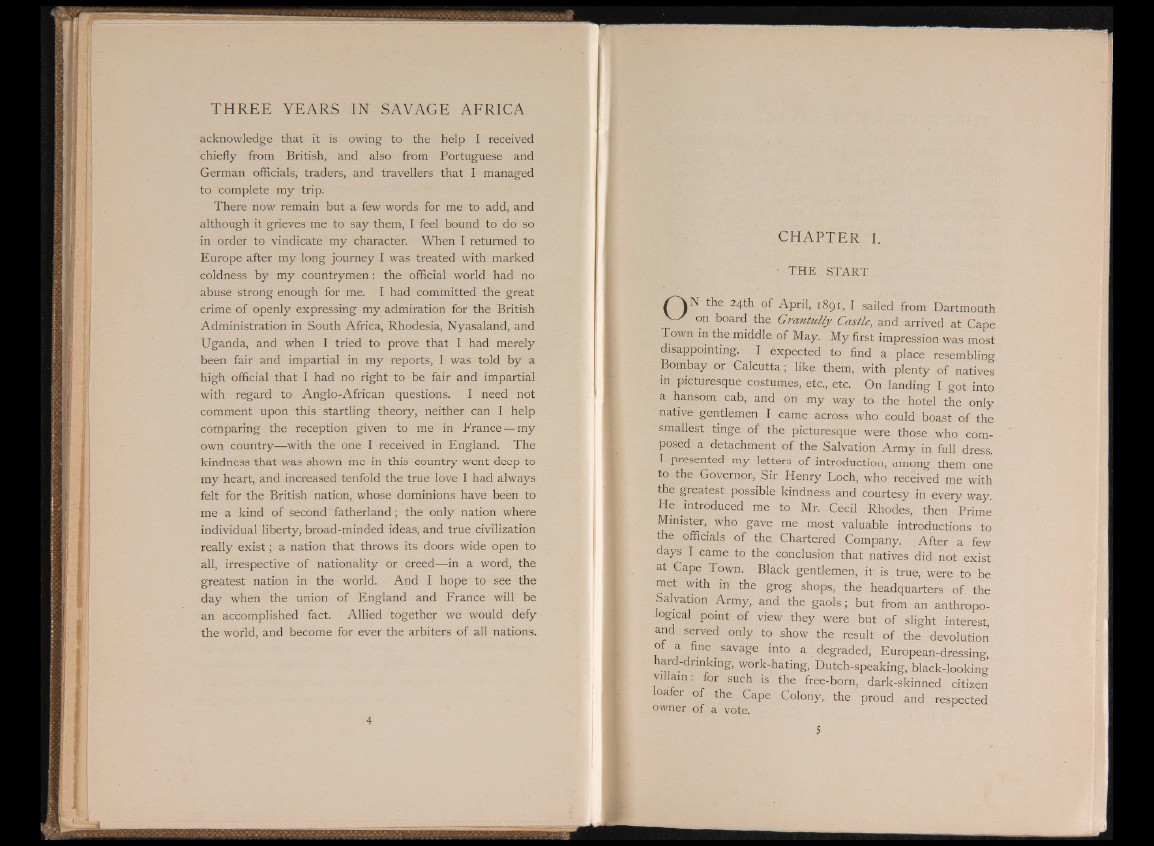

acknowledge that it is owing to the help I received

chiefly from British, and also from Portuguese and

German officials, traders, and travellers that I managed

to complete my trip.

There now remain but a few words for me to add, and

although it grieves me to say them, I feel bound to do so

in order to vindicate my character. When I returned to

Europe after my long journey I was treated with marked

coldness by my countrymen: the official world had no

abuse strong enough for me. I had committed the great

crime of openly expressing my admiration for the British

Administration in South Africa, Rhodesia, Nyasaland, and

Uganda, and when I tried to prove that I had merely

been fair and impartial in my reports, I was told by a

high official that I had no right to be fair and impartial

with regard to Anglo-African questions. I need not

comment upon this startling theory, neither can I help

comparing the reception given to me in France—my

own country—with the one I received in England. The

kindness that was shown me in this country went deep to

my heart, and increased tenfold the true love I had always

felt for the British nation, whose dominions have been to

me a kind of second fatherland; the only nation where

individual liberty, broad-minded ideas, and true civilization

really exist; a nation that throws its doors wide open to

all, irrespective of nationality or creed—in a word, the

greatest nation in the world. And I hope to see the

day when the union of England and France will be

an accomplished fact. Allied together we would defy

the world, and become for ever the arbiters of all nations.

C H A P T E R I.

• THE START

the 24th of April, 1891, I sailed from Dartmouth

on board the Grantully Castle, and arrived at Cape

Town in the middle of May. My first impression was most

disappointing. I expected to find a place resembling

Bombay or Calcutta; like them, with plenty of natives

in picturesque costumes, etc., etc. On landing I got into

a hansom cab, and on my way to the hotel the only

native gentlemen I came across who could boast of the

smallest tinge of the picturesque were, those who composed

a detachment of the Salvation Army in full dress.

I presented my letters of introduction, among them one

to the Governor, Sir Henry Loch, who received me with

the greatest possible kindness and courtesy in every way.

He introduced me to Mr. Cecil Rhodes, then Prime

Minister, who gave me most valuable introductions to

the officials of the Chartered Company. After a few

days I came to the conclusion that natives did not exist

at Cape Town. Black gentlemen, it is true, were to be

met with in the grog shops, the headquarters of the

Salvation Army, and the gaols; but from an anthropological

point of view they were but of slight interest,

and served only to show the result of the devolution

of a fine savage into a degraded, European-dressing,

hard-drinking, work-hating, Dutch-speaking, black-looking

villain: for such is the free-born, dark-skinned citizen

oa er of the Cape Colony, the proud and respected

owner of a vote.