medicine for her stomach, as she complained of great

suffering, and thought I might be able to afford her relief.

I did my best, but I am afraid that she did not appreciate

my medicine, as she complained that “ it did not taste

bad at a ll” !

The next day, after crossing a big swamp, we arrived at

Irindi. At last we were in Unyamwezi, and I felt very

glad to think that at length I was out of Uhha. The huts

were quite different from those of the Wahha, being

pointed, with the roof descending till it almost touched

the ground, and with a little kind of verandah running

all round. By the side of each hut is a smaller one for

the Musimo, such as I have before described ; the natives

preserve their grain by storing it in immense bottles of

wood, some of them over six feet high.

I found the Wanyamwezi very differejnt from their

Wahha neighbours. I was greeted most hospitably in all

the villages I came across. I was only disturbed several

times by lions that broke out among the cattle during the

night, and at the end of five days, on July 23, I arrived at

Urambo. I had written to Mr. Shaw, the missionary in

charge of the London Missionary Society’s station,

announcing my arrival, and saying that I expected to

stop at a native village that day. I did not wish to. arrive

at the Mission on a Sunday ; but on the way some

messengers arrived with a charming letter begging me to

come straight on. The country we crossed was thickly

strewn with villages, and after a march of three hours and

a half we arrived at the Mission. Mr. Shaw received me

with the greatest kindness and cordiality; his wife was a

charming, elegant, and refined lady. She was the proud

mother of an adorable baby, who seemed to be in the best

of health, and who had not the curious waxy complexion

so common to white children brought up in Africa.

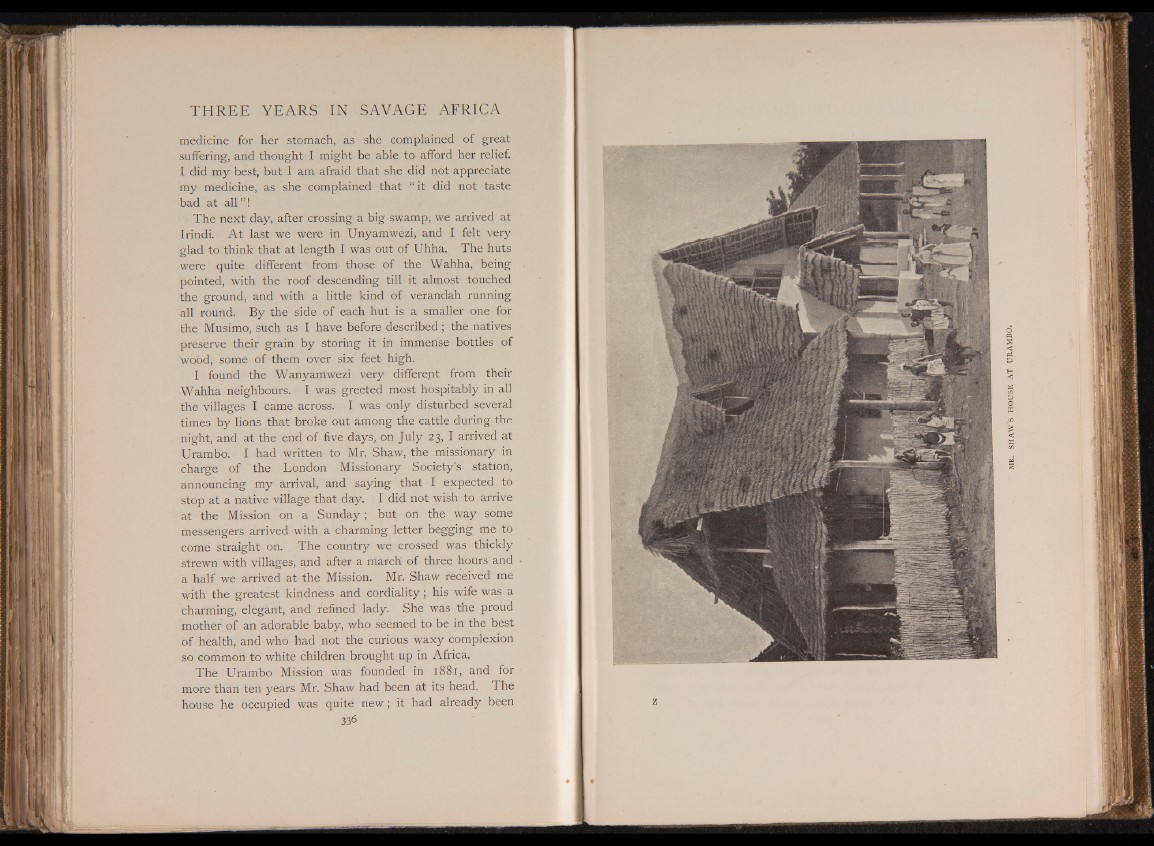

The Urambo Mission was founded in 1881, and for

more than ten years Mr. Shaw had been at its head. The

house he occupied was quite new; it had already been

336