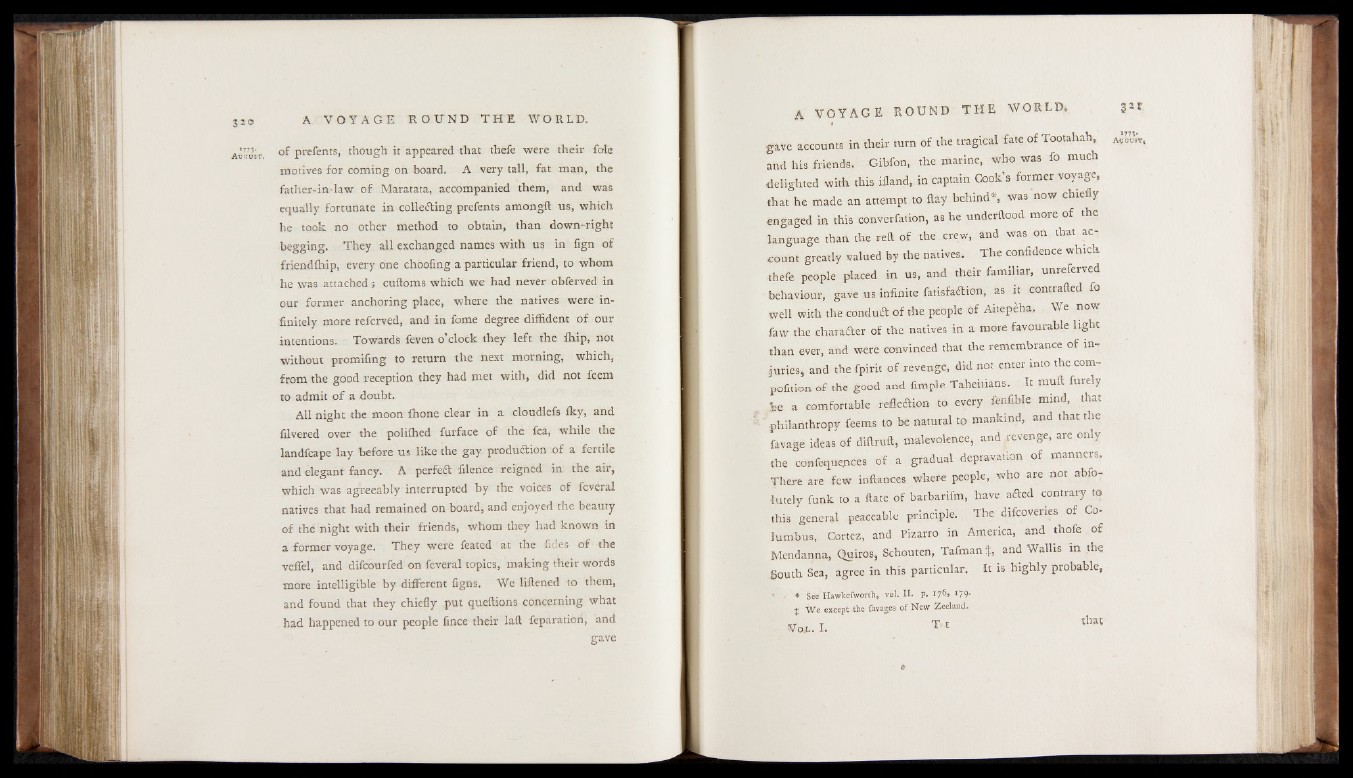

adjust of prefents, though it appeared that thefe were their foie

motives for coming on board. A very tall, fat man, the

father-in-law of Maratata, accompanied them, and was

equally fortunate in collecting prefents amongft us, which

he took no other method to obtain, than down-right

begging. They all exchanged names with us in fign of

friendfhip, every one choofing a particular friend, to whom

he was attached ; cuftoms which we had never obferved in

our former anchoring place, where the natives were infinitely

more referved, and in fome degree diffident of our

intentions. Towards feven o’clock they left the ffiip, not

without promifing to return the next morning, which,

from the good reception they had met with, did not feem

to admit of a doubt.

All night the moon fhone clear in a cloudlefs Iky, and

filvered over the poliffied furface of the fea, while the

landfcape lay before us like the gay produftion of a fertile

and elegant fancy. A perfeCt filence reigned in the air,

which was agreeably interrupted by the voices of feveral

natives that had remained on board, and enjoyed the beauty

of thé night with their friends, whom they had known in

a former voyage. They were feated at the fideS' of the

veffel, and difcourfed on feveral topics, making their words

more intelligible by different figns. We liftened to them,

and found that they chiefly put queftions concerning what

had happened to our people fince their laft feparation, and

gave

gave accounts in their turn of the tragical fate of Tootahah,

and his friends. Gibfon, the marine, who was fo much

delighted with this ifland, in captain Cook’s former voyage,

that he made an attempt to flay behind*, was now chiefly

engaged in this converfation, as he underftood more of the

language than the reft of the crew, and was on that account

greatly valued by the natives. The confidence which

thefe people placed in us, and their familiar, unreferved

behaviour, gave us infinite fatisfatftion, as it contrafted fq

well with the conduit of the people of Aitepeha. We now

faw the character of the natives in a more favourable light

than ever, and were convinced that the remembrance of injuries,

and the fpirit of revenge, did not enter into the com-

pofition of the good and fimple Taheitians. It muft furely

he a comfortable reflection to every fenfible mind, that

: philanthropy feems to be natural to mankind, and that the

favage ideas of diftruft, malevolence, and revenge, are only

the confeque.nces of a gradual depravation of manners.

There are few inftances where people, who are not abfo-

iutely funk to a ftate of barbarifm, have afled contrary to

this general peaceable principle. The difcovenes of Columbus,

Cortez, and Pizarro in America, and thofe of

Mendanna, Quiros, Schouten, Tafman %, and Wallis in the

South Sea, agree in this particular. It is highly probable,

* See Hawkefworthj vol. II. p. *7^ ’ *79*

X We except the favages of New Zeeland.

VOvL. I . T t

A^1G7U75S*Tt

that