on this island, to which I proceeded direct from Lamu by

dhow, my first destination being the town of Paza or Faza.

The journey lasted from 7 a.m. to 6.30 p.m. My arrival was

so strange an event that the whole town turned out to witness

it. Mze Saif, the chief of the place, to whom I brought letters,

was, I found, absent on the mainland, but his sons welcomed

me, and offered me a house; however, I preferred my tent,

and they escorted me to a coco-nut shamba outside the town

where a large, curious crowd surrounded me, and remained,

watching my every movement till quite late in the evening.

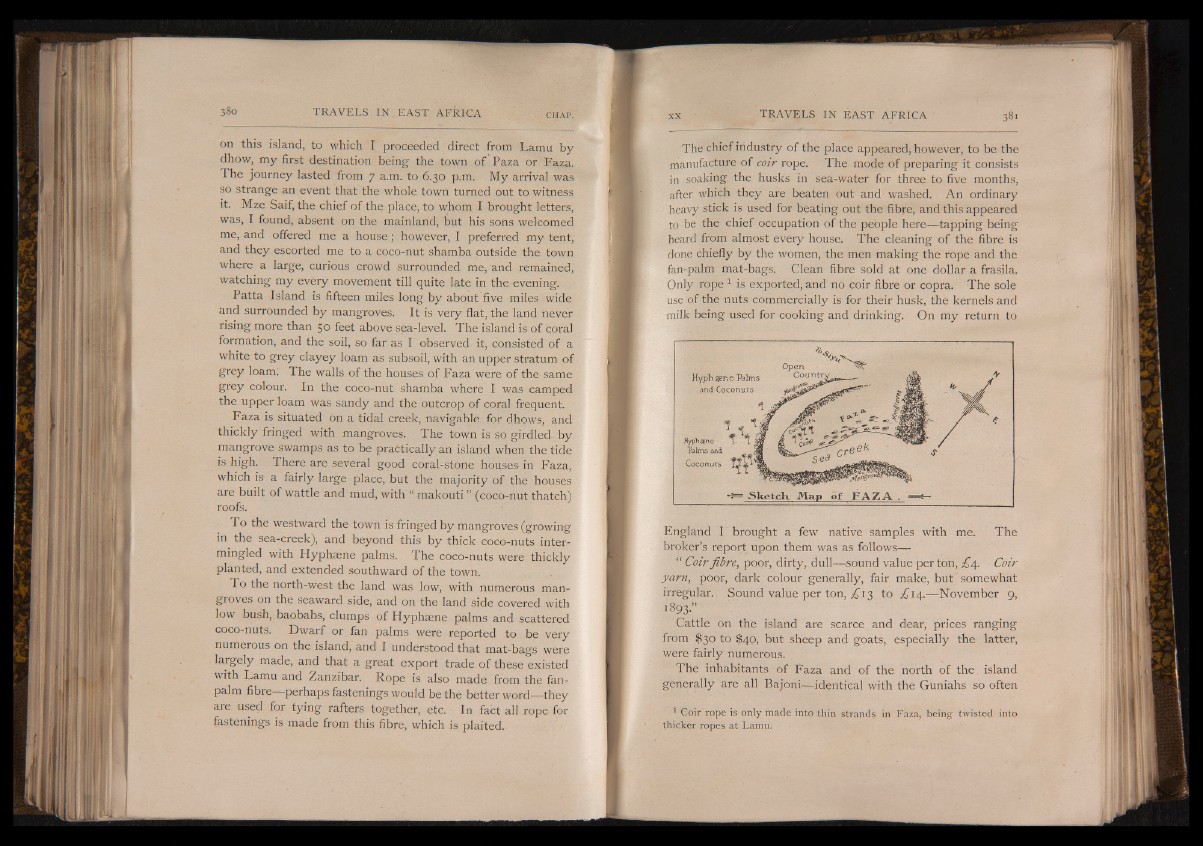

Patta Island is fifteen miles long by about five miles wide

and surrounded by mangroves. It is very flat, the land never

rising more than 50 feet above sea-level. The island is of qoral

formation, and the soil, so far as I observed it, consisted of a

white to grey clayey loam as subsoil, with an upper stratum of

grey loam: The walls of the houses of Faza were of the same

grey colour. In the coco-nut shamba where I was camped

the upper loam was sandy and the outcrop of coral frequent.

Faza is situated on a tidal creek, navigable for dhows, and

thickly fringed with mangroves. The town is so girdled by

mangrove swamps as to be practically an island when the tide

is high. There are several good coral-stone houses-in Faza,

which is a fairly large place, but the majority of the houses

are built of wattle and mud, with “ rnakouti ” (coco-nut thatch)

roofs.

To the westward the town is fringed by mangroves (growing

in the sea-creek), and beyond this by thick coco-nuts intermingled

with Hyphaene palms. The coco-nuts were thickly

planted, and extended southward of the town.

To the north-west the land was low, with numerous mangroves

on the seaward side, and on the land side covered with

low bush, baobabs, clumps of Hyphaene palms and scattered

coco-nuts. Dwarf or fan palms were reported to be very

numerous on the island, and I understood that mat-bags were

largely made, and that a great export trade of these existed

with Lamu and Zanzibar. Rope is also made from the fan-

Palm fibre— perhaps fastenings would be the better word— they

are used for tying rafters together, etc. In fact all rope for

fastenings is made from this fibre, which is plaited.

The chief industry of the place appeared, however, to be the

manufacture of coir rope. The mode of preparing it consists

in soaking the husks in sea-water for three to five months,

after which they are beaten out and washed. An ordinary

heavy stick is used for beating out the fibre, and this appeared

to be the chief occupation of the people here— tapping being

heard from almost every house. The cleaning of the fibre is

done chiefly by the women, the men making the rope and the

fan-palm mat-bags. Clean fibre sold at one dollar a frasila.

Only rope1 is exported, and no coir fibre or copra. The sole

use of the nuts commercially is for their husk, the kernels and

milk being used for cooking and drinking. On my return to

England I brought a few native samples with me. The

broker’s report upon them was as follows—

“ Coir fibre, poor, dirty, dull— sound value per ton, £4. Coir

yarn, poor, dark colour generally, fair make, but somewhat

irregular. Sound value per ton, 3 to £14.— November 9,

1893.”

Cattle on the island are scarce and dear, prices ranging

from $30 to $40, but sheep and goats, especially the latter,

were fairly numerous.

The inhabitants of Faza and of the north of the island

generally are all Bajoni— identical with the Guniahs so often

1 Coir rope is only made into thin strands in Faza, being twisted into

thicker ropes at Lamu.