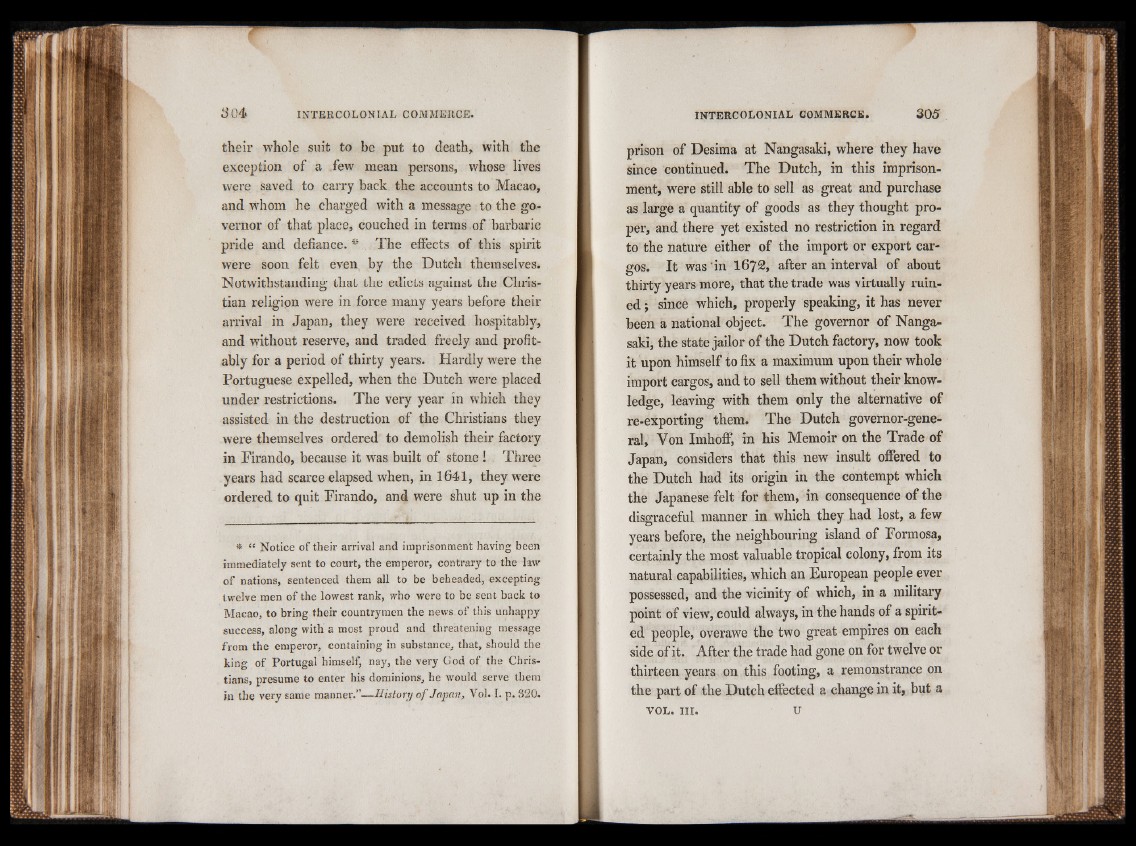

their whole suit to be put to death, with the

exception of a few mean persons, whose lives

were saved to earry back the accounts to Macao,

and whom he charged with a message to the governor

of that place, couched in terms of barbaric

pride and defiance. * The effects of this spirit

were soon felt even by the Dutch themselves.

Notwithstanding that the edicts against the Christian

religion were in force many years before their

arrival in Japan, they were received hospitably,

and without reserve, and traded freely and profitably

for a period of thirty years. Hardly were the

Portuguese expelled, when the Dutch were placed

under restrictions. The very year in which they

assisted in the destruction of the Christians they

were themselves ordered to demolish their factory

in Firando, because it was built of stone ! Three

years had scarce elapsed when, in 1641, they were

ordered to quit Firando, and were shut up in the

* “ Notice of their arrival and imprisonment having been

immediately sent to court, the emperor, contrary to the law

of nations, sentenced them all to be beheaded, excepting

twelve men of the lowest rank, who were to be sent back to

Macao, to bring their countrymen the news of this unhappy

success, along with a most proud and threatening message

from the emperor, containing in substance, that, should the

king of Portugal himself, nay, the very God of the Christians,

presume to enter his dominions, he would serve them

in the very same manner.”—History of Japan, Vol. I. p. 320.

prison of Desima at Nangasaki, where they have

since continued. The Dutch, in this imprisonment,

were still able to sell as great and purchase

as large a quantity of goods as they thought proper,

and there yet existed no restriction in regard

to the nature either of the import or export cargos.

It was 'in 1672, after an interval of about

thirty years more, that the trade was virtually ruined

; since which, properly speaking, it has never

been a national object. The governor of Nangasaki,

the state jailor of the Dutch factory, now took

it upon himself to fix a maximum upon their whole

import cargos, and to sell them without their knowledge,

leaving with them only the alternative of

re-exporting them. The Dutch governor-general,

Yon Imhoff, in his Memoir on the Trade of

Japan, considers that this new insult offered to

the Dutch had its origin in the contempt which

the Japanese felt for them, in consequence of the

disgraceful manner in which they had lost, a few

years before, the neighbouring island of Formosa,

certainly the most valuable tropical colony, from its

natural capabilities, which an European people ever

possessed, and the vicinity of which, in a military

point of view, could always, in the hands of a spirited

people, overawe the two great empires on each

side of it. After the trade had gone on for twelve or

thirteen years on this footing, a remonstrance on

the part of the Dutch effected a change in it, but a

v o l . i n . u