Of those produced at the Gardens of the Zoological' So-*

ciety, thé young birds in the middle of last August, when

about ten weeks old, the beak was of a dull flesh colour, the

tip and lateral margins black; the head, neck, and all the

upper surface of the body pale ash brown ; the under surface

before the legs of a paler brown; the portion behind the legs

dull white ; the legs, like the beak, of a dingy flesh colour.

The same young birds, in the middle of October, have “the

beak black at the end; a reddish orange band across the

nostrils, the base and lore pale greenish-white ; the i general

colour pale greyish-brown ; a few of the smaller wing^Co verts

white, mixed with others of a pale buffy brown; the legs

black.

The young Hoopers bred in 1839, had lost almost all

their brown feathers at the autumn moult of 1840, and before

their second winter was over they were entirely'white; the

base of the beak lemon yellow.

The internal distinctions of the Hooper are more conspicuous

than those which have -been referred to as external,

and of the former, the organ of voice furnishes the ms§j|J

valuable and decisive characters. This peculiarity was known

to Willughby, but it was previously noticed by Sir Thomas

Browne, who mentions “ that strange recurvation of the windpipe

through the sternum?’

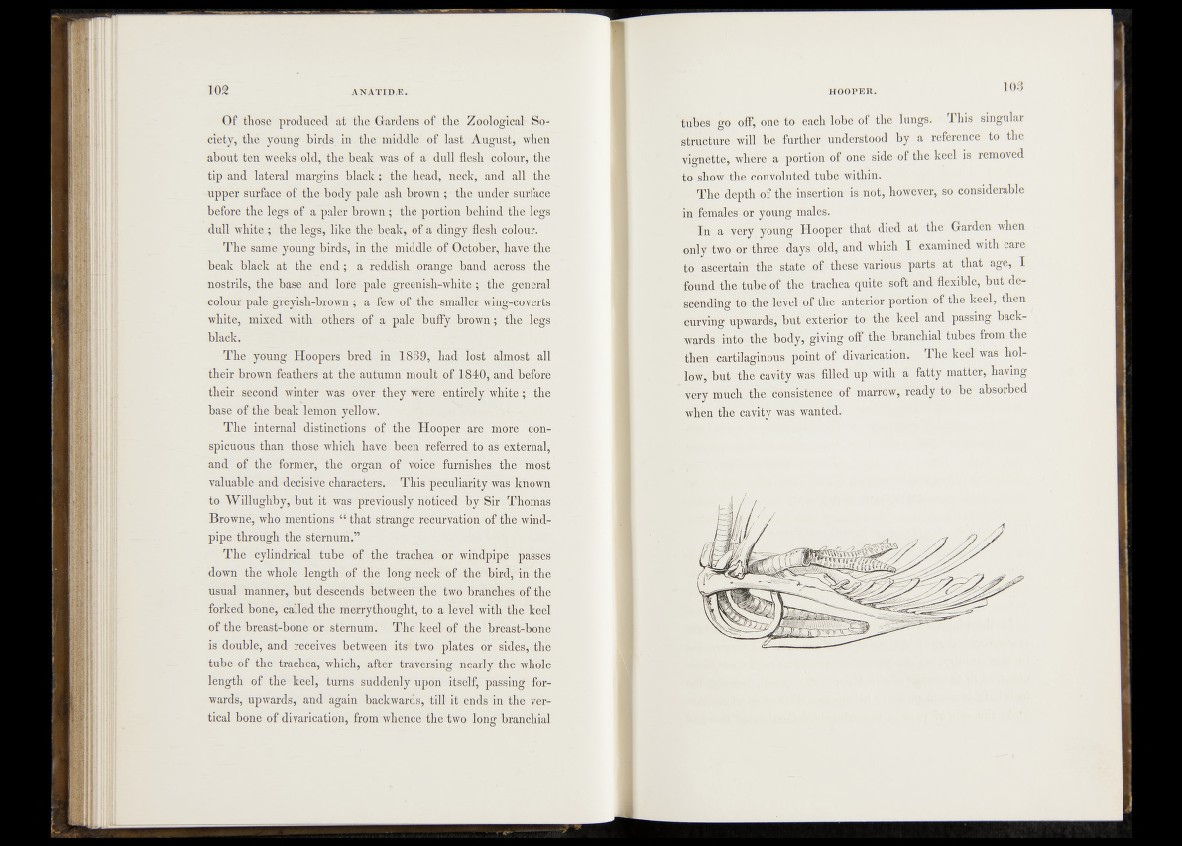

The cylindrical tube of the trachea or windpipe passes

down the whole length of the long neck of the bird, in the

usual manner, but descends between the two branches of the

forked bone, called the merrythought, to a level with the keel

of the breast-bone or sternum. The keel of the breast-bone

is double, and receives between its two plates or sides, the

tube of the trachea, which, after traversing nearly the whole

length of the keel, turns suddenly upon itsélf, passing forwards,

upwards, and again backwards, till it ends in the vertical

bone of divarication, from whence the two long branchial

tubes go off, one to each lobe of the lungs. This singular

structure will be furthek understood by a reference to the

vignette, where a portion of one side of the keel is removed

to show the convoluted tube within.

The depth of the insertion is not, however, so considerable

in females or young males.

In a very young Hooper' that died at 'the Garden when

only two or three days old, and which I examined with care

to ascertain the state of these various parts at that age, I

found the tube of the trachea quite soft and flexible, but descending

to the level of the anterior portion of the keel, then

curving upwards, but exterior to the keel and passing backwards

into _the body, giving off the branchial tubes from the

then cartilaginous point of divarication. The keel was hollow,

but the cavity was filled up with a fatty matter, having

tig ty much the consistence of marrow, ready to be absorbed

when the cavity was wanted.

/