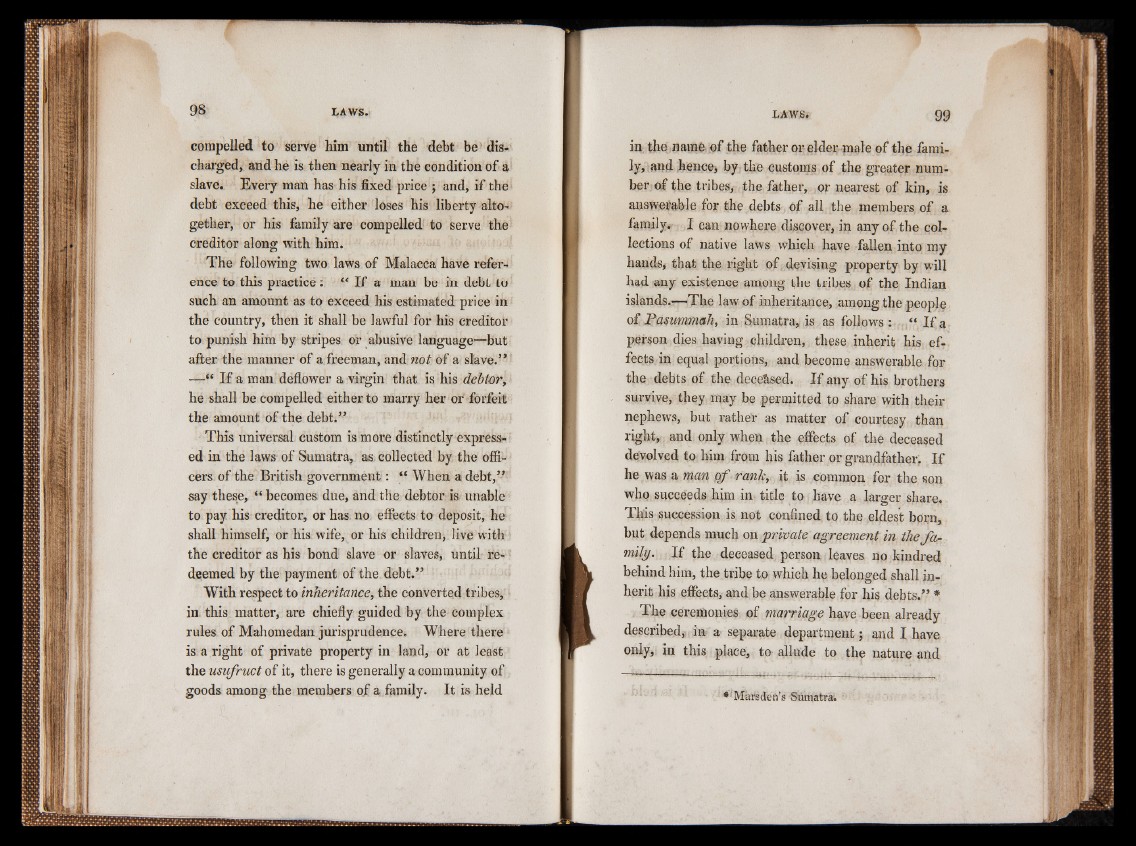

compelled to serve him until the debt be discharged,

and he is then nearly in the condition of a

slave. Every man has his fixed price ; and, if the

debt exceed this, he either loses his liberty altogether,

or his family are compelled to serve the

creditor along with him.

The following two laws of Malacca have reference

to this practice: “ If a man be in debt to

such an amount as to exceed his estimated price in

the country, then it shall be lawful for his creditor

to punish him by stripes or abusive language—but

after the manner of a freeman, and not of a slave.”

—“ If a man deflower a virgin that is his debtor,

he shall be compelled either to marry her or forfeit

the amount of the debt.”

This universal custom is more distinctly expressed

in the laws of Sumatra, as collected by the officers.

of the British government: “ When a debt,”

say these, “ becomes due, and the debtor is unable

to pay his creditor, or has no effects to deposit, he

shall himself, or his wife, or his children, live with

the creditor as his bond slave or slaves, until redeemed

by the payment of the debt.”

With respect to inheritance, the converted tribes,

in this matter, are chiefly guided by the complex

rules of Mahomedan jurisprudence. Where there

is a right of private property in land, or at least

the usufruct of it, there is generally a community of

goods among the members of a family. It is held

in the name of the father or elder male of the family,

and hence, by the customs of the greater number

of the tribes, the father, or nearest of kin, is

answerable for the debts of all the members of a

family. I can nowhere discover, in any of the collections

of native laws which have fallen into my

hands, that the right of devising property by will

had any existence among the tribes of the Indian

islands.—The law of inheritance, among the people

of Pasummak, in Sumatra, is as follows : , If a

person dies having children,, these inherit his effects

in equal portions, and become answerable for

the debts of the deceased. If any of his brothers

survive, they may be permitted to share with their

nephews, but rather as matter of courtesy than

right, and only when the effects of the deceased

devolved to him from his father or grandfather. If

he was a man of rank, it is common for the son

who succeeds him in title to have a larger share.

Tftis succession is not confined to the eldest born,

but depends much on private agreement in thefa~

mill/. If the deceased person leaves no kindred

behind him, the tribe to which he belonged shall inherit

his effects, and be answerable for his debts.’’ *

The ceremonies of marriage have been already

described, in a separate department; and I have

only, in this place, to allude to the nature and

*' Marsden’s Sumatra'.