In countries upon the equator, on the other hand,

it is an object of comfort throughout the year,—

from the frequency of rains,—on account of the land

and sea breezes,—and of the prevalence of elevated

tracts of land. During the summer of countries

near the tropics, European habits give way to the

climate, and cotton garments are the constant wear

of the colonists, but at the equator the principal portion

of dress with them is always woollen cloth. To

the feelings of the natives, who are naturally less oppressed

with the heats than Europeans, woollens

are objects of still more comfort; and the consumption

of them is commensurate with their means of

obtaining them.

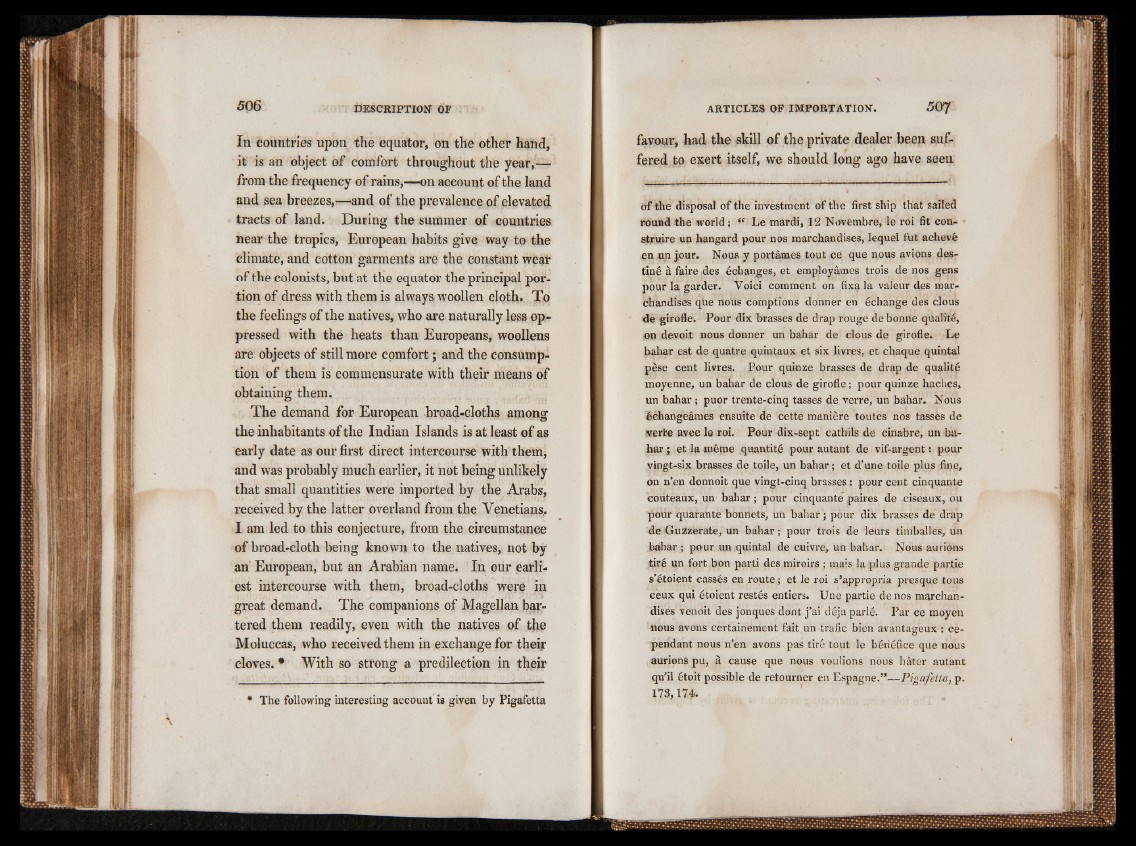

The demand for European broad-cloths among

the inhabitants of the Indian Islands is at least of as

early date as our first direct intercourse with them,

and was probably much earlier, it not being unlikely

that small quantities were imported by the Arabs,

received by the latter overland from the Venetians,

I am led to this conjecture, from the circumstance

of broad-cloth being known to the natives, not by

an European, but an Arabian name. In our earliest

intercourse with them, broad-cloths were in

great demand. The companions of Magellan bartered

them readily, even with the natives of the

Moluccas, who received them in exchange for their

cloves. * With so strong a predilection in their

* The following interesting account is given by Pigafetta

favour, had the skill of the private dealer been suffered

to exert itself, we should long ago have seen

of the disposai of the investment of the first ship that sailed

round the world; “ Le mardi, 12 Novembre, le roi fit construire

un hangard pour nos marchandises, lequel fut achevé

en un jour. Nous y portâmes tout ce que nous avions destiné

à faire des échanges, et employâmes trois de nos gens

pour la garder. Voici comment on fixa la valeur des marchandises

que nous comptions donner en échange des clous

de girofle. Pour dix brasses de drap rouge de bonrte qualité,

on devoit nous donner un bahar de clous de girofle. Le

bahar est de quatre quintaux et six livres, et chaque quintal

pèse cent livres. Pour quinze brasses de drap de qualité

moyenne, un bahar de clous de girofle ; pour quinze haches,

un bahar ; puor trente-cinq tasses de verre, un bahar. Nous

échangeâmes ensuite de cette manière toutes nos tasses de

verte avec le roi. Pour dix-sept cathils de cinabre, un bahar

; et la même quantité pour autant de vif-argent : pour

vingt-six brasses de toile, un bahar ; et d’une toile plus fine,

on n’en donnoit que vingt-cinq brasses : pour cent cinquante

couteaux, un bahar; pour cinquante paires de ciseaux, ou

pour quarante bonnets, un bahar ; pour dix brasses de drap

de Guzzerate, un bahar ; pour trois de leurs timballes, un

bahar; pour un quintal de cuivre, un bahar. Nous aurions

tiré un fort bon parti des miroirs ; mais la plus grande partie

s’étoient cassés en route ; et le roi s’appropria presque tous

ceux qui étoient restés entiers. Une partie de nos marchandises

venoit des jonques dont j’ai déjà parlé. Par ce moyen

nous avons certainement fait un trafic bien avantageux : cependant

nous n’en avons pas tiré tout le bénéfice que nous

aurions pu, à cause que nous voulions nous hâter autant

qu’il étoit possible de retourner en Espagne.”— Pigafetta, p.

173,174.