1 50 men, their loads, and my beasts across the water, and

I could find nothing but two of the most primitive canoes I

had yet seen. They were made of a large tree-trunk,

roughly hollowed out, but on the outside left absolutely

in a state of nature. It took three hours of uninterrupted

labour to get the whole caravan to the other side. We

reached the village in the heaviest downpour I had yet

seen in Africa: for the last few days it had been raining

in torrents with hardly any interruption, and being quite

done up I was very glad to spend the next day dealing

out ten days’ rations to my men. I had to watch my

headmen measuring out more than 3000 cups of flour,

and at the end of the day I was covered all over with a

white cake of flour mixed with rain. I engaged six

men at Mumia’s to go all the way to the coast, and three

more to accompany me for the next two days. It was

only by this means that I could transport enough food

for my whole company. On leaving Mumia’s I had the

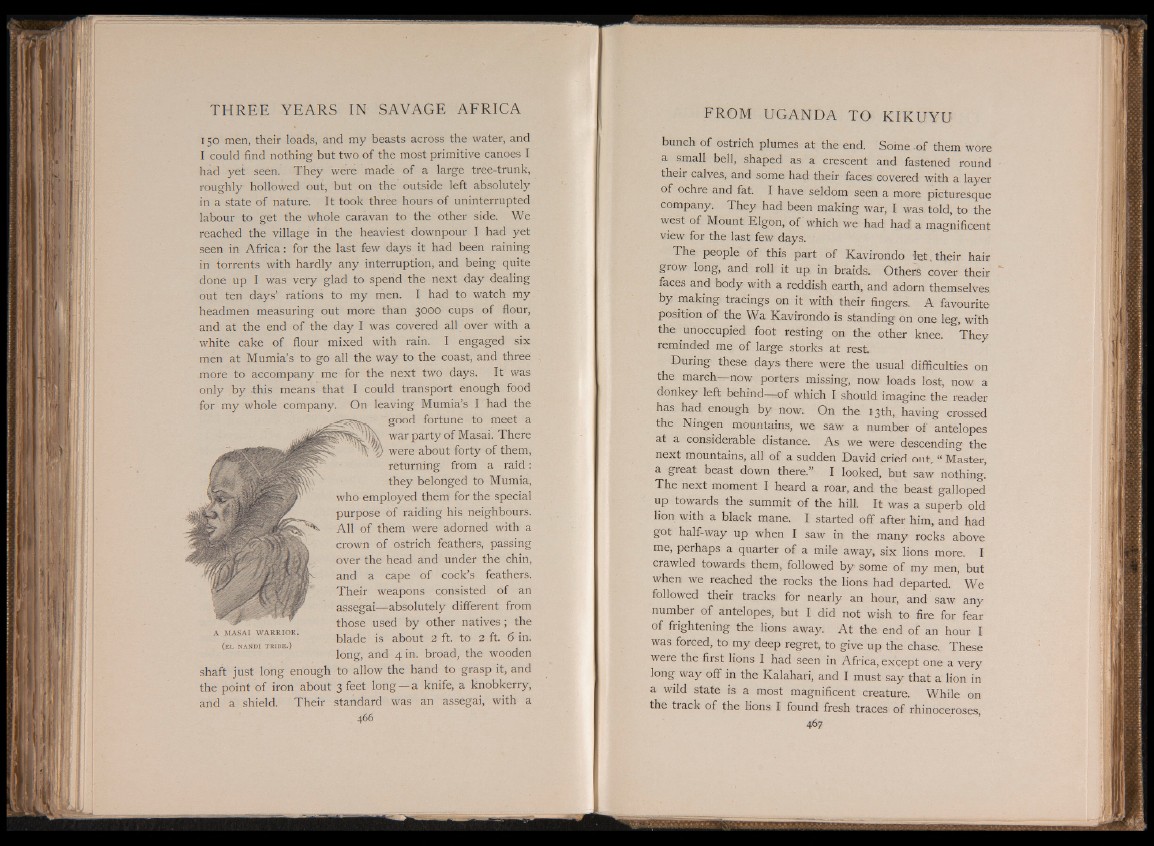

good fortune to meet a

%\ war party of Masai. There

^ V were about forty of them,

returning from a raid:

they belonged to Mumia,

who employed them for the special

purpose of raiding his neighbours.

All of them were adorned with a

crown of ostrich feathers, passing

over the head and under the chin,

and a cape of cock’s feathers.

Their weapons consisted of an

assegai—absolutely different from

those used by other natives; the

blade is about 2 ft. to 2 ft. 6 in.

long, and 4 m. broad, the wooden

shaft just long enough to allow the hand to grasp it, and

the point of iron about 3 feet long—a knife, a knobkerry,

and a shield. Their standard was an assegai, with a

466

A MASAI WARRIOR.

(e l NANDI T R IB E .)

bunch of ostrich plumes at the end. Some .of them wore

a small bell, shaped as a crescent and fastened round

their calves, and some had their faces covered with a layer

of ochre and fat. I have seldom seen a more picturesque

company. They had been making war, I was told, to the

west of Mount Elgon, of which we had had; a magnificent

view for the last few days.

The people of this part of Kavirondo fet, their hair

grow long, and roll it up in braids. Others cover their

faces and body with a reddish earth, and adorn themselves

by making tracings on it with their fingers. A favourite

position of the Wa Kavirondo is standing on one leg, with

the unoccupied foot resting on the other knee. They

reminded me of large storks at rest.

During these days there were the usual difficulties on

the march—now porters missing, now loads lost, now a

donkey left behind—of which I should imagine the reader

has had enough by now. On the 13th, having crossed

the Ningen mountains, we saw a number of antelopes

at a considerable distance. As we were descending the

next mountains, all of a sudden David cried out, “ Master,

a great beast down there.” I looked, but saw nothing.

The next moment I heard a roar, and the beast galloped

up towards the summit of the hill. It was a superb old

lion with a black mane. I started off after him, and had

got half-way up when I saw in the many rocks above

me, perhaps a quarter of a mile away, six lions more. I

crawled towards them, followed by some of my men, but

when we reached the rocks the lions had departed. ’ We

followed their tracks for nearly an hour, and saw any

number of antelopes, but I did not wish to fire for fear

of frightening the lions away. At the end of an hour I

was forced, to my deep regret, to give up the chase. These

were the first lions I had seen in Africa, except one a very

long way off in the Kalahari, and I must say that a lion in

a wild state is a most magnificent creature. While on

the track of the lions I found fresh traces of rhinoceroses,

467