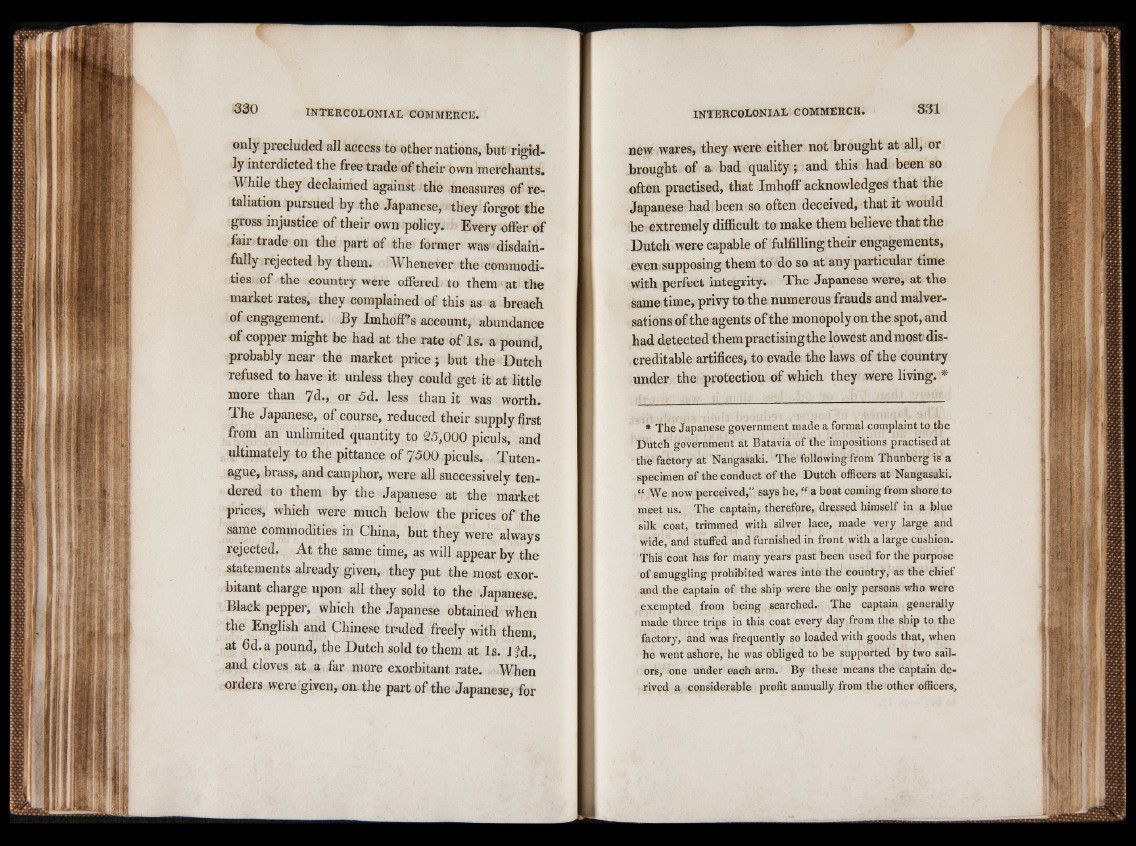

only precluded all access to other nations, but rigidly

interdicted the free trade of their own merchants.

While they declaimed against the measures of retaliation

pursued by the Japanese, they forgot the

gross injustice of their own policy. Every offer of

fair trade on the part of the former was disdainfully

rejected by them. Whenever the commodities

of the country were offered to them at the

market rates, they complained of this as a breach

of engagement. By ImhofPs account, abundance

of copper might be had at the rate of Is. a pound,

probably near the market price; but the Dutch

refused to have it unless they could get it at little

more than 7d*> or 5d. less than it was worth.

The Japanese, of course, reduced their supply first

from an unlimited quantity to 25,000 piculs, and

ultimately to the pittance of 7500 piculs. Tuten-

ague, brass, and camphor, were all successively tendered

to them by the Japanese at the market

prices, which were much below the prices of the

same commodities in China, but they were always

rejected. At the same time, as will appear by the

statements already given, they put the most exorbitant

charge upon all they sold to the Japanese.

Black pepper, which the Japanese obtained when

the English and Chinevse traded freely with them,

at 6d.a pound, the Dutch sold to them at Is. Jjd.,

and cloves at a far more exorbitant rate. When

orders were given, on4he part of the Japanese, for

?

new wares, they were either not brought at all, or

brought of a bad quality ; and this had been so

often practised, that Imhoff* acknowledges that the

Japanese had been so often deceived, that it would

be extremely difficult to make them believe that the

Dutch were capable of fulfilling their engagements,

even supposing them to do so at any particular time

with perfect integrity. The Japanese were, at the

same time, privy to the numerous frauds and malversations

of the agents of the monopoly on the spot, and

had detected them practising the lowest and most discreditable

artifices, to evade the laws of the country

under the protection of which they were living. *

* The Japanese government made a formal complaint to the

Dutch government at Batavia of the impositions practised at

the factory at Nangasaki. The following from Thunberg is a

specimen of the conduct of the Dutch officers at Nangasaki.

“ We now perceived,” says he, “ a boat coming from shore to

meet us. The captain, therefore, dressed himself in a blue

silk coat, trimmed with silver lace, made very large and

wideband stuffed and furnished in front with a large cushion.

This coat has for many years past been used for the purpose

of smuggling prohibited wares into the country, as the chief

and the captain of the ship were the only persons who were

exempted from being searched.- The captain generally

made three trips in this coat every day from the ship to the

factory, and was frequently so loaded with goods that, when

he went ashore, he was obliged to be supported by two sailors,

one under each arm. By these means the captain derived

a considerable profit annually from the other officers,