coral-stone lime, evidently an article of export, together with

piles of fresh-cut mangrove borities.

A t 6.40 a.m. I reached Yabógi, another small village, situated

on rising ground on the western end of Bajimali sea-

creek, and fringed on the S.E. and south side by mangroves,

the plain beyond being covered with low prickly bushj

scattered Hyphsene, and thick clumps of fan palms. The

Hyphaenes were all tapped. Soil yellow and sandy. .

A t 7 a.m. I reached Tundwa, a large and prosperous-

looking village, with numerous good houses built of coral-

stone, and surrounded by fenced-in gardens. Coral-stone

was abundant, and I passed many heaps of freshly-burnt

coral-lime. The water supply was good, and appeared

abundant. It took me ten minutes to walk through the

village, around which luxuriant groves of coco-nuts were

growing in a white to yellow sandy soil.

From Tundwa onwards, excepting one or two mangrove

swamps on my left, cultivation continued steadily, the lay of

the country being very flat; coco-nuts were very numerous,

and as a rule very thickly planted, often lanky and tapering;

the undergrowth is apparently only cut down periodically,

and this, with excessive tapping for toddy, would doubtless

account for their unhealthy appearance ; the Hyphaene palms

appeared almost as numerous as the coco-nuts. On the

uncultivated portions the ground was covered with thick fan-

palm clumps, low mimosas and thorny scrub— the soil everywhere

being very sandy, in colour white to grey and latterly

yellow. Mango trees with an occasional tamarind were also

frequent, and I was particularly struck, not only with the

number, but the extraordinarily large size of the cashew-nut

trees (.Anacardium occidentale), the finest I had ever seen;

many of them were as large and luxuriant as mangoes.

In a coco-nut shamba that I passed I noticed that young

plants had been planted to fill up gaps amongst the older

trees, which were nearly all lanky and some dying. It is a

question whether the death of these trees has been caused by

neglect or by excessive tapping for toddy. All the fields

were then being cleared in readiness for sowing.

A t 9 a.m. I halted to allow one of my Bajoni askaris to go

on ahead to deliver the letters I was bringing to the Wa-Siyu

head-men, and to advise them of my Goming. Siyu being

now visible in the distance, with a thick fringe of coco-nut

trees behind it, I halted under a borassus palm, and whilst

resting, several women passed me carrying cut strips of fan-

palm leaves, tied into bundles, for making mats and rope.

After ten minutes’ halt I started again for Siyu, which I

reached at 9.25 a.m., it having taken me exactly two and a

half hours— deducting thirty-five minutes for various halts—•

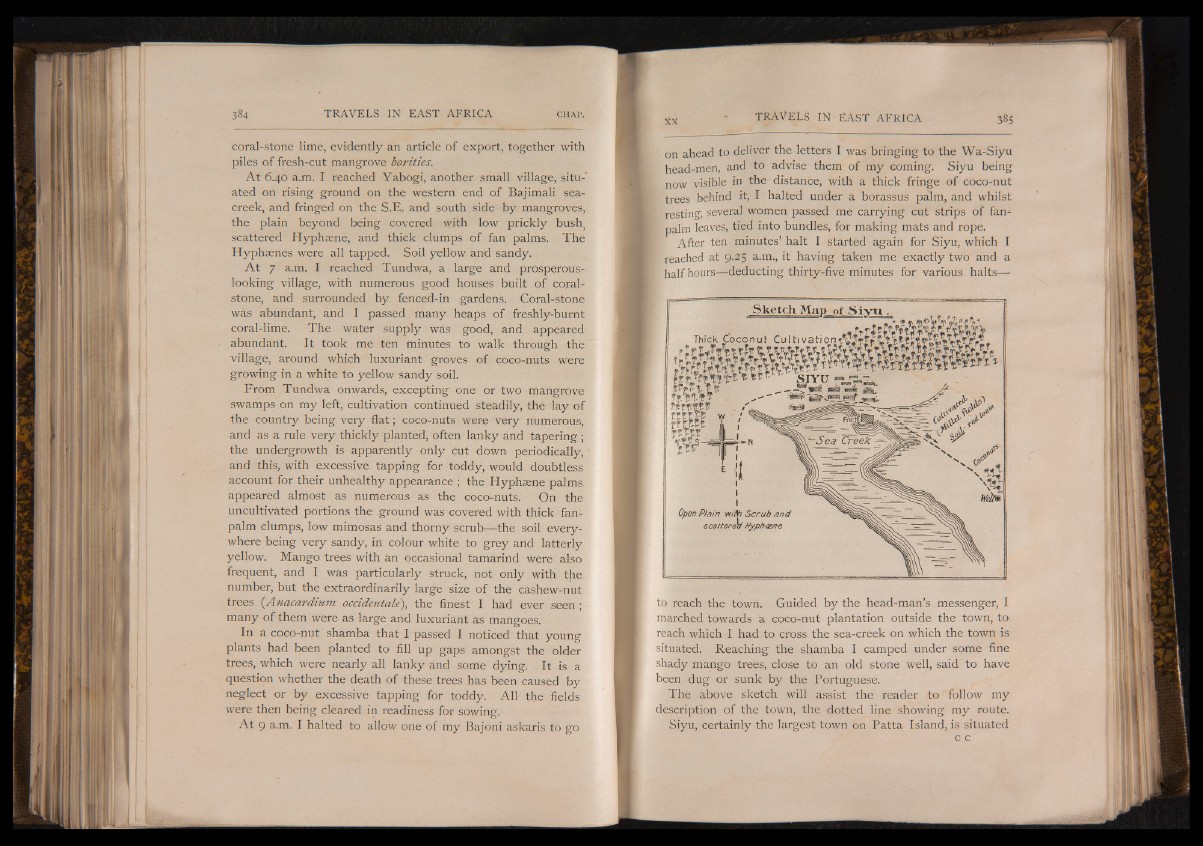

S k e tch Map of S i y u .

Thick Coconut Cultivati

r! p iJ r v w h t

f

I

tr-ni&K

t .n ip I - ;

r ttlU i

Open Plain with Scrub „

scattered Hyphaene

to reach the town. Guided by the head-man’s messenger, I

marched towards a coco-nut plantation outside the town, to

reach which I had to cross the sea-creek on which the town is

situated. Reaching the shamba I camped under some fine

shady mango trees, close to an old stone well, said to have

been dug or sunk by the Portuguese.

The above sketch will assist the reader to follow my

description of the town, the dotted line showing my route.

Siyu, certainly the largest town on Patta Island, is situated