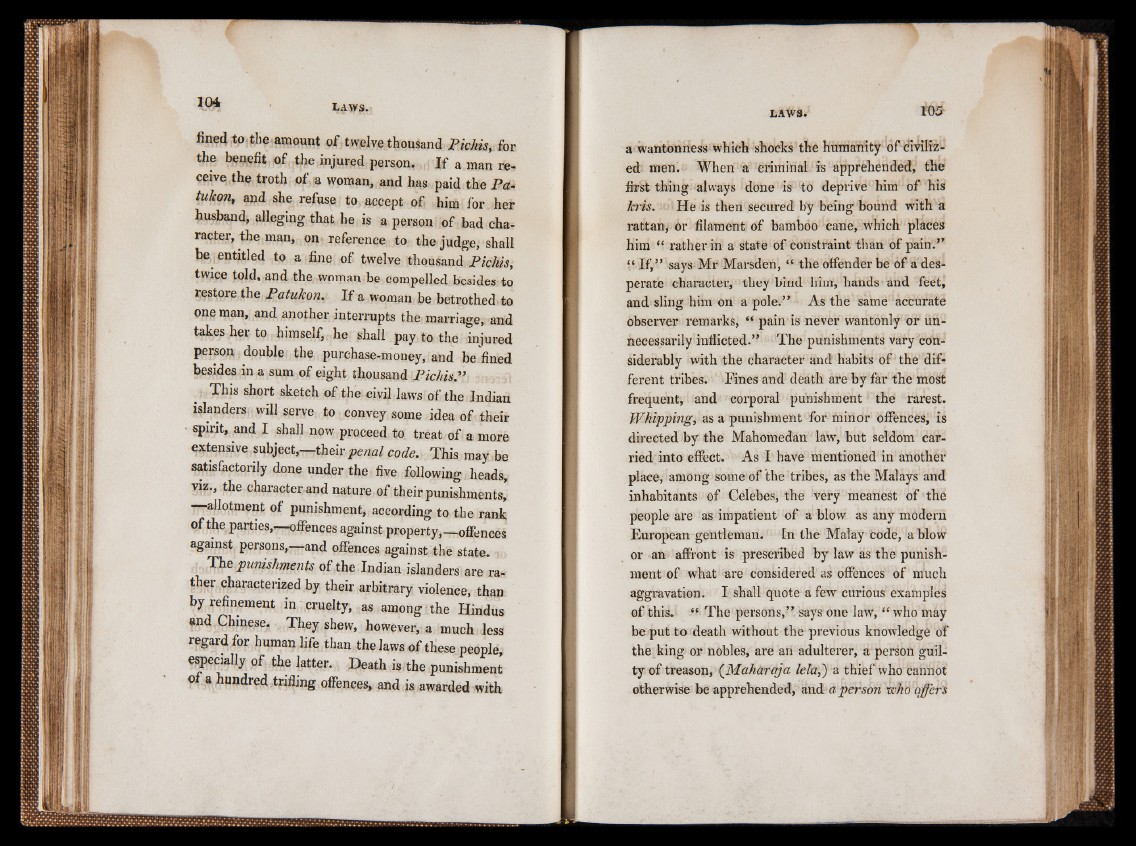

fined to the amount of twelve thousand Pichis, for

the benefit of the injured person. If a man receive

the troth of a woman, and has paid the Pa-

tukon> and she refuse to accept of him for her

husband, alleging that he is a person of bad character,

the man, on reference to the judge, shall

he entitled to a fine of twelve thousand Pichis,

twice told, and the woman be compelled besides to

restore the Patukon. If a woman be betrothed to

one man, and another interrupts the marriage, and

takes her to himself, he shall pay to the injured

person double the purchase-money, and be fined

besides in a sum of eight thousand Pichis.”

:This short sketch of the civil laws of the Indian

islanders will serve, to convey some idea of their

spirit, and I shall now proceed to treat of a more

extensive subject,—their penal code. This may be

satisfactorily done under the five following heads,

viz., the character and nature of their punishments,

—allotment of punishment, according to the rank

of the parties,—offences against property,—offences

against persons,—-and offences against the state. <

The punishments of the Indian islanders are racier

characterized by their arbitrary violence, than

by refinement in cruelty, as among the Hindus

and Chinese. They shew, however, a much less

regard for human life than the laws of these people,

especially of the latter. Death is the punishment

of a hundred ,trifling offences, and is awarded with

a wantonness which shocks the humanity of civilized

men. When a criminal is apprehended, the

first thing always done is to deprive him of his

Icris. He is then secured by being bound with a

rattan, or filament of bamboo cane, which places

him “ rather in a state of constraint than of pain.’’

“ If,” says Mr Marsden, “ the offender be of a desperate

character, they bind him, hands and feet,

and sling him on a pole.” As the same accurate

observer remarks, “ pain is never wantonly or unnecessarily

inflicted.” The punishments vary considerably

with the character and habits of the different

tribes. Fines and death are by far the most

frequent, and corporal punishment the rarest.

Whipping, as a punishment for minor offences, is

directed by the Mahomedan law, but seldom carried

into effect. As I have mentioned in another

place, among some of the tribes, as the Malays and

inhabitants of Celebes, the very meanest of the

people are as impatient of a blow as any modern

European gentleman. In the Malay Code, a blow

or an affront is prescribed by law as the punishment

of what are considered as offences of much

aggravation. I shall quote a few curious examples

of this. U The persons,” says one law, “ who may

be put to death without the previous knowledge of

the king or nobles, are an adulterer, a person guilty

of treason, (Maharaja lela,') a thief who cannot

otherwise be apprehended, and a person who offers