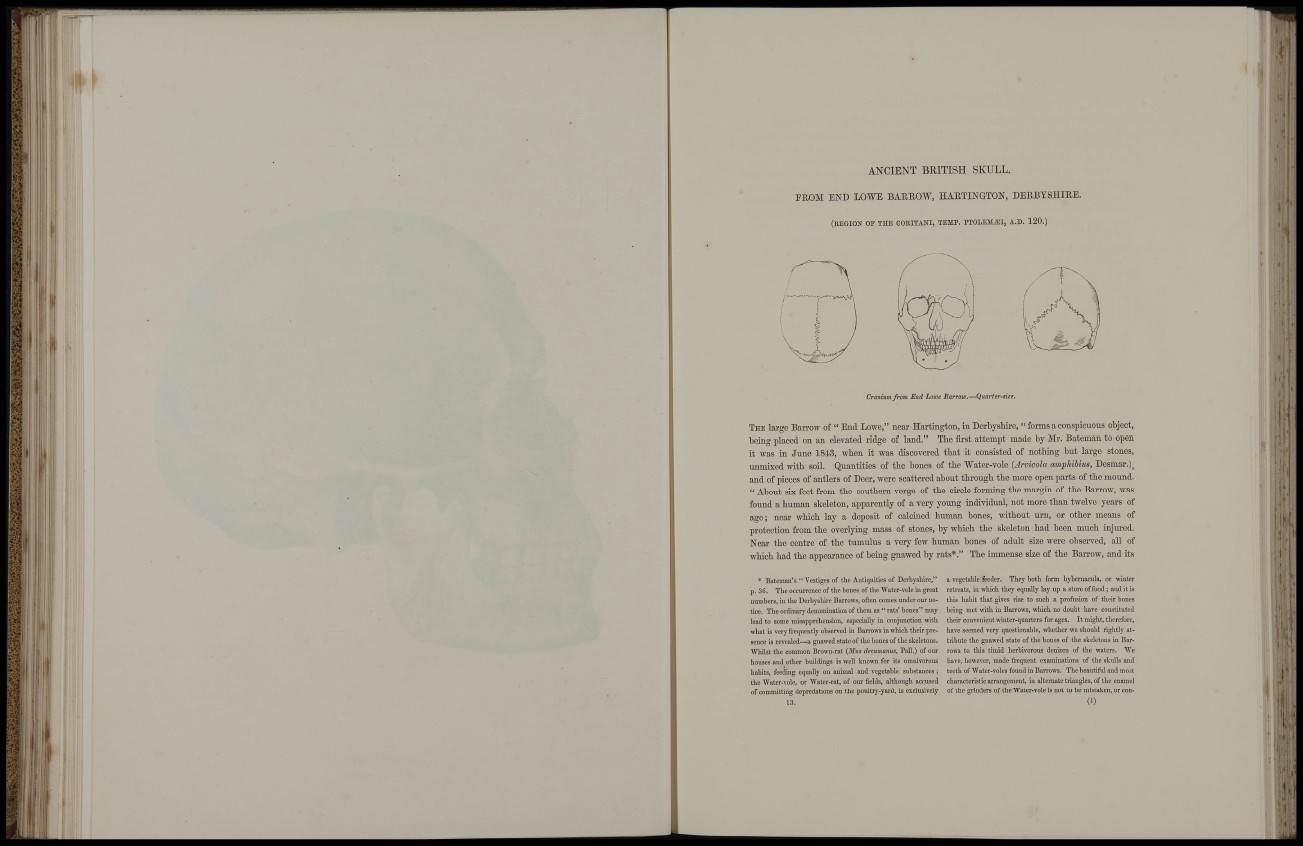

A N C I E N T BRITISH SKULL.

P R O M END LOWE BAREOW, HARTINGTON, DERBTSHIEE.

(UEGION OF TEE COEITANI, TEMP. PTOIIBMIEI, A.D. 120.)

iiitiiii ii

f ill' M

iiil

Cranium from End Lowe Barrow.—Quarter-size.

THE large Barrow of " End Lowe," near Hartington, in Derbyshire, " forms a conspicnous object,

being placed on an elevated ridge of land." The first attempt made by Mr. Bateman to open

it was ia June 1843, when it was discovered that it consisted of nothing but large stones,

unmixed with soil. Quantities of the bones of the Water-vole {Armcola amphibius, Desmar.),

and of pieces of antlers of Deer, were scattered about through the more open parts of the mound.

" About six feet from the southern verge of the cu-cle forming the margin of the Barrow, was

found a human skeleton, apparently of a very young individual, not more than twelve years of

age; near which lay a deposit of calcined human bones, without urn, or other means of

protection from the overlying mass of stones, by which the skeleton had been much injured.

Near the centre of the tumulus a very few human bones of adult size were observed, all of

which had the appearance of being gnawed by rats*." The immense size of the Barrow, and its

* Bateman's " Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire,"

p. 36. The occurrence of the hones of the Water-vole in great

numbers, in the Derbyshire Barrows, often comes uuder our notice.

The ordinary denomination of them as " rats' bones" may

lead to some misapprehension, especially in conjunction with

what is very frequently observed in Barrows in which their presence

is revealed—a gnawed state of the bones of the skeletons.

Whilst the common Brown-rat {Mits decumamis. Pall.) of our

houses and other buildings is well known for its omnivorous

habits, feeding equally on animal and vegetable substances;

the Water-vole, or Water-rat, of our fields, although accused

of committing depredations on the poultry-yard, is exclusively

13.

a vegetable feeder. They both form hybernacula, or winter

retreats, in which they equally lay up a store of food ; and it is

this habit that gives rise to such a profusion of their bones

being met with in Barrows, which no doubt have constituted

their convenient winter-quarters for ages. It might, therefore,

have seemed very questionable, whether we should rightly attribute

the gnawed state of the bones of the skeletons in Barrows

to this timid herbivorous denizen of the waters. We

have, however, made frequent examinations of the skulls and

teeth of Water-voles found in Barrows. The beautiful and most

characteristic arrangement, in alternate triangles, of the enamel

of the grinders of the Water-vole is not to be mistaken, or conf