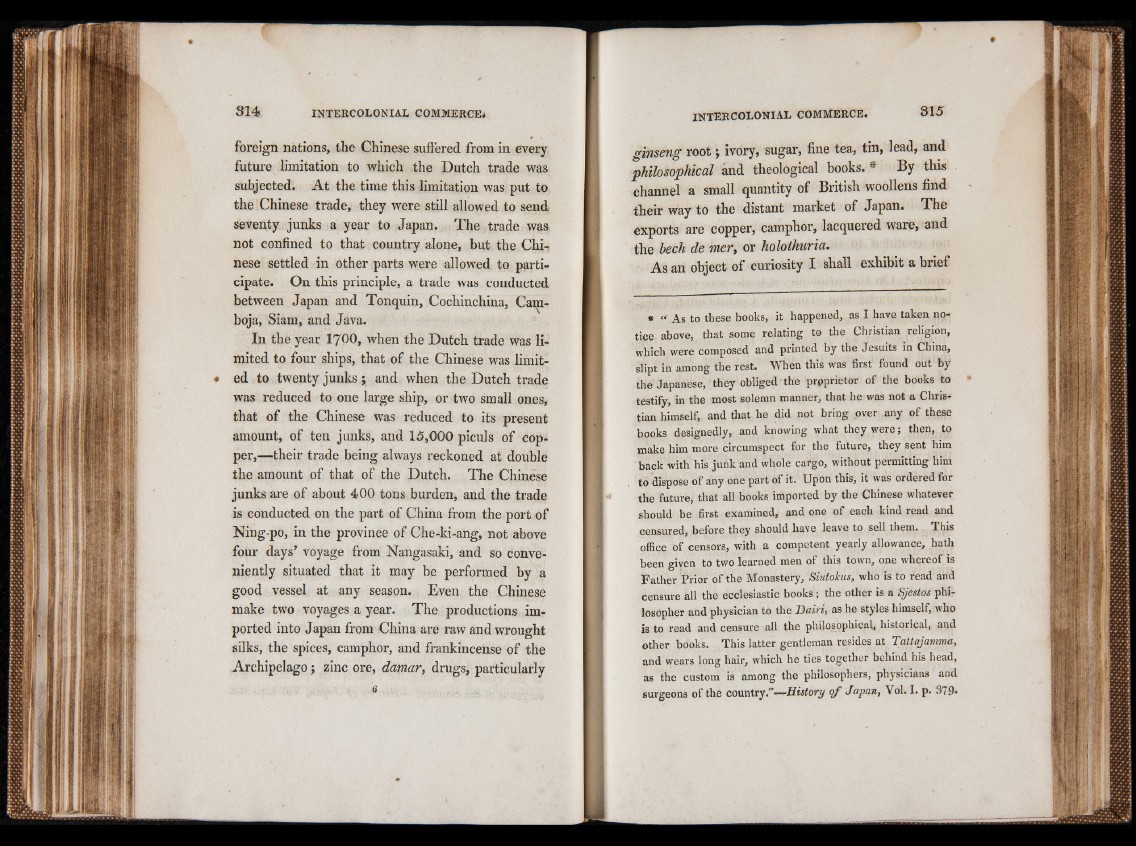

foreign nations, the Chinese suffered from in every

future limitation to which the Dutch trade was

subjected. At the time this limitation was put to

the Chinese trade, they were still allowed to send

seventy junks a year to Japan. The trade was

not confined to that country alone, but the Chinese

settled in other parts were allowed to participate.

On this principle, a trade was conducted

between Japan and Tonquin, Cochinchina, Cam-

boja, Siam, and Java.

In the year 1700, when the Dutch trade was limited

to four ships, that of the Chinese was limited

to twenty junks ; and when the Dutch trade

was reduced to one large ship, or two small ones,

that of the Chinese was reduced to its present

amount, of ten junks, and 15,000 piculs of copper,—

their trade being always reckoned at double

the amount of that of the Dutch. The Chinese

junks are of about 400 tons burden, and the trade

is conducted on the part of China from the port of

Ning-po, in the province of Che-ki-ang, not above

four days’ voyage from Nangasaki, and so conveniently

situated that it may be performed by a

good vessel at any season. Even the Chinese

make two voyages a year. The productions imported

into Japan from China are raw and wrought

silks, the spices, camphor, and frankincense of the

Archipelago; zinc ore, damar, drugs, particularly

ginseng root; ivory, sugar, fine tea, tin, lead, and

philosophical and theological books. * By this

channel a small quantity of British woollens find

their way to the distant market of Japan. The

exports are copper, camphor, lacquered ware, and

the bech de mer, or holothuria.

As an object of curiosity I shall exhibit a brief

* “ As to these books, it happened, as I have taken notice

above, that some relating to the Christian religion,

which were composed and printed by the Jesuits in China,

slipt in among the rest. When this was first found out by

the Japanese, they obliged the prpprietor of the books to

testify, in the most solemn manner, that he was not a Christian

himself, and that he did not bring over any of these

books designedly, and knowing what they were; then, to

make him more circumspect for the future, they sent him

back with his junk and whole cargo, without permitting him

to dispose of any one part of it. Upon this, it was ordered for

the future, that all books imported by the Chinese whatever

should be first examined, and one of each kind read and

censured, before they should have leave to sell them. This

office of censors, with a competent yearly allowance, hath

been given to two learned men of this town, one whereof is

Father Prior of the Monastery, Siutolcus, who is to read and

censure all the ecclesiastic books; the other is a Sjestos philosopher

and physician to the Bairi, as he styles himself, who

is to read and censure all the philosophical, historical, and

other books. This latter gentleman resides at TattajamTna,

and wears long hair, which he ties together behind his head,

as the custom is among the philosophers, physicians and

surgeons of the country.”—History q f Japan, Vol. I. p. 379*