to meet us. They said they were lying in wait for the

Masai, who had attacked them recently, and from whom

they anticipated a fresh invasion.

Next day, after climbing the hill Lanjora, we got a

fine view of the plain of Machakos, and three hours and

a halfs march brought us down to the station of Machakos.

Mr. Ainsworth, the officer in command, has made a

charming spot of this station. The whole place is

planted with masses of bananas and flowers, which give

it a thoroughly homelike appearance. Mr. Ainsworth

had been here two years, and had obtained a great

influence over the natives, who were not only well

disposed towards Europeans, but willing to give their

active support to the administration. It appeared from

what he said that it was from an attack on this station

that the Masai, whom I met at Lake Naivasha, were

returning. They had, however, been repulsed, and had

not succeeded in capturing the Company’s cattle. They

had, notwithstanding that, afterwards surprised several

Wakamba villages, and taken a good many oxen and

goats from them. The Masai, as I have already said,

are in the habit of attacking at the time of the full,

moon. They wait till night comes, make their raid, and

then travel by moonlight so as to put a considerable

distance between themselves and their enemies before

daybreak.

I stayed at Machakos several days, and, from my own

observation and the information Mr. Ainsworth gave me,

I learned a good deal about the Wakamba, the last and

in many ways the most interesting tribe which I was

able to study. Their country comprises between 70,000

and 80,000 square miles, lying north-east of Mount Kilima

Njaro* and south and west of the Athi river. The

northern part of it alone, which covers about 12,000

* I have used the expression Mount Kilima Njaro, although it is redundant.

The name of the mountain is Njaro. The word Kilim a is Kiswahili,

meaning “ the mountain.”

square miles, is estimated to have a population of at least

400,000.

The East Africa Company occupied the country in

1889, and in 1891 the Wakamba, justly exasperated by

the ill-treatment they received from one of the Company’s

agents, rose against him and attacked the station. At the

time when I visited the country, however, they were, as I

have said, exceedingly friendly to the tactful administration

of Mr. Ainsworth. They are intelligent, industrious

people, and capable of very rapid improvement. Their

customs and laws indicate a power of political and civil

organization altogether different

from those of other native

races I came across.

Unlike other tribes, they

possess no paramount chief.

There is indeed in the district

of Mala one chief called

Mwatu, who is regarded as

the real chief of that province,

but he has no special title

and no special prerogatives;

nor is he hereditary, having

gained his position by prowess

in war. In reality the Wakamba

form a kind of patriarchal

republic; they are distributed

among thousands of small

villages (muchi), each one

being the property and residence

of a single family; these

contain an average of about

fifteen huts. The head of each village is the father (um-

tumia): he usually has three or four wives, each of whom

has a hut and a grain store of her own. If he is an

old man he may have grown-up sons. The married sons

form each a village of his own; the unmarried have their

■ 485

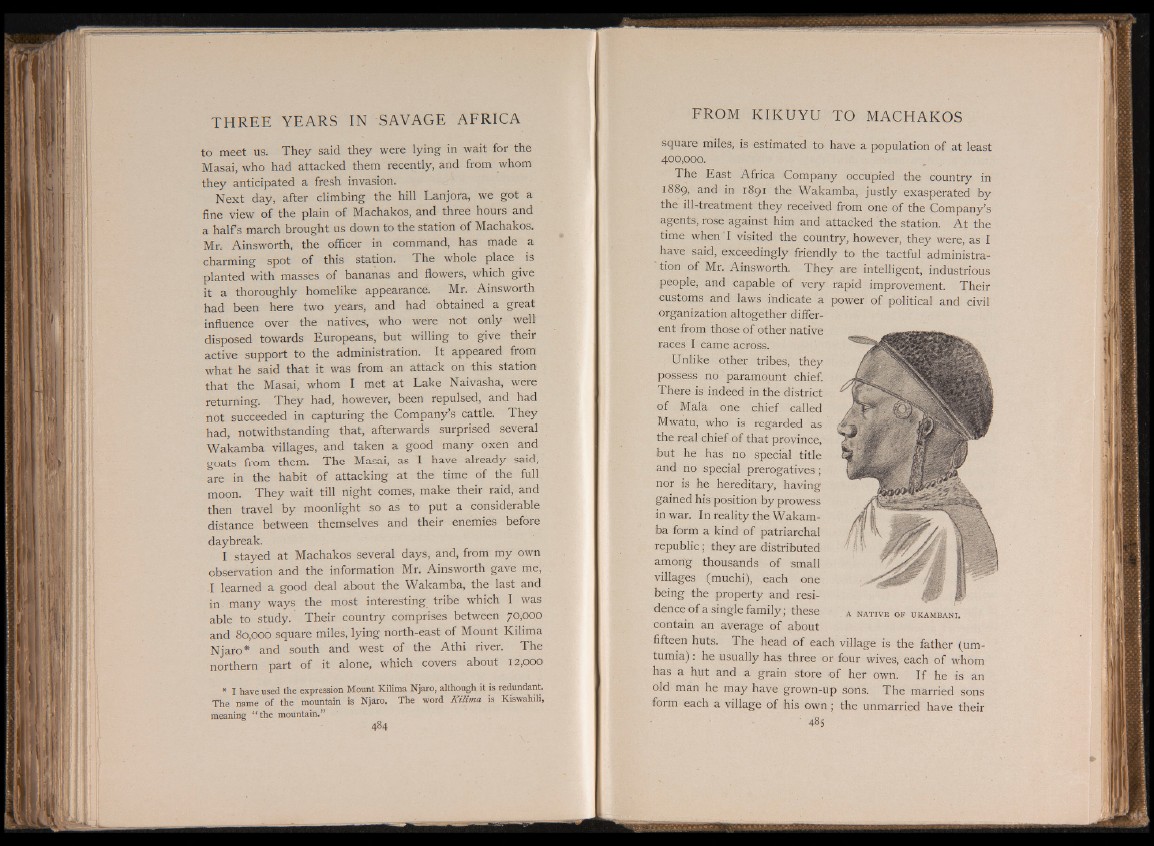

A NATIVE OF UKAMBANI.