repeated mention of a real forest, and a large one, but the

information was very vague, and, I suspected, purposely so.

Mohamed bin Saif told me that the Gallas lived in a big

forest, and I was informed that all the elephants came from

the Galla country. A boy who had been there said there was

a big forest, with trees large enough to make canoes. These

Wa-Galla were said to trade only in honey and ivory.

In illustration of the fear inspired in the Watiku by the

Gallas, I was told of a man from Tula having shot an elephant

and taken the tusks to his village, whereupon the Gallas

demanded them under threat of seizing some of the Tula

children and making them slaves, as well as declaring war.

The tusks were given up, accompanied by a propitiatory gift

of money. I also heard that only a few days back some

Gallas walked into Burkau, and killed and ate a sheep without

paying for it. These facts now made me understand the

reluctance of 'the head-man to help me to penetrate into the

Galla country.

The cultivation round Burkau was chiefly metamah, a little

sim-sim, and some tobacco. Cotton was not grown, but it

would grow well, and the Watiku stated that the whole

country from Mattaroni upwards was excellently adapted for

its cultivation. The Watiku extend along the coast almost up

to Kismayu, in scattered villages considerable distances apart,

owing to their jealousy and distrust of one another, particularly

on the part of the head-men. The names of the Watiku villages

north of Burkau were—

1. Tosha, six hours from Burkau.

2. Gudaki, one and a half hours from Tosha.

3. M’Dava (an island), one hour’s sail with S.W. wind.

4. Tula, also an island.

5. Shwe, another island.

6. Kwaijama, two hours south of Kismayu.

Mze Saifs authority was really only acknowledged as far

as Shakan, beyond which the Waze of each village mahaged

their affairs pretty well as they liked. Everything tends to

show the gradual decay of the Watiku from their former

position; they appear never to have recovered from their

overthrow by the Gallas.

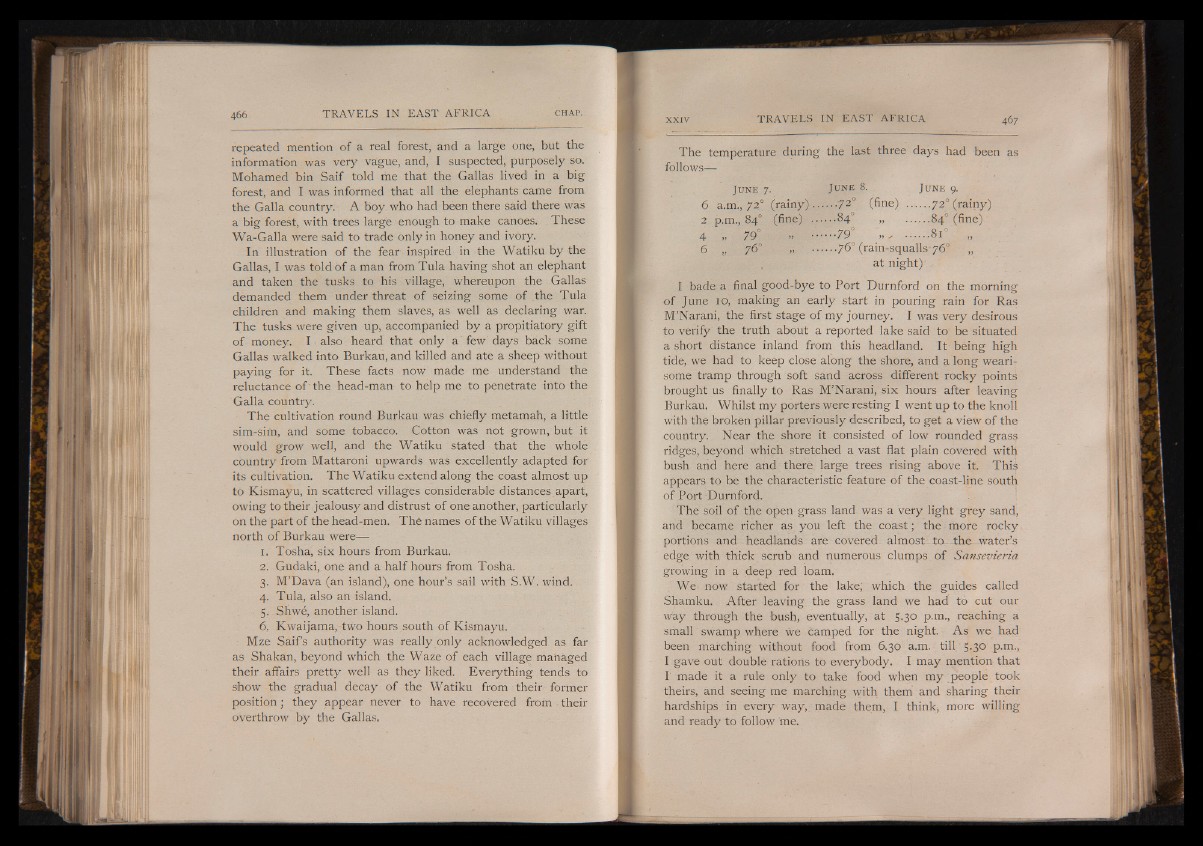

The temperature during the last three days had been as

follows—

Ju n e 8. Ju n e 9.

...72° (fine) ....... 720 (rainy)

• •84° 84° (fine)'

I 7 9 ° ......8i° „

.. 76° (rain-squalls* 76° „

at night)'

Ju n e 7.

6 a.m., 72° (rainy)

2 p.m., 84° (fine)

4 „ 79°

6 „ 76° Ì

I bade a final good-bye to Port Durnford on the morning

of June 10, making an early start in pouring rain for Ras

M’Narani, the first stage of my journey. I was very desirous

to verify the truth about a reported lake said to be situated

a short distance inland from this headland. It being high

tide, we had to keep close along the shore, and a long wearisome

tramp through soft sand across different rocky points

brought us finally to Ras M’Narani, six hours after leaving

Burkau. Whilst my porters were resting I went up to the knoll

with the broken pillar previously described, to get a view of the

country. Near the shore it consisted of low rounded grass

ridges, beyond which stretched a vast flat plain covered with

bush and here and there large trees rising above it. This

appears to be the characteristic feature of the coast-line south

of Port Durnford.

The soil of the open grass land was a very light grey sand,

and became richer as you left the coast ; the more rocky

portions and headlands are covered- almost- to- the water’s

edge with thick scrub and numerous clumps of Sansevieria

growing in a deep red loam.

We now started for the lake; which the guides called

Shamku. After leaving the grass land we had to cut our

way through the bush, eventually, at 5.30 p.m., reaching a

small swamp where we camped for the night. As we had

been marching without food from 6.30 a.m. till 5.30 p.m.,

I gave out doublé rations to everybody. I may mention that

I made it a rule only to take food when my people took

theirs, ànd seeing me marching with them and sharing their

hardships in every way,, made them, I think, more willing

and ready to follow me.