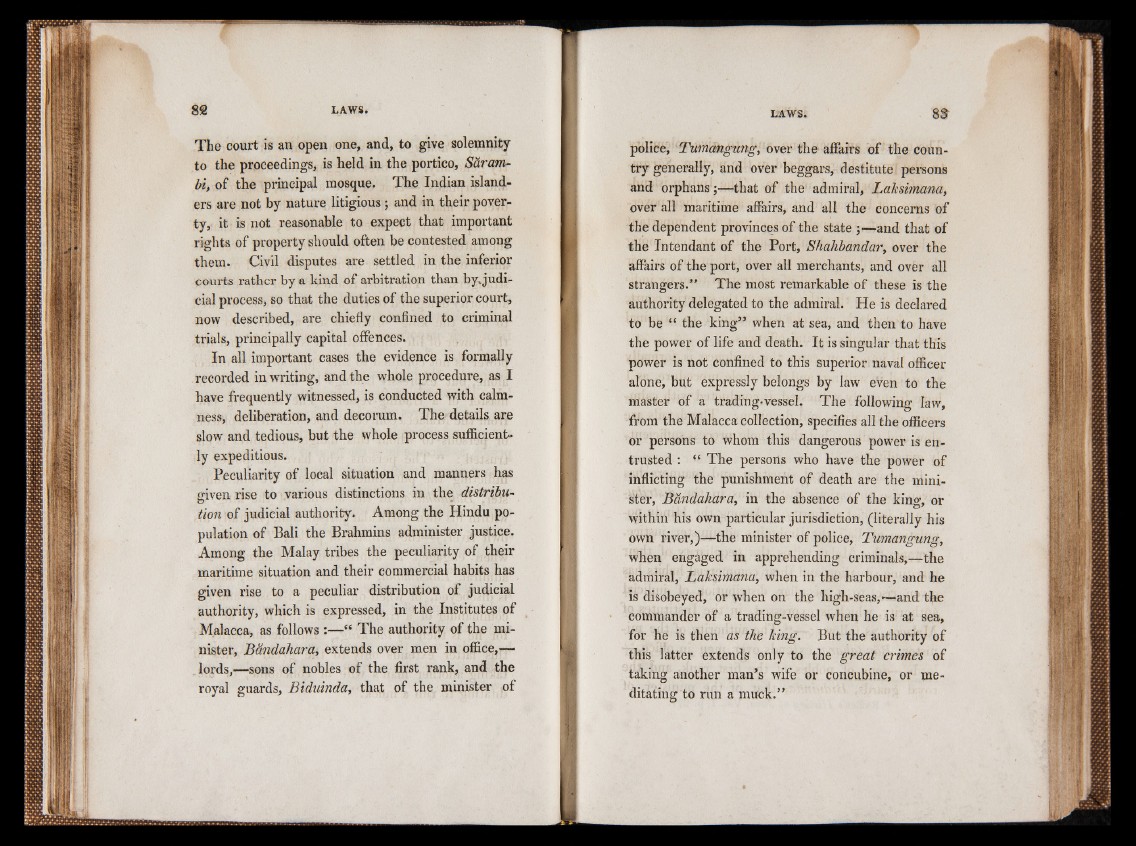

The court is an open one, and, to give solemnity

to the proceedings, is held in the portico, Saram-

bi, of the principal mosque. The Indian islanders

are not by nature litigious; and in their poverty,

it is not reasonable to expect that important

rights of property should often be contested among

them. Civil disputes are settled in the inferior

courts rather by a kind of arbitration than by. judicial

process, so that the duties of the superior court,

now described, are chiefly confined to criminal

trials, principally capital offences.

In all important cases the evidence is formally

recorded in writing, and the whole procedure, as I

have frequently witnessed, is conducted with calmness,

deliberation, and decorum. The details are

slow and tedious, but the whole process sufficiently

expeditious.

Peculiarity of local situation and manners has

«riven rise to various distinctions in the distribu- otion of judicial authority. Among the Hindu population

of Bali the Brahmins administer justice.

Among the Malay tribes the peculiarity of their

maritime situation and their commercial habits has

given rise to a peculiar distribution of judicial

authority, which is expressed, in the Institutes of

Malacca, as follows :—“ The authority of the minister,

Bandahara, extends over men in office,—

lords,—sons of nobles of the first rank, and the

royal guards, Biduinda, that of the minister of

police, Tumangung, over the affairs of the country

generally, and over beggars, destitute persons

and orphans;—that of the admiral, Laksimana,

over all maritime affairs, and all the concerns of

the dependent provinces of the state j—and that of

the Intendant of the Port, Shahbandar, over the

affairs of the port, over all merchants, and over all

strangers.” The most remarkable of these is the

authority delegated to the admiral. He is declared

to be “ the king” when at sea, and then to have

the power of life and death. It is singular that this

power is not confined to this superior naval officer

alone, but expressly belongs by law even to the

master of a trading-vessel. The following law,

from the Malacca collection, specifies all the officers

or persons to whom this dangerous power is entrusted

: “ The persons who have the power of

inflicting the punishment of death are the minister,

Bandahara, in the absence of the king, or

within his own particular jurisdiction, (literally his

own river,)—the minister of police, Tumangung,

when engaged in apprehending criminals,—the

admiral, Laksimana, when in the harbour, and he

is disobeyed, or when on the high-seas,-—and the

commander of a trading-vessel when he is at sea,

for he is then as the king. But the authority of

this latter extends only to the great crimes of

taking another man’s wife or concubine, or meditating

to run a muck.”