it may be called. Among them, as among most Africans,

the “ musimo,” or spirits of the dead, are the one immaterial

idea which the native mind can grasp. Even this,

however, is only very crudely spiritual, as the fact of

offering a disembodied soul beer shows plainly enough.

They also attribute other evils besides disease to the

spirits of the dead. With this belief in ghosts they

combine- curiously enough the doctrine of metempsychosis,

as do many other tribes. The spirits of the

dead are believed to pass into other animals—men of

rank become hyaenas—but never into men.

Except that a man of these tribes will divide anything

that is given him among all his companions, they

have no idea of morality. I could tell many stories of

all kinds of unnatural and barbarous abominations

among them, and especially among the black Portuguese,

but I do not think there would be any useful

purpose served by their recital.

Industrially, however, these people take a comparatively

high rank among negroes. Of course witchcraft enters

largely into all their operations. When a man intends

to build a house, the inevitable sorcerer is; called in.

He brings- with him some flour and makes a little

heap of it on the ground. If next morning this heap is

undisturbed the site is a good one. If the rats have

eaten it or it has been scattered in any other way, it

would be madness to build in so unpropitious a spot. The

huts are always round, built of wood, and covered with

mud. Poor families live together; the rich have,.as I said

above, a hut for each wife. There are no windows, and the

smoke of the fire escapes through any interstices it can

find. Each hut is surrounded by a fence of reeds, making

a little court four or five yards in extent. One of these

joins , on to another, and as they are all square it is

very difficult, despite the number of little paths, about

a yard wide, to find your way to any particular hut in

a village. The whole village is surrounded by a similar

.236

fence of rushes with several gates. All refuse is carried

outside. In each village there are a scertain number of

enclosures roofed in, containing grindstones for making

flour; the women perform this work all in a body.

They both spin and weave the native cotton, and know

two vegetable dyes, one yellow, the other black, obtained

by soaking the bark of certain trees in hot water. They

make very strong string, both of cotton and of bark

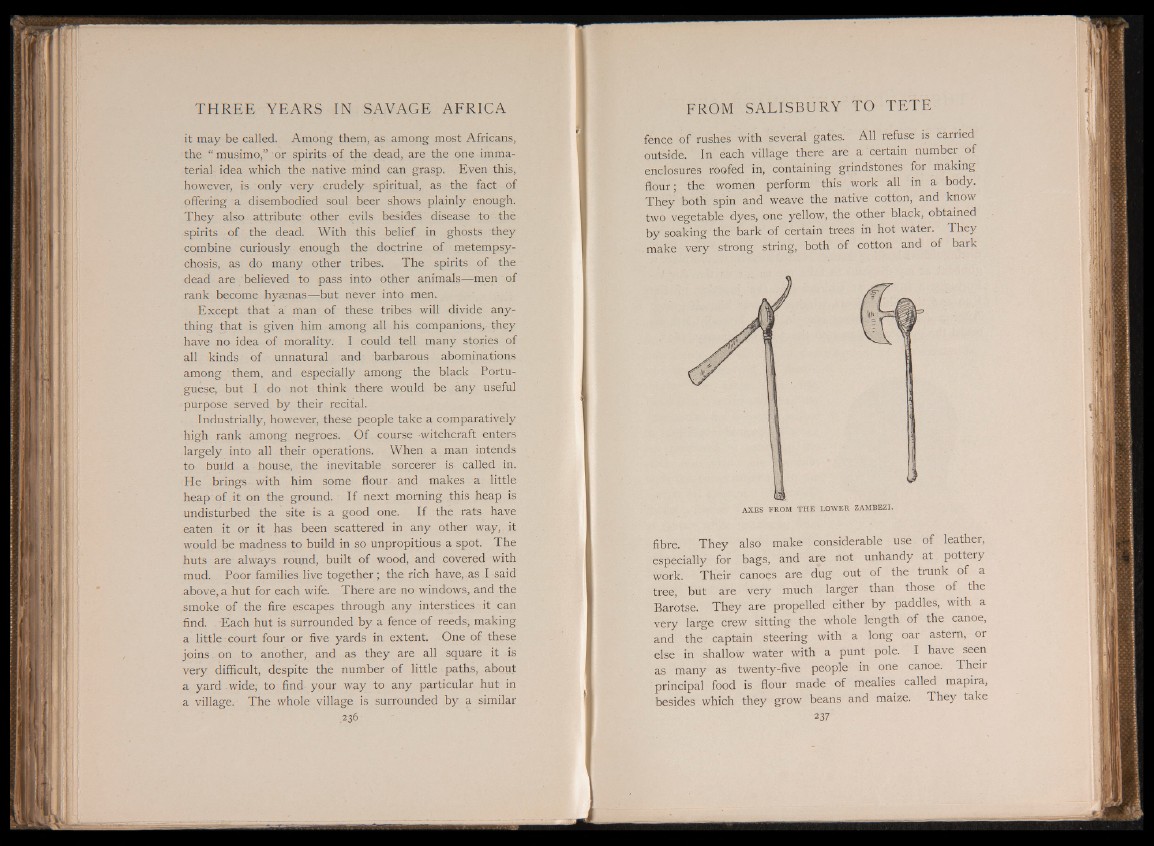

AXES FROM TH E LOWER ZAMBEZI.

fibre. They also make considerable use of leather,

especially for bags, and are not unhandy at pottery

work. Their canoes are dug out of the trunk of a

tree, but are very much larger than those of the

Barotse. They are propelled either by paddles, with a

very large crew sitting the whole length of the canoe,

and the captain steering with a long oar astern, or

else in shallow water with a punt pole. I have seen

as many as twenty-five people in one canoe. Their

principal food is flour made of mealies called mapira,

besides which they grow beans and maize. They take

237