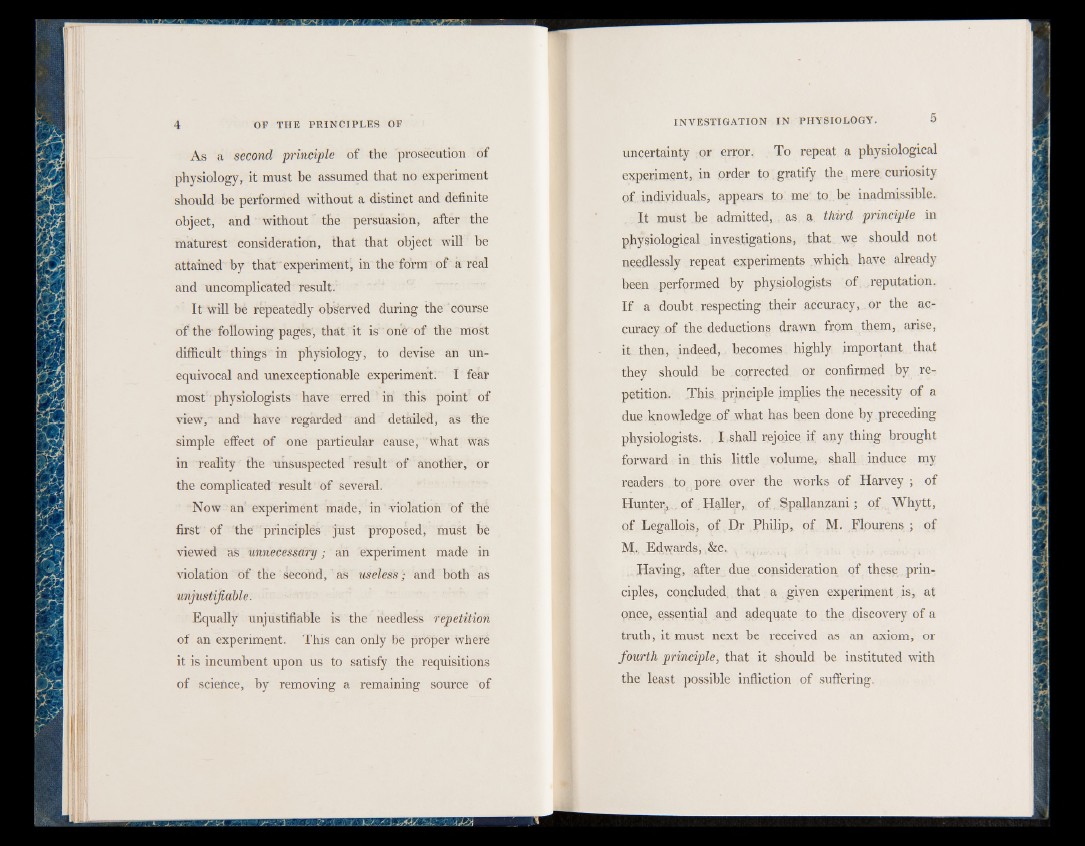

As a second principle of the prosecution of

physiology, it must be assumed that no experiment

should be performed without a distinct and definite

object, and without the persuasion, after the

maturest consideration, that that object will he

attained by that "experiment, in the form of a real

and uncomplicated result.

It will be repeatedly observed during the course

of the following pages, that it is one of the most

difficult things in physiology, to devise an unequivocal

and unexceptionable experiment. I fear

most physiologists have erred in this point of

view, and have regarded and detailed, as the

simple effect of one particular cause, what was

in reality the unsuspected result of another, or

the complicated result of several.

Now an experiment made, in violation of the

first of the principles just proposed, must be

viewed aS unnecessary | an experiment made in

violation of the Second,' as useless; and both as

unjustifiable.

Equally unjustifiable is the needless repetition

of an experiment. This can only be proper where

it is incumbent upon us to satisfy the requisitions

of science, by removing a remaining source of

uncertainty or error. To repeat a physiological

experiment, in order to gratify the mere curiosity

of individuals, appears to me to be inadmissible.

It must be admitted, as a third principle in

physiological investigations, that we should not

needlessly repeat experiments which have already

been performed by physiologists of .reputation.

If a doubt respecting their accuracy, or the accuracy

.of the deductions drawn from them, arise,

it then, indeed, becomes highly important that

they should be corrected or confirmed by repetition.

This principle implies the necessity of a

due knowledge, of what has been done by preceding

physiologists. . I .shall rejoice if any thing brought

forward in this little volume,, shall induce my

readers to pore over the works of Harvey ; of

Hunter, of Haller, of Spallanzani; of Whytt,

of Legallois, of Dr Philip, of M. Flourens ; of

M,. Edwards, &c.

Having, after due consideration of these principles,

concluded, that a giyen experiment, is, at

Once, essential and adequate to the discovery of a

truth, it must next be received as an axiom, or

fourth principle, that it should be instituted with

the least possible infliction of suffering.