euphorbus and other trees grow. The villages are dirty

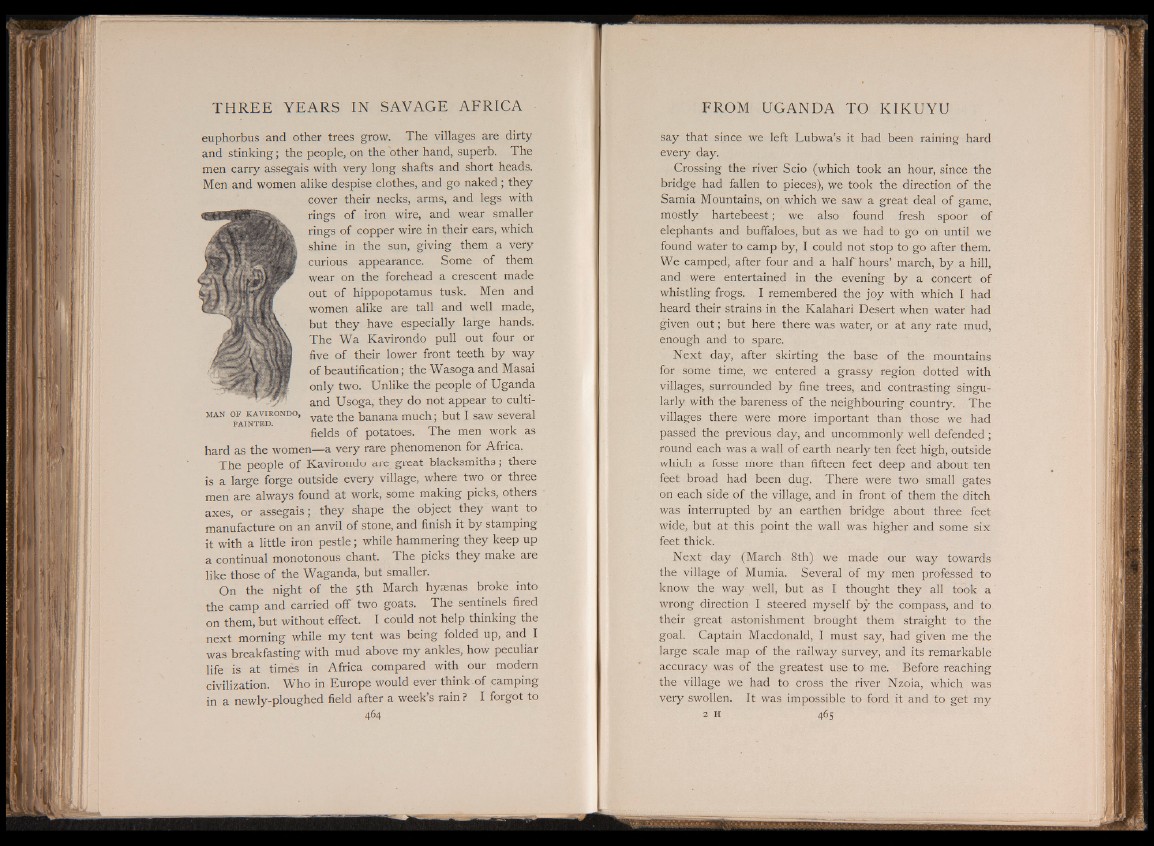

and stinking; the people, on the other hand, superb. The

men carry assegais with very long shafts and short heads.

Men and women alike despise clothes, and go naked; they

cover their necks, arms, and legs with

rings of iron wire, and wear smaller

rings of copper wire in their ears, which

shine in the sun, giving them a very

curious appearance. Some of them

wear on the forehead a crescent made

out of hippopotamus tusk. Men and

women alike are tall and well made,

but they have especially large hands.

The Wa Kavirondo pull out four or

five of their lower front teeth by way

of beautification; the Wasoga and Masai

only two. Unlike the people of Uganda

and Usoga, they do not appear to cultivate

the banana much; but I saw several

fields of potatoes. The men work as

hard as the women—a very rare phenomenon for Africa.

The people of Kavirondo are great blacksmiths; there

is a large forge outside every village, where two or three

men are always found at work, some making picks, others

axes, or assegais; they shape the object they want to

manufacture on an anvil of stone, and finish it by stamping

it with a little iron pestle; while hammering they keep up

a continual monotonous chant. The picks they make are

like those of the Waganda, but smaller.

On the night of the 5 th March hyaenas broke into

the camp and carried off two goats. The sentinels fired

on them, but without effect. I could not help thinking the

next morning while my tent was being folded up, and I

was breakfasting with mud above my ankles, how peculiar

life is at times in Africa compared with our modern

civilization. W ho in Europe would ever think -of camping

in a newly-ploughed field after a week s rain ? I forgot to

464

MAN OF KAVIRONDO,

FAINTED.

say that since we left Lubwa’s it had been raining hard

every day.

Crossing the river Scio (which took an hour, since the

bridge had fallen to pieces), we took the direction of the

Samia Mountains, on which we saw a great deal of game,

mostly hartebeest; we also found fresh spoor of

elephants and buffaloes, but as we had to go on until we

found water to camp by, I could not stop to go after them.

We camped, after four and a half hours’ march, by a hill,

and were entertained in the evening by a concert of

whistling frogs. I remembered the joy with which I had

heard their strains in the Kalahari Desert when water had

given out; but here there was water, or at any rate mud,

enough and to spare.

Next day, after skirting the base of the mountains

for some time, we entered a grassy region dotted with

villages, surrounded by fine trees, and contrasting singularly

with the bareness of the neighbouring country. The

villages there were more important than those we had

passed the previous day, and uncommonly well defended ;

round each was a wall of earth nearly ten feet high, outside

which a fosse more than fifteen feet deep and about ten

feet broad had been dug. There were two small gates

on each side of the village, and in front of them the ditch

was interrupted by an earthen bridge about three feet

wide, but at this point the wall was higher and some six

feet thick.

Next day (March 8th) we made our way towards

the village of Mumia. Several of my men professed to

know the way well, but as I thought they all took a

wrong direction I steered myself by the compass, and to.

their great astonishment brought them straight to the

goal. Captain Macdonald, I must say, had given me the

large scale map of the railway survey, and its remarkable

accuracy was of the greatest use to me. Before reaching

the village we had to cross the river Nzoia, which was

very swollen. It wras impossible to ford it and to get my

2 h 465