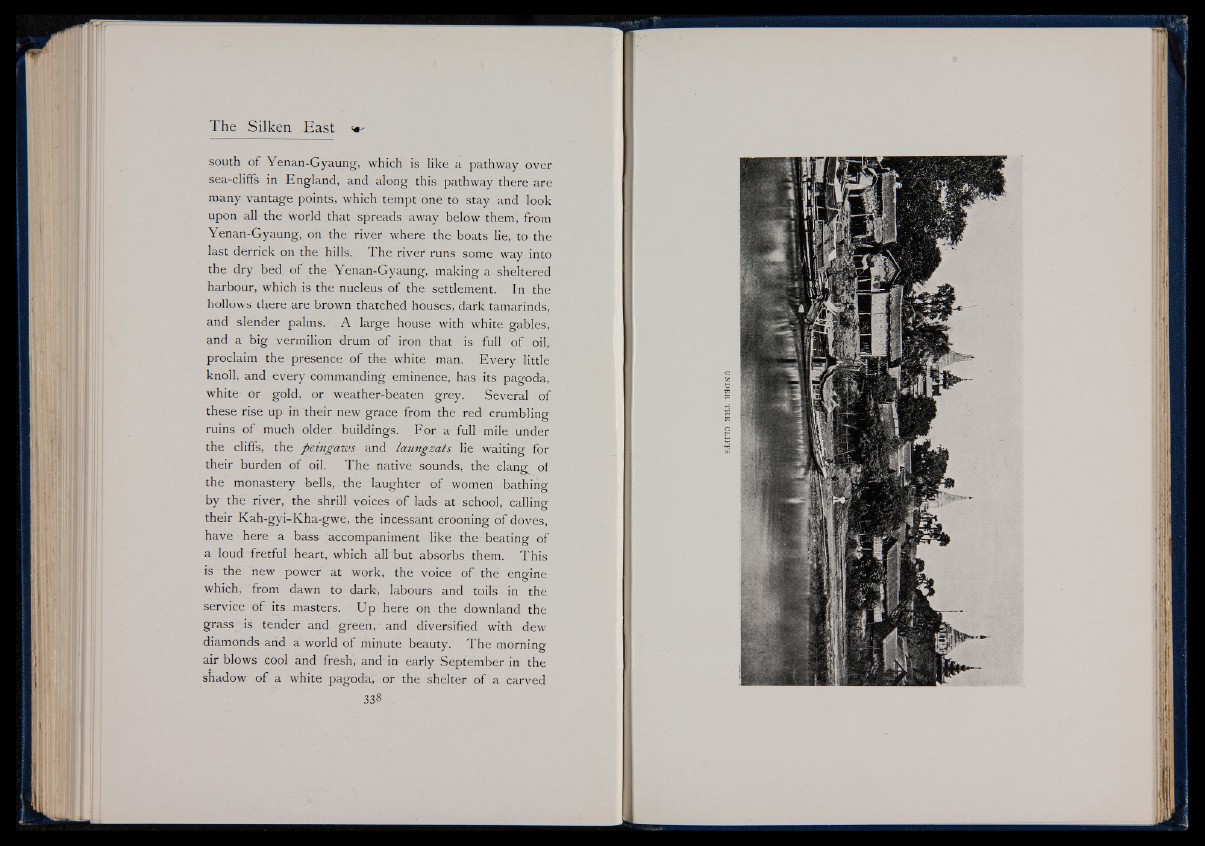

south of Yenan-Gyaung, which is like a pathway over

sea-clifis in England, and along this, pathway there are

many vantage points, which tempt one to stay and look

upon all the world that spreads away below them, from

Yenan-Gyaung, oh the river where the boats lie, to the

last derrick on the hills. The river runs some way into

the dry bed of the Yenan-Gyaung, making a sheltered

harbour, which is the nucleus of the settlement. In the

hollows there are brown thatched houses, dark tamarinds,

and slender palms. A large house with white gables,

and a big vermilion drum of iron that is full of oil,

proclaim the presence of the white man. Every little

knoll, and every commanding eminence, has its pagoda,

white or gold, or weather-beaten grey. Several of

these rise up in their new grace from the red crumbling

ruins of much older buildings. For a full mile under

the cliffs, the peingaws and laungzats lie waiting for

their burden of oil. The native sounds, the clangs of

the monastery bells, the laughter of women bathing

by the river, the shrill voices of lads at school, calling

their Kah-gyi-Kha-gwe, the incessant crooning of doves,

have here a bass accompaniment like the beating of

a loud fretful heart, which all but absorbs them. This

is the new power at work, the voice of the engine

which, from dawn to dark-, labours and toils in the

service of its masters. Up here on the downland the

grass is tender and green,' and diversified with dew

diamonds and a world of minute beauty. The morning

air blows cool and fresh, and in early September in the

shadow o f a white pagoda, or the shelter of a carved

UNDER THE C U F F S