jy&v:

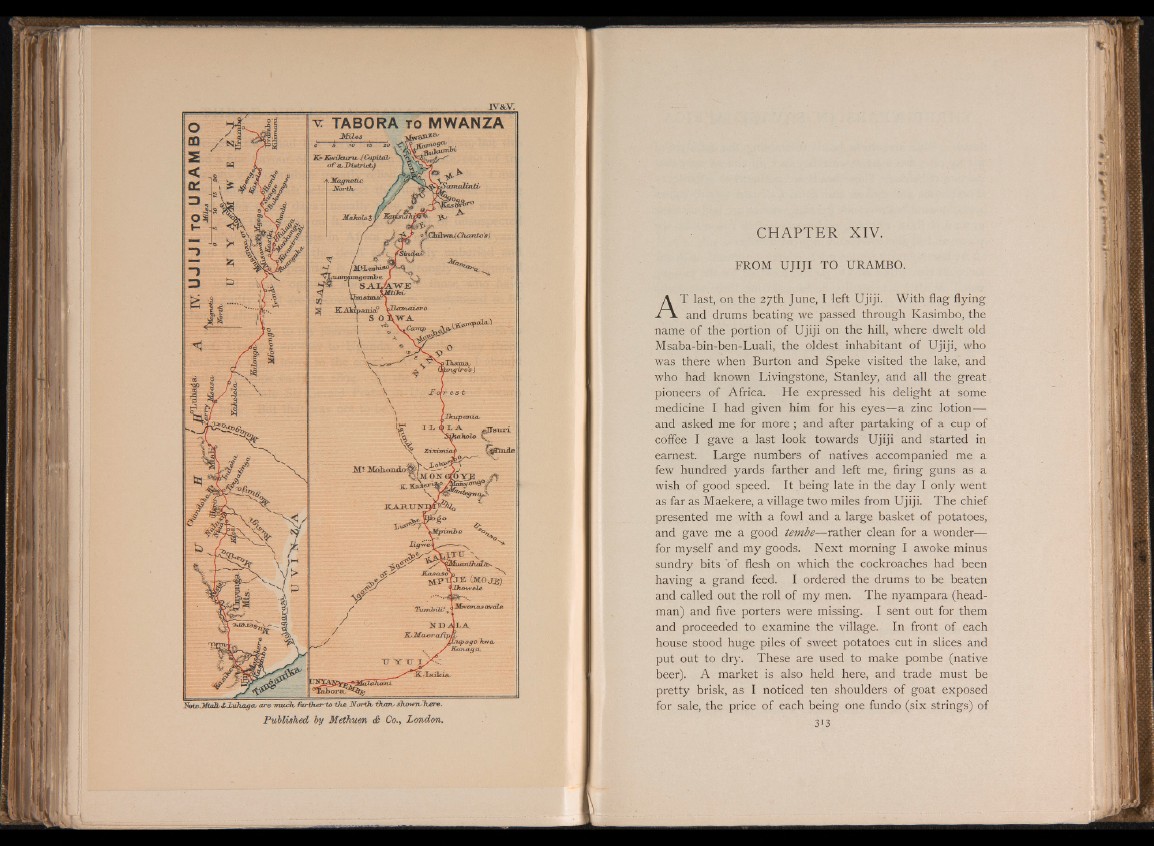

v TABORA to MWANZA Milas

T&Eiw ikiarusjLafitjab

JjQnhva/ Ctuvnto's)

Camp

Thami). fcm^xroisj

MV Moi.ond.o

iifeijTT m m

j^ulsta Ps0'^q3 J® (MOje^) vJJuywele

■■7.i'7x‘* d-Mwaruiaavale

Quupogo k

KcarvagcL

o f a/D istricts

2£akob>ty Xpp*1

(It-Lup cavicL

I I t ®¿¿Ik Aah olo ^€TsTlld.

Turnbili!

N DA LA

T&McueraJrpK,

U x TJ 1 /—.

.IsikieL,

vtt«» WKnde

iT ofceJftflitJrZiuh/ujas are -muck iurOierto Hue North/ thaiu shomuhere.

Published by Methuen & Co., London.

9U9J3

C H A P T E R XIV.

FROM UJIJI TO URAMBO.

A T last, on the 27th June, I left Ujiji. With flag flying

d \ - and drums beating we passed through Kasimbo, the

name of the portion of Ujiji on the hill, where dwelt old

Msaba-bin-ben-Luali, the oldest inhabitant of Ujiji, who

was there when Burton and Speke visited the lake, and

who had known Livingstone, Stanley, and all the great

pioneers of Africa. He expressed his delight at some

medicine I had given him for his eyes—a zinc lotion—

and asked me for more ; and after partaking of a cup of

coffee I gave a last look towards Ujiji and started in

earnest. Large numbers of natives accompanied me a

few hundred yards farther and left me, firing guns as a

wish of good speed. It being late in the day I only went

as far as Maekere, a village two miles from Ujiji. The chief

presented me with a fowl and a large basket of potatoes,

and gave me a good tembe—rather clean for a wonder—

for myself and my goods. Next morning I awoke minus

sundry bits of flesh on which the cockroaches had been

having a grand feed. I ordered the drums to be beaten

and called out the roll of my men. The nyampara (headman)

and five porters were missing. I sent out for them

and proceeded to examine the village. In front of each

house stood huge piles of sweet potatoes cut in slices and

put out to dry. These are used to make pombe (native

beer). A market is also held here, and trade must be

pretty brisk, as I noticed ten shoulders of goat exposed

for sale, the price of each being one fundo (six strings) of