justified in putting the offender to death. Examples

of laws dictated in this spirit have been already

quoted.

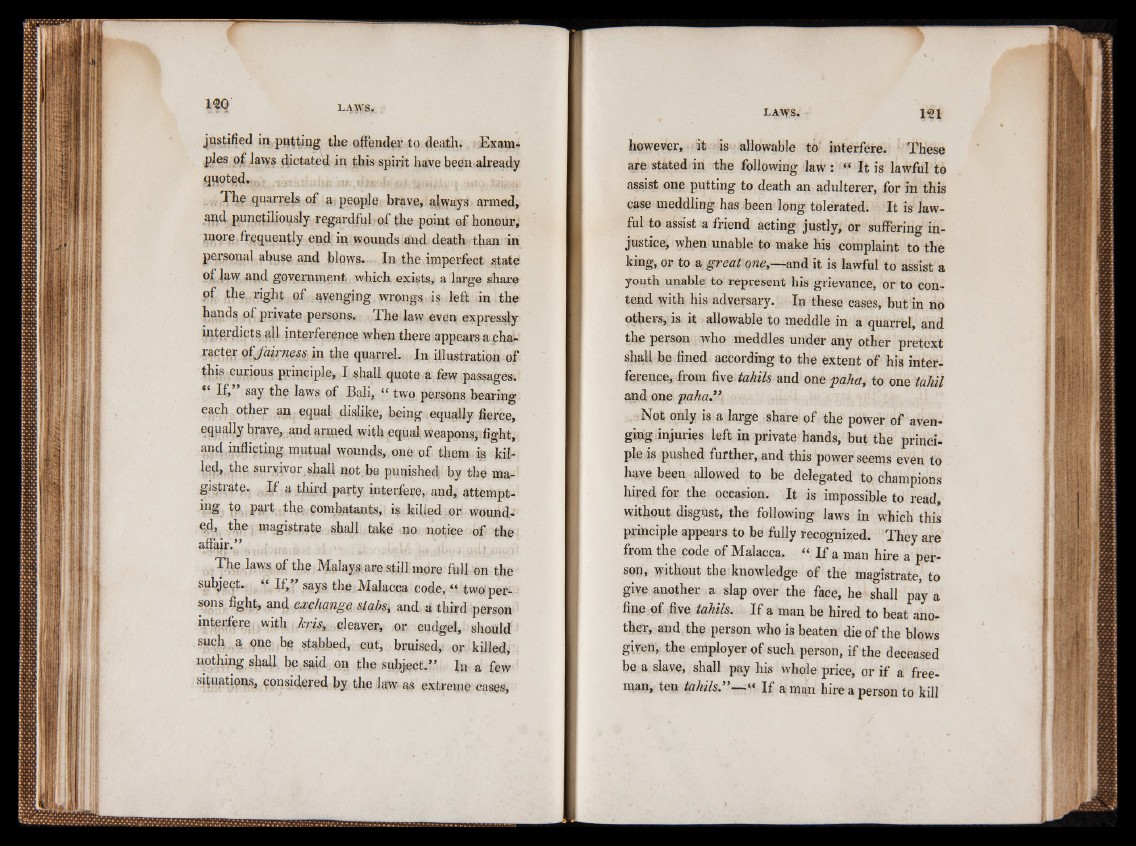

The quarrels of a people brave, always armed,

and punctiliously regardful of the point of honour,

more frequently end in wounds and death than in

personal abuse and blows. In the imperfect state

of law apd government which exists, a large share

of the right of avenging wrongs is left in the

h&P^s °f private persons. The law even expressly

interdicts all interference when there appears a cha-

ìacte.r of fairness in the quarrel. In illustration of

this curious principle, I shall quote a few passages.

If, say the laws, of Bah, “ two persons bearing

each other an equal dislike, being equally fierce,

equally brave, and armed with equal weapons, fight,

and inflicting mutual wounds, one of them is killed,

the survivor shall not be punished by the magistrate.

If a third party interfere, and, attempt-

pmt the combatants, is killed or wound-

erd, the j magistrate shall take no notice of thè

affair.”

The laws of the Malays are still more full on the

subject. “ If,” says the Malacca code, “ two persons

fight, and exchange slabs, and a third person

interfere with kris, cleaver, or cudgel, should

such a one be stabbed, cut, bruised, or killed,

nothing shall be said 011 the subject.” In a few

situations, considered by the Jaw as extreme cases,

however, it is allowable to interfere. These

are stated in the following law : “ It is lawful to

assist one putting to death an adulterer, for in this

case meddling has been long tolerated. It is lawful

to assist a friend acting justly, or suffering injustice,

when unable to make his complaint to the

king, or to a great one,—and it is lawful to assist a

youth unable to represent his grievance, or to contend

with his adversary. In these cases, but in no

others, is it allowable to meddle in a quarrel, and

the person who meddles under any other pretext

shall be fined according to the extent of his interference,

from five tahils and one paha, to one tahil

and one paha.”

Not. only is a large share of the power of avenging

injuries left in private hands, but the principle

is pushed further, and this power seems even to

have been allowed to be delegated to champions

hired for the occasion. It is impossible to read,

without disgust, the following laws in which this

principle appears to be fully recognized. They are

from the code of Malacca. “ If a man hire a per-

, knowledge of the magistrate, to

give another a slap over the face, he shall pay a

fine of five tahils. If a man be hired to heat another,

and the person who is beaten die of the blows

given, the employer of such person, if the deceased

be a slave, shall pay his whole price, or if a freeman,

ten tahils. — If a man hire a person to kill