a photograph. This compromise is eminently

satisfying to his customers, and it is certain that an

air of reality is imparted to the photographs by their

curious setting.

Burmese art is still in its infancy ; but it has this

of merit at least, that it is alive. A Burmese painter

is quite prepared to grapple with any subject, from a

sunset to a buffalo fight. Crude as his efforts are, it

has always given me pleasure to come into contact with

the Burmese painter. For he has the true spirit of

the artist. He will come when you send for him to

your house, clad in his best silk putsoe and whitest

260

muslin coat (his

manners b e i n g

the fine manners

of his race), and

he will sheko, and

crouch down on

t h e floor, an d

carry himself as

if . he had been

b r o u g h t up at

court. His air

will be o n e o f

the gravity that

befits ceremonial

occasions, and he

will say phaya

(“ my lord’) at

t h e p r o p e r

intervals. B u t

gradually as the

plan you put before

him unfolds

before his vision,

a light will come

into his eyes, a

new pose into his

stooping figure.

He will enter enthusiastically

into

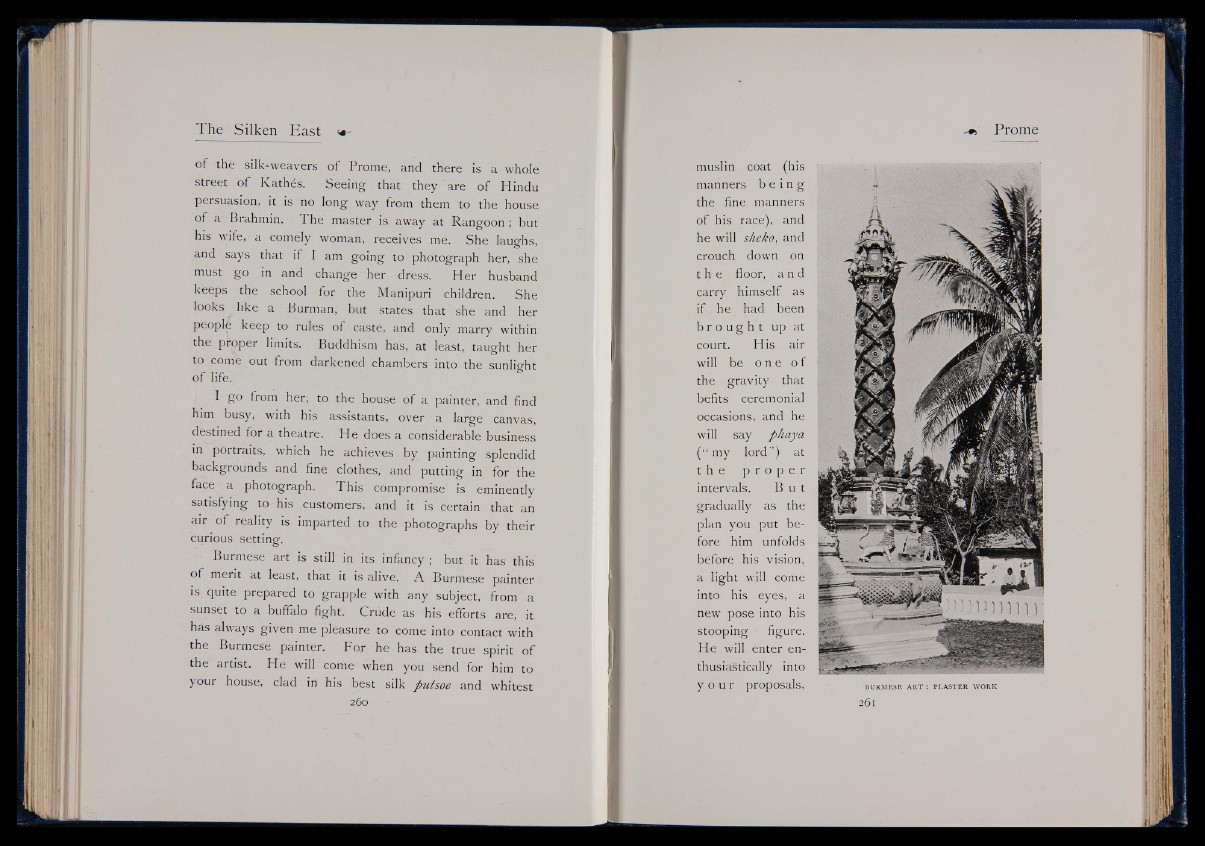

y o u r proposals, BURMESE A R T : P LA S TE R WORK

26l