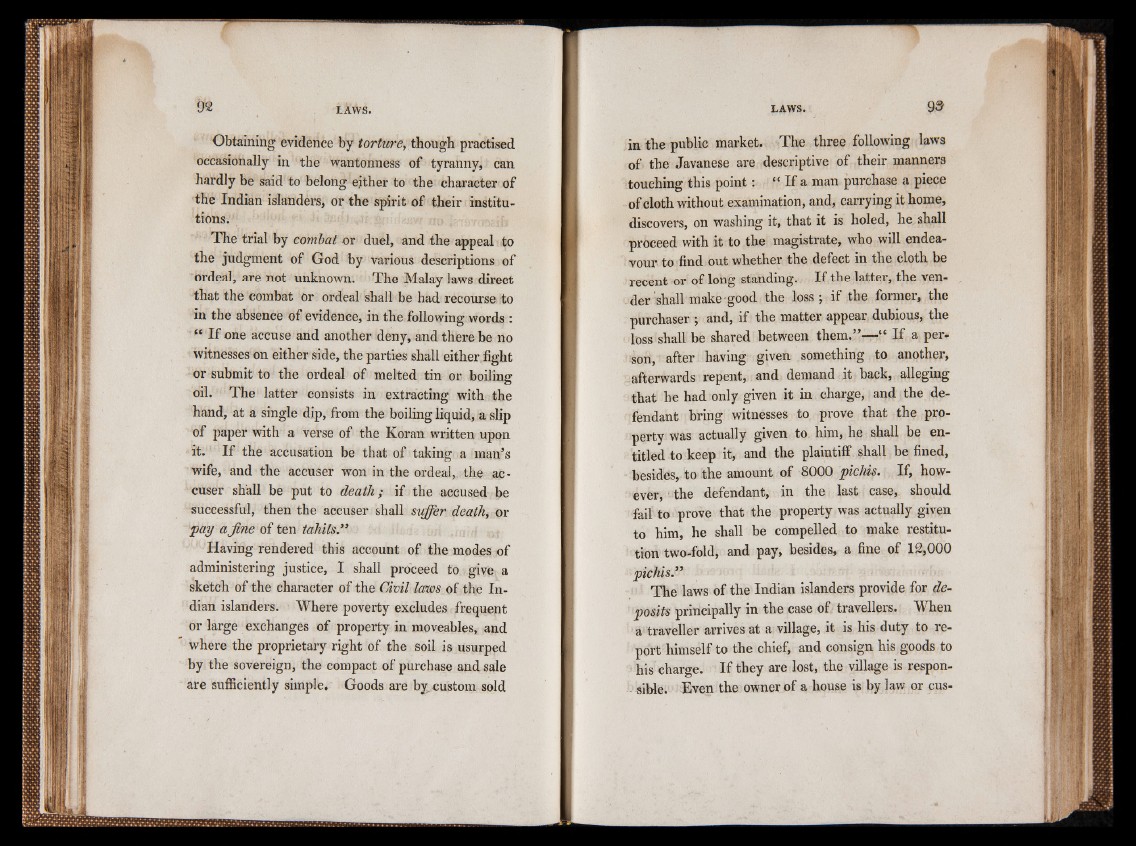

Obtaining evidence by torture, though, practised

occasionally in the wantonness of tyranny, can

hardly be said to belong either to the character of

the Indian islanders, or the spirit of their institutions.

The trial by combat or duel, and the appeal to

the judgment of God by various descriptions of

ordeal, are not unknown. The Malay laws direct

that the combat or ordeal shall be had recourse to

in the absence of evidence, in the following words :

“ If one accuse and another deny, and there be no

witnesses on either side, the parties shall either fight

or submit to the ordeal of melted tin or boiling

oil. The latter consists in extracting with the

hand, at a single dip, from the boiling liquid, a slip

of paper with a verse of the Koran written upon

it. ' If the accusation be that of taking a man’s

wife, and the accuser won in the ordeal, the accuser

shall be put to death; if the accused be

successful, then the accuser shall suffer death, or

pay a fine of ten tahils.,>

Having rendered this account of the modes of

administering justice, I shall proceed to give a

sketch of the character of the Civil laws of the Indian

islanders. Where poverty excludes frequent

or large exchanges of property in moveables, and

where the proprietary right of the soil is usurped

by the sovereign, the compact of purchase and sale

are sufficiently simple. Goods are by custom sold

in the public market. The three following laws

of the Javanese are descriptive of their manners

touching this point: “ If a man purchase a piece

of cloth without examination, and, carrying it home,

discovers, on washing it, that it is holed, he shall

proceed with it to the magistrate, who will endeavour

to find out whether the defect in the cloth be

recent or of long standing. If the latter, the vender

shall make-good the loss y if the former, the

purchaser ; and, if the matter appear dubious, the

loss shall be shared between them.”—“ If a person,

after having given something to another,

afterwards repent, and demand it back, alleging

that he had only given it in charge, and the defendant

bring witnesses to prove that the property

was actually given to him, he shall be entitled

to keep it, and the plaintiff shall be fined,

besides, to the amount of 8000 pichis. If, however,

’ the defendant, m the last case, should

fail to prove that the property was actually given

to him, he shall be compelled to make restitution

two-fold, and pay, besides, a fine of 12,000

pichis.”

The laws of the Indian islanders provide for deposits

principally in the case of travellers. When

a traveller arrives at a village, it is his duty to report

himself to the chief, and consign his goods to

his charge. If they are lost, the village is responsible.

Even the owner of a house is by law or cus