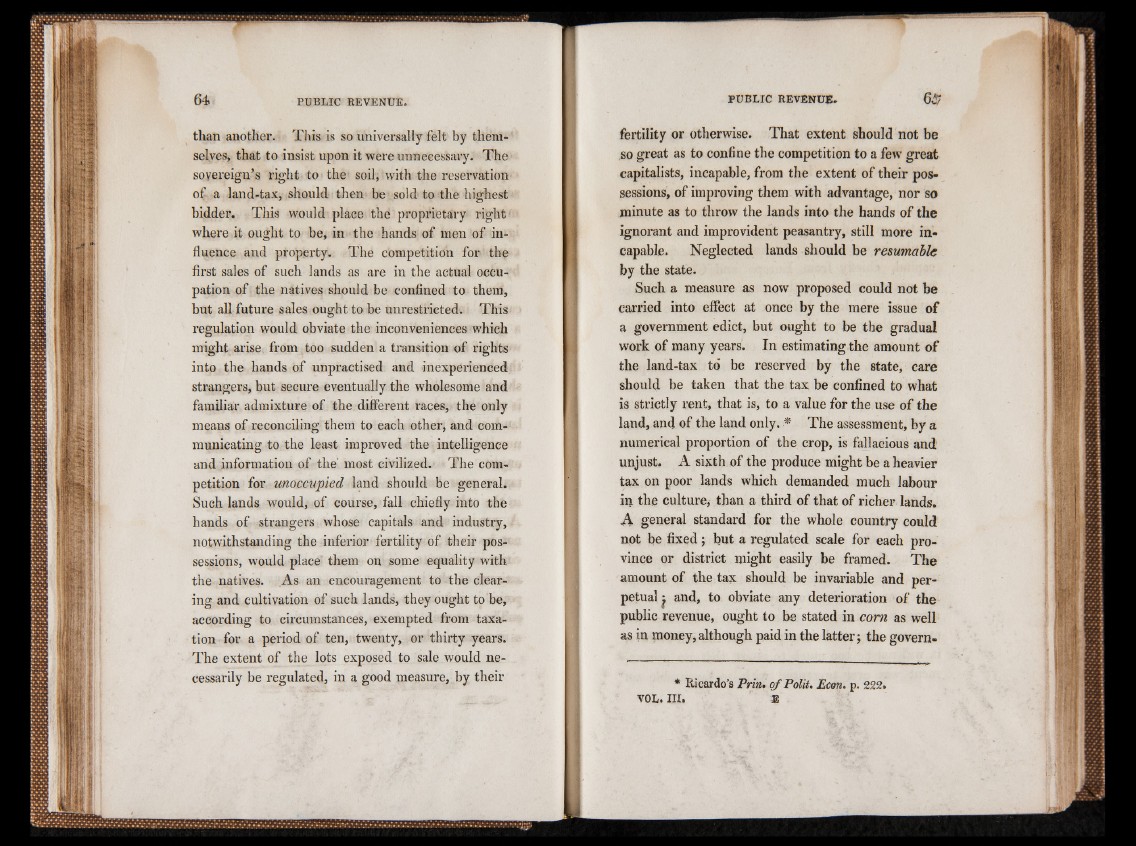

than another. This is so universally felt by themselves,

that to insist upon it were unnecessary. The

sovereign’s right to the soil, with the reservation

of a land-tax, should then be sold to the highest

bidder. This would place the proprietary right

where it ought to be, in the hands of men of influence

and property. The competition for the

first sales of such lands as are in the actual occupation

of the natives should be confined to them,

but all future sales ought to be unrestricted. This

regulation would obviate the inconveniences which

might arise from too sudden a transition of rights

into the hands of unpractised and inexperienced

strangers, but secure eventually the wholesome and

familiar admixture of the different races, the only

means of reconciling them to each other, and communicating

to the least improved the intelligence

and information of the' most civilized. The competition

for unoccupied land should be general.

Such lands would, of course, fall chiefly into the

hands of strangers whose capitals and industry,

notwithstanding the inferior fertility of their possessions,

would place them on some equality with

the natives. As an encouragement to the clearing

and cultivation of such lands, they ought to be,

according to circumstances, exempted from taxation

for a period of ten, twenty, or thirty years.

The extent of the lots exposed to sale would necessarily

be regulated, in a good measure, by their

fertility or otherwise. That extent should not be

so great as to confine the competition to a few great

capitalists, incapable, from the extent of their possessions,

of improving them with advantage, nor so

minute as to throw the lands into the hands of the

ignorant and improvident peasantry, still more incapable.

Neglected lands should be resumable

by the state.

Such a measure as now proposed could not be

carried into effect at once by the mere issue of

a government edict, but ought to be the gradual

work of many years. In estimating the amount of

the land-tax to be reserved by the state, care

should be taken that the tax be confined to what

is strictly rent, that is, to a value for the use of the

land, and of the land only. * The assessment, by a

numerical proportion of the crop, is fallacious and

unjust, A sixth of the produce might be a heavier

tax on poor lands which demanded much labour

in the culture* than a third of that of richer lands.

A general standard for the whole country could

not be fixed; but a regulated scale for each province

or district might easily be framed. The

amount of the tax should be invariable and perpetual

: and, to obviate any deterioration of the

public revenue, ought to be stated in corn as well

as in money, although paid in the latter j the govern*

Ricardo’s Prin* of Polit. Econ. p. 222.

VOL. III. £