which they add a touch of civilization in the form of

tin ornaments made out of the white man’s discarded

meat tins. The Mashona are by no means without

industry and ingenuity. They grow good crops of

mealies, and some of them are very expert smelters

and ironworkers. They make pottery also with a certain

amount of skill. All the same, I cannot call them an

attractive race, as they are cowardly and incurably given

to pilfering. The country was then very sparsely inhabited,

but it only needs irrigation, for which the many rivers give

great facilities.

The last part of the journey to Victoria leads through

a gorge at the foot of Providential Pass, as it is called,

from the fact that the pioneers on their way up

country discovered it by an accident. The scenery

here is enchanting, richly green, with cool streams

bubbling through the vegetation. The surrounding hills

are less grotesque in their aspect than those of other

parts of the country, and possess a graceful charm,

which, for the most part, is lacking in Africa. The

township of Victoria was represented at that time by

a group of straw huts. It was built on a flat plateau,

and did not seem over healthy; but that was in early

days. There were three public-houses, all doing a rattling

trade. Chief among them was Napier’s bar, kept by its

enterprising owner, whose name has been so often

mentioned since he acted as colonel of the Bulawayo

contingent at the beginning of the Matabele rebellion.

I was put up in a hut in the company of Lord Henry

Paulet and Major Browne; where I spent a fortnight

most enjoyably. From visits which I made to the

neighbouring mines I was greatly impressed with the

future prospects of this country. They were not of

course in full working order, but there was no mistaking

the indications of riches in the samples of quartz and

assays submitted to me.

From Victoria I made an excursion to the famous

ruins of Zimbabwe.* To see these had been one of the

objects that brought me to Africa; but as I found

Mr. Theodore Bent had been before me and made a

thorough examination of the ruins, I visited them rather

to satisfy my own curiosity than from any desire or

expectation of adding anything to the work of an

eminent archaeologist so much more capable of describ-

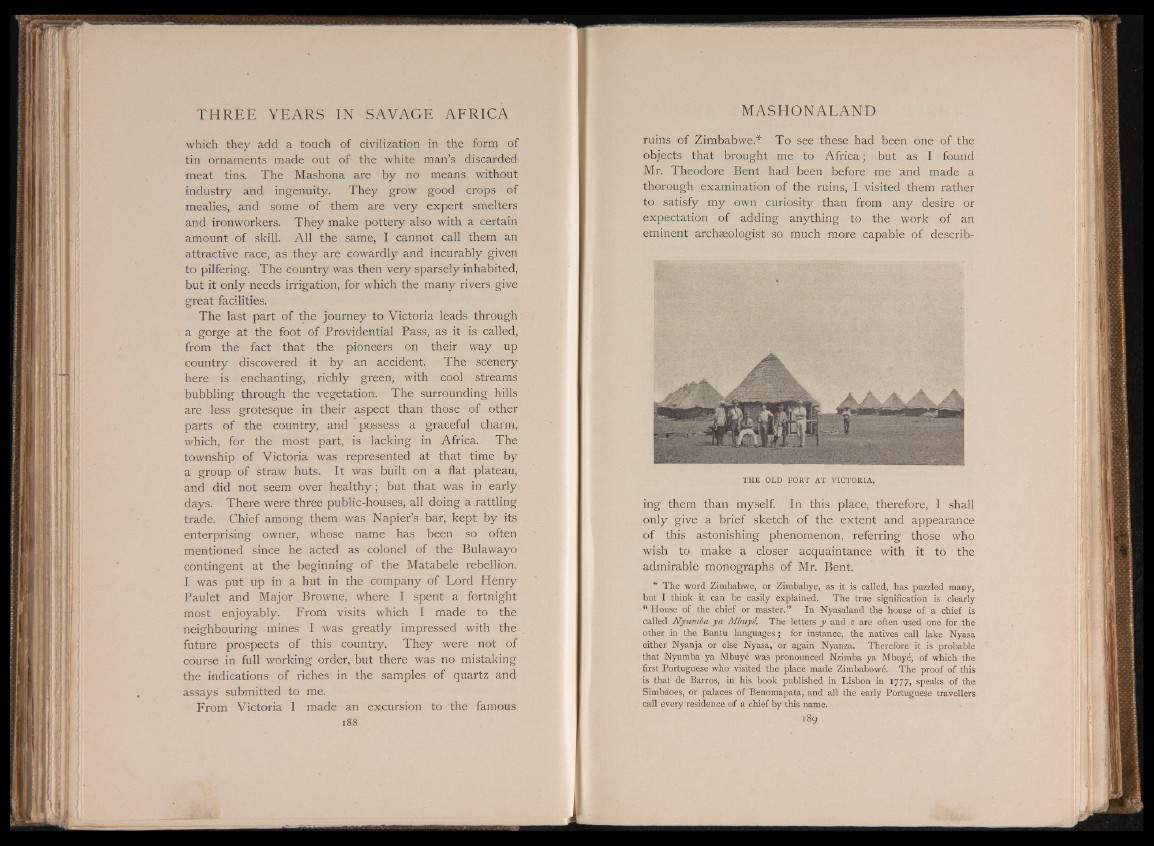

TH E OLD FORT AT VICTORIA.

ing them than myself. In this place, therefore, I shall

only give a brief sketch of the extent and appearance

of this astonishing phenomenon, referring those who

wish to make a closer acquaintance with it to the

admirable monographs of Mr. Bent.

* The word Zimbabwe, or Zimbabye, as it is called, has puzzled many,

but I think it can be easily explained. The true signification is clearly

“ House of the chief or master.” In Nyasaland the house of a chief is

called Nyumba ya MbuyL The letters y and z are often used one for the

other in the Bantu languages; for instance, the natives call lake Nyasa

either Nyanja or else Nyasa, or again Nyanza. Therefore it is probable

that Nyumba ya Mbuye was pronounced Nzimba ya Mbuye, of which the

first Portuguese who visited the place made Zimbabowe. The proof of this

is that de Barros, in his book published in Lisbon in speaks of the

Simbdoes, or palaces of Benomapata, and all the early Portuguese travellers

call every residence of a chief by this name.