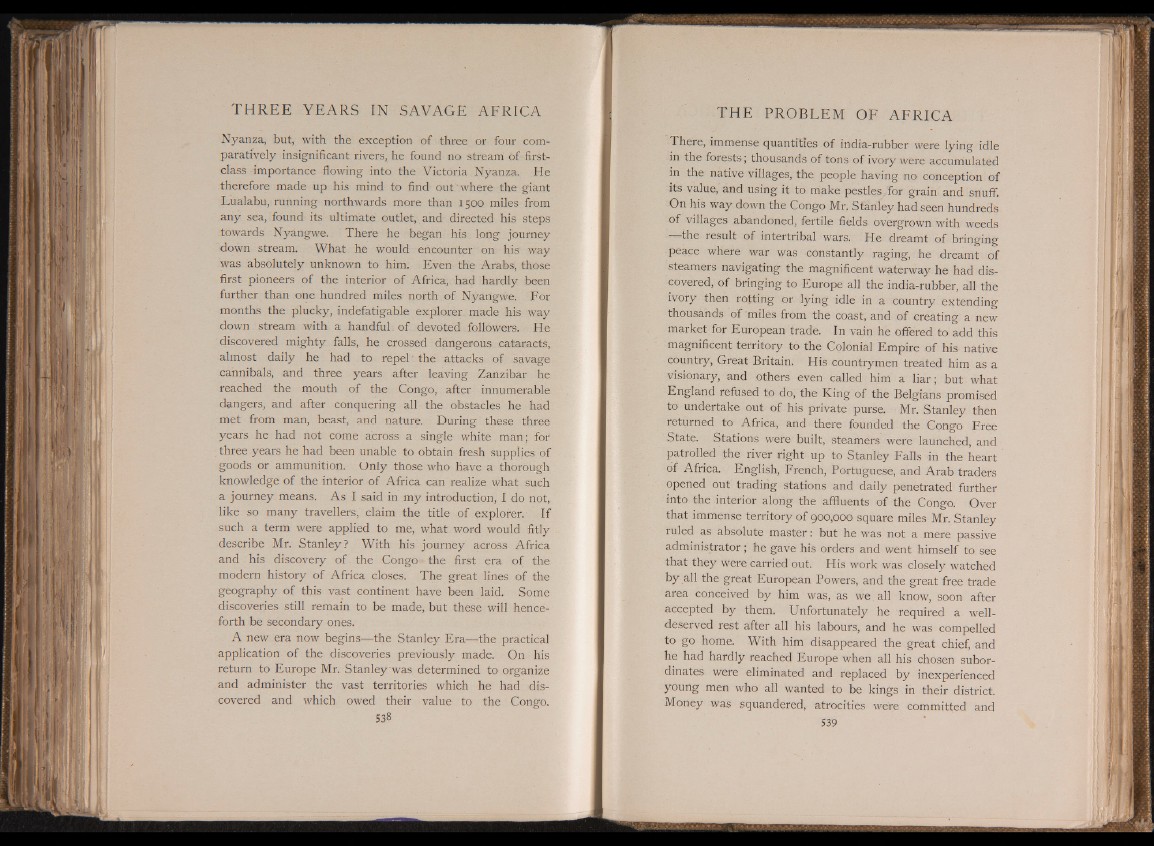

Nyanza, but, with the exception of three or four comparatively

insignificant rivers, he found no stream of first-

class-importance flowing into the Victoria Nyanza. He

therefore made up his mind to find out where the giant

Lualabu, running northwards more than 1500 miles from

any sea, found its ultimate outlet, and directed his steps

towards Nyangwe. There he began his long journey

down stream. What he would encounter on his way

was absolutely unknown to him. Even the Arabs, those

first pioneers of the interior of Africa, had hardly been

further than one hundred miles north of Nyangwe. For

months the plucky, indefatigable explorer made his way

down stream with a handful of devoted followers. He

discovered mighty falls, he crossed dangerous cataracts,

almost daily he had to repel the attacks of savage

cannibals, and three years after leaving Zanzibar he

reached the mouth of the Congo, after innumerable

dangers, and after conquering all the obstacles he had

met from man, beast, and nature. During these three

years he had not come across a single white man; for

three years he had been unable to obtain fresh supplies of

goods or ammunition. Only those who have a thorough

knowledge of the interior of Africa can realize what such

a journey means. As I said in my introduction, I do not,

like so many travellers, claim the title of explorer. If

such a term were applied to me, what word would fitly

describe Mr. Stanley? With his journey across Africa

and his discovery of the Congo the first era of the

modern history of Africa closes. The great lines of the

geography of this vast continent have been laid. Some

discoveries still remain to be made, but these will henceforth

be secondary ones.

A new era now begins—the Stanley Era—the practical

application of the discoveries previously made. On his

return to Europe Mr. Stanley was determined to organize

and administer the vast territories which he had discovered

and which owed their value to the Congo.

538

There, immense quantities of india-rubber were lying idle

in the forests, thousands of tons of ivory were accumulated

in the native villages, the people having no conception of

its value, and using it to make pestles for grain and snuff.

On his way down the Congo Mr. Stanley had seen hundreds

of villages abandoned, fertile fields overgrown with weeds

—the result of intertribal wars. He dreamt of bringing

peace where war was constantly raging, he dreamt of

steamers navigating the magnificent waterway he had discovered,

of bringing to Europe all the india-rubber, all the

ivory then rotting or lying idle in a country extending

thousands of miles from the coast, and of creating a new

market for European trade. In vain he offered to add this

magnificent territory to the Colonial Empire of his native

country, Great Britain. His countrymen treated him as a

visionary, and others even called him a liar; but what

England refused to do, the King of the Belgians promised

to undertake out of his private purse. Mr. Stanley then

returned to Africa, and there founded the Congo Free

State. Stations were built, steamers were launched, and

patrolled the river right up to Stanley Falls in the heart

of Africa. English, French, Portuguese, and Arab traders

opened out trading stations and daily penetrated further

into the interior along the affluents of the Congo. Over

that immense territory of 900,000 square miles Mr. Stanley

ruled as absolute master: but he was not a mere passive

administrator; he gave his orders and went himself to see

that they were carried out. His work was closely watched

by all the great European Powers, and the great free trade

area conceived by him was, as we all know, soon after

accepted by them. Unfortunately he required a well-

deserved rest after all his labours, and he was compelled

to go home. With him disappeared the great chief, and

he had hardly reached Europe when all his chosen subordinates

were eliminated and replaced by inexperienced

young men who all wanted to be kings in their district.

Money was squandered, atrocities were committed and

S39