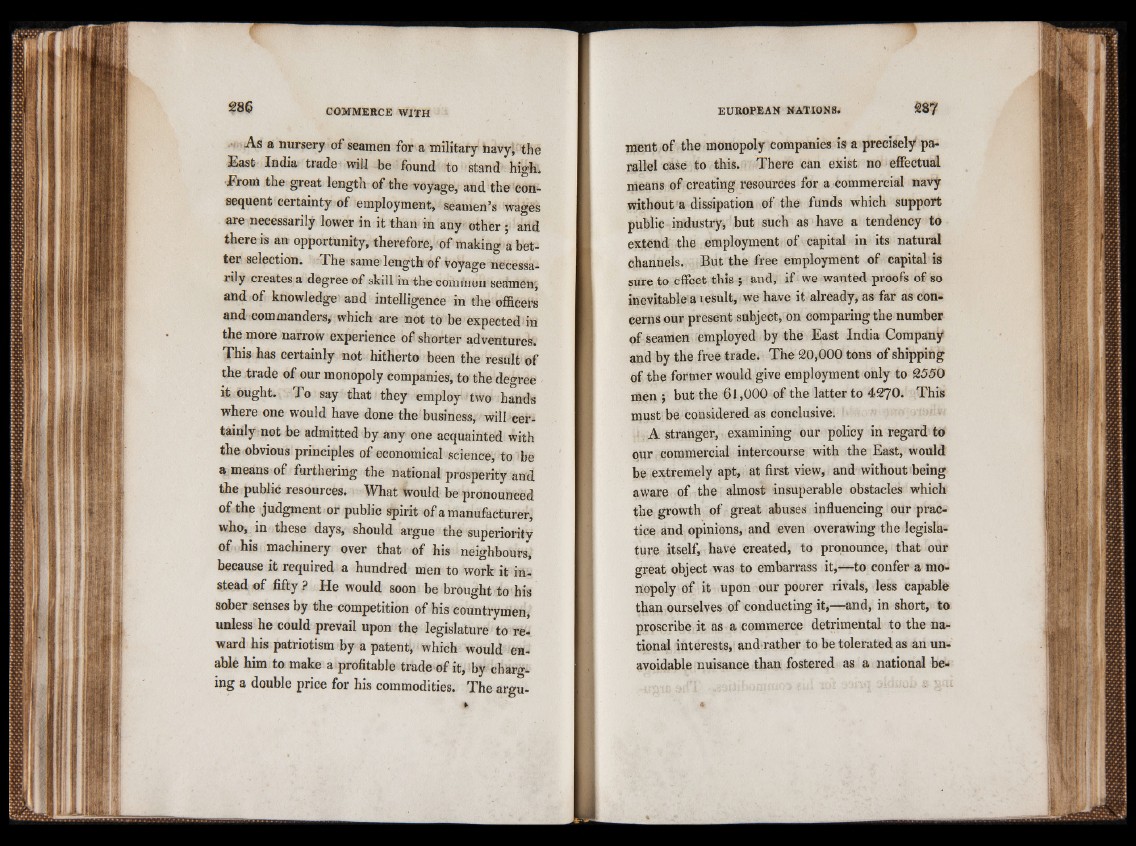

- As a nursery of seamen for a military navy/the

East India trade will be found to stand high,

from the great length of the voyage, and thecon-

sequent certainty of employment, seamen,s wages

are necessarily lower in it than in any other ; and

there is an opportunity, therefore, of making a better

selection. The same length of voyage necessarily

creates a degree of skill in the common seamen,

and of knowledge and intelligence in the officers

and commanders, which are not to be expected in

the more narrow experience of shorter adventures.

This has certainly not hitherto been the result of

the trade of our monopoly companies, to the degree

it ought. To say that they employ two hands

where one would have done the business, will certainly

not be admitted by any one acquainted with

the obvious principles of economical science, to be

a means of furthering the national prosperity and

the public resources. What Would be pronounced

of the judgment or public spirit of a manufacturer*

who, in these days,' should argue the superiority

of his machinery over that of his neighbours/

because it required a hundred men to work it instead

of fifty ? He would soon be brought to his

sober senses by the competition of his countrymen,

unless he could prevail upon the legislature to reward

his patriotism by a patent, which would enable

him to make a profitable trade of it, by charging

a double price for his commodities. The argumerit

of the monopoly companies is a precisely parallel

case to this. There can exist no effectual

means of creating resources for a commercial navy

without a dissipation of the funds which support

public industry, but such as have a tendency to

extend the employment of capital in its natural

channels. But the free employment of capital is

sure to effect this ; and, if we wanted proofs of so

inevitable a result, we have it already, as far as concerns

our present subject, on comparing the number

of seamen employed by the East India Company

and by the free trade. The 20,000 tons of shipping

of the former would give employment only to £550

men ; but the 61,000 of the latter to 4270. This

must be considered as conclusive.

A stranger, examining our policy in regard to

our commercial intercourse with the East, would

be extremely apt, at first view, and without being

aware of the almost insuperable obstacles which

the growth of great abuses influencing our practice

and opinions, and even overawing the legislature

itself, have created, to pronounce, that our

great object was to embarrass it,—to confer a monopoly

of it upon our poorer rivals, less capable

than ourselves of conducting it,—and, in short, to

proscribe it as a commerce detrimental to the national

interests, and rather to be tolerated as an unavoidable

nuisance than fostered as a national be