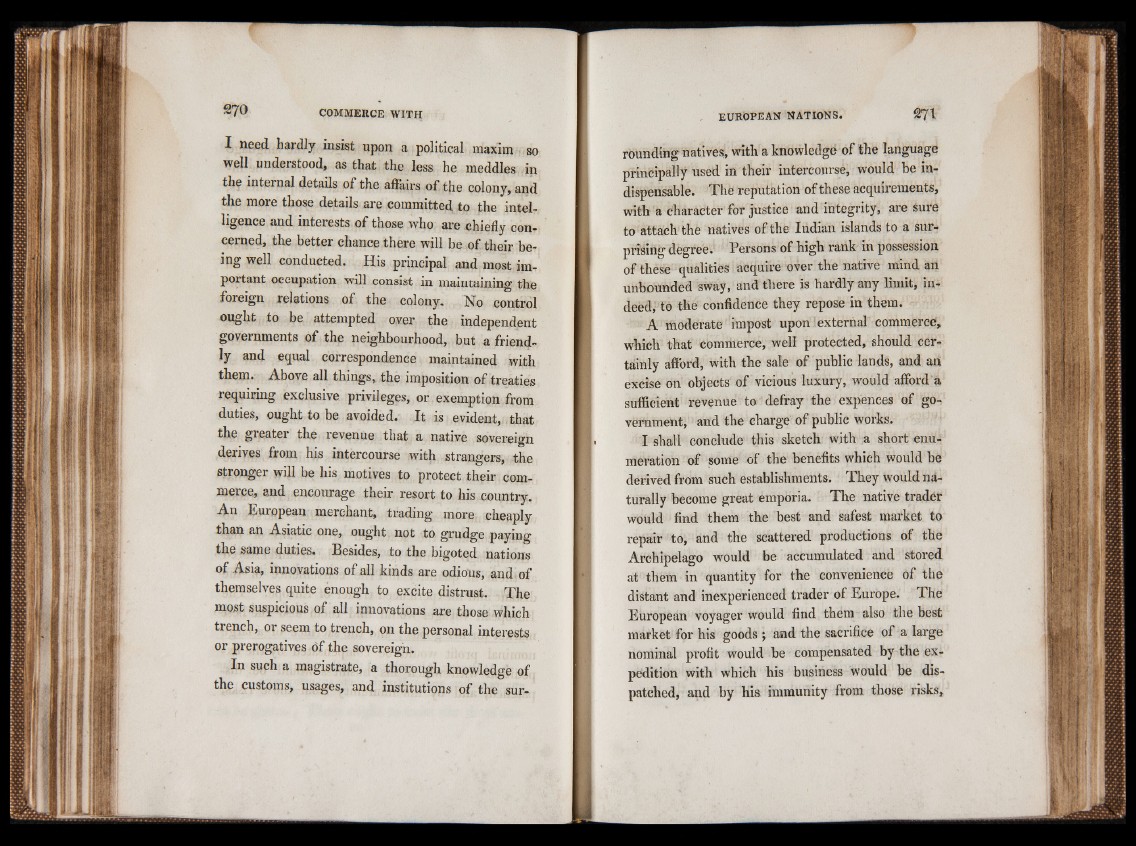

I need hardly insist upon a political maxim so

well understood, as that the less he meddles in

the internal details of the affairs of the colony, and

the more those details are committed to the intelligence

and interests of those who are chiefly concerned,

the better chance there will be of their being

well conducted. His principal and most important

occupation will consist in maintaining the

foreign relations of the colony. No control

ought to be attempted over the independent

governments of the neighbourhood, but a friendly

and equal correspondence maintained with

them. Above all things, the imposition of treaties

requiring exclusive privileges, or exemption from

duties, ought to be avoided. It is evident, that

the greater the revenue that a native sovereign

derives from his intercourse with strangers, the

stronger will be his motives to protect their commerce,

and encourage their resort to his country.

An European merchant, trading more cheaply

than an Asiatic one, ought not to grudge paying

the same duties. Besides, to the bigoted nations

of Asia, innovations of all kinds are odious, and : of

themselves quite enough to excite distrust. The

most suspicious of all innovations are those which

trench, or seem to trench, on the personal interests

or prerogatives of the sovereign.

In such a magistrate, a thorough knowledge of

the customs, usages, and institutions of the surrounding

natives, with a knowledge of the language

principally used in their intercourse, would be indispensable.

The reputation of these acquirements,

with a character for justice and integrity, are sure

to attach the natives of the Indian islands to a surprising

degree. Persons of high rank in possession

of these qualities acquire over the native mind an

unbounded sway, and there is hardly any limit, indeed,

to the confidence they repose in them.

A moderate impost upon’external commerce,

which that commerce, well protected, should certainly

afford, with the sale of public lands, and an

excise on objects of vicious luxury, would afford a

sufficient revenue to defray the expences of government,

and the charge of public works.

I shall conclude this sketch with a short enumeration

of some of the benefits which would be

derived from such establishments. They would naturally

become great emporia. The native trader

would find them the best and safest market to

repair to, and the scattered productions of the

Archipelago would be accumulated and stored

at them in quantity for the convenience of the

distant and inexperienced trader of Europe. The

European voyager would find them also the best

market for his goods; and the sacrifice of a large

nominal profit would be compensated by the expedition

with which his business would be dispatched,

and by his immunity from those risks*