made to' his paternal Shade with the object of regaining

health.

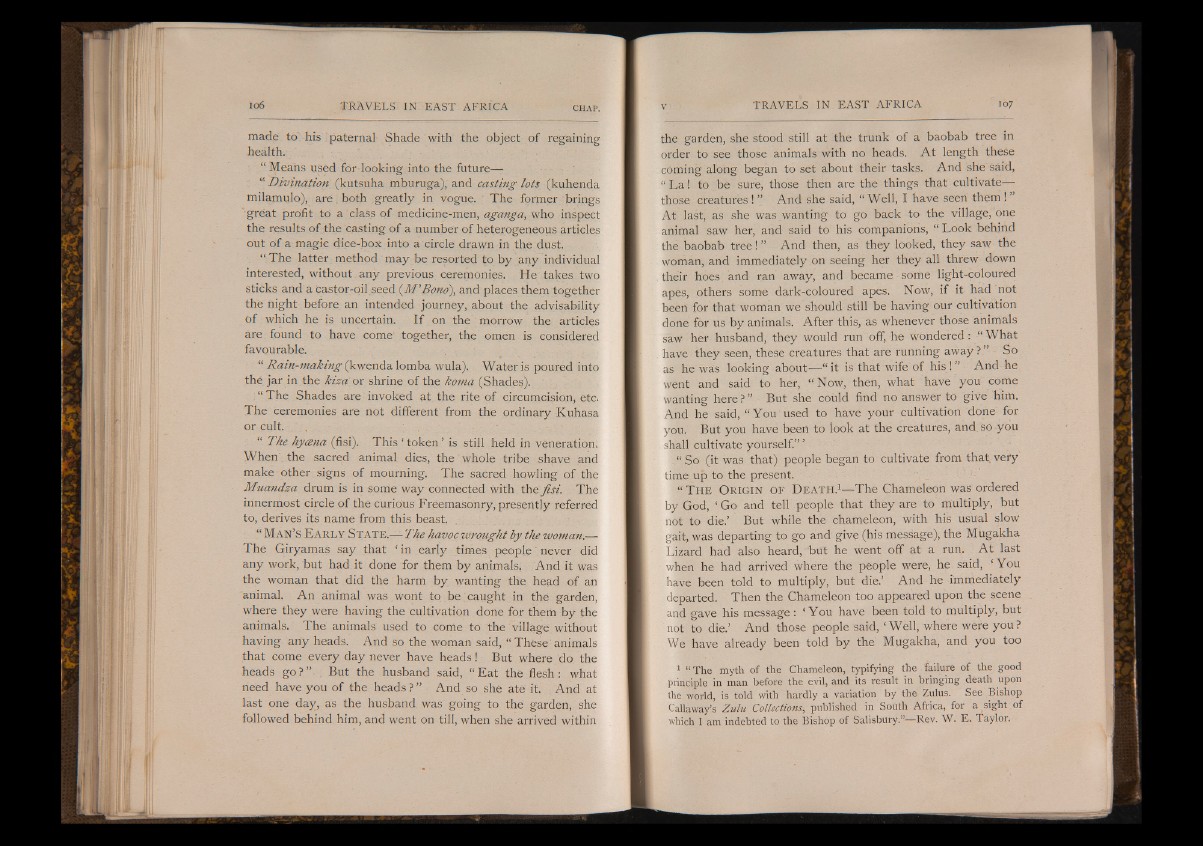

“ Means used for looking into the future—

“ Divination (kutsuha mburuga), and casting lots (kuhenda

milamulo), a re. both greatly in vogue. The former brings

"great profit to a class of medicine-men, aganga, who inspect

the results of the casting of a number of heterogeneous articles

out of a magic dice-box into a circle drawn in the dust.

“ The latter method may be resorted to by any individual

interested, without any previous ceremonies. He takes two

sticks and a castor-oil seed (M'Bono), and places them together

the night before an intended journey, about the advisability

of which he is uncertain. I f on the morrow the articles

are found to have come together, the omen is considered

favourable.

“ Rain-making (kwenda lomba wula). Water is poured into

thé jar in the kiza or shrine of the koma (Shades).

: “ The Shades are invoked at the rite of circumcision, etc.

The ceremonies are not different from the ordinary Kuhasa

or Cult.

: “ The hycena (fisi). This ‘ token ’ is still held in veneration.

When' the sacred animal dies, the whole tribe shave and

make other signs of mourning. The sacred howling of the

Muandza drum is in some way connected with the fisi. The

innermost Circle of the curious Freemasonry, presently referred

to, derives its name from this beast.

“ M a n ’s E a r l y S t a t e .— The havoc wrought by the woman.—

The Giryamas say that ‘ in early times people never did

any work, but had it done for them by animals. And it was

the woman that did the harm by wanting the head of an

animal. An animal was wont to be caught in the garden,

where they were having the cultivation done for them by the

animals. The animals used to come to the village without

having any heads. And so the woman said, “ These animals

that come every day never have heads! But where do the

heads g o ? ” . , But the husband said, “ Eat the flesh : what

need have you of the heads?” And so she ate it. And at

last one day, as the husband was going to the garden, she

followed behind him, and went on till, when she arrived within

the garden, she stood still at the trunk of a baobab tree in

order to see those animals with no heads. A t length these

coming along began to set about their tasks. And she said,

“ L a ! to be sure, those then are the things that cultivate—

those creatures ! ” And she said, “ Well, I have seen them ! ”

At last, as she was wanting to go back to the village, one

animal saw her, and said to his companions, “ Look behind

the baobab tree! ” And then, as they looked, they saw the

woman, and immediately on seeing her they all threw down

their hoes, and ran away, and became some light-coloured

apes, others some dark-coloured apes. Now, if it had not

been for that woman we should still be having our cultivation

done for us by animals. After this, as whenever those animals

saw her husband, they would run off, he wondered: “ What

have they seen, these creatures that are running away ? So

as he was looking about— “ it is that wife of h is !” And he

went and said to her, “ Now, then, what have you come

wanting here ? ” But she could find no answer to give him.

And he said, “ You used to have your cultivation done for

you. But you have been to look at the creatures, and so you

shall cultivate yourself.” ’

“ So (it was that) people began to cultivate from that, very

time up to the present.

“ T h e O r i g i n o f D e a t h .1— The Chameleon was ordered

by God, ‘ Go and tell people that they are to multiply, but

not to die.’ But while the chameleon, with his usual slow

gait, was departing to go and give (his message), the Mugakha

Lizard had also heard, but he went off at a run. A t last

when he had arrived where the people were, he said, ‘ You

have been told to multiply, but die.’ And he immediately

departed. Then the Chameleon too appeared upon the scene

and gave his message: ‘ You have been told to multiply, but

not to die.’ And those people said, ‘Well, where were you?

We have already been told by the Mugakha, and you too

1 “ The myth of the Chameleon, typifying the failure of the good

principle in man before the evil, and its result in bringing death upon

the world, is told with hardly a variation by the Zulus. See Bishop

Callaway’s Zulu Collections, published in South Africa, for a sight of

which I am indebted to the Bishop of Salisbury.”— Rev. W. E. Taylor.