la?

. I !

lit

ijtI'i;

DBSCEIPTIONS OF CRANIA.

the year 1815*. In six of these, the primary interment consisted of burned hones deposited in

shallow cists in the chalk, in two instances with small earthen cups, and ia one only, with a

smaU. lance-head of bronze and a bit of ivory, supposed to have beloaged to the sheath or handle

of this weapon, traces of the wood of which were found. Three of the barrows, of an elegant

bell-form, are cui'iously united within a common trench, having a sort of hour-glass shape.

Twin baiTows thus united are not uncommon, but such a threefold union is very raret- Two

of these ai-e large barrows, with an elevation of upwards of ten feet, whilst the third intermediate

mound is not more than three feet in height. In each of the large barrows, Su- R. C. Hoare

found an interment after cremation, and ia one of them the lance-head and piece of ivory above

referred to. In tliis last there was likewise a secondary interment of burned bones, hi a large

rude urn, about two feet from the summit. The small central mound was perhaps at the time

not regarded as a barrow; at least it was not examined. In August 1854, it was explored by

the writer, who found a deposit of bm-ned bones in a shallow cist, and with them a rude bone

pin nearly five inches in length, which had likewise passed through the fire. The bones were of

small size, probably those of a female. The three barrows doubtless formed a family sepulchre,

that perhaps of two brothers—with the wife of one, or perhaps of both of them, in the centre i.

The seventh barrow, which, " adjoining the sacred circle," Sir Richard says " seems to have

been the post of honour, reserved to the chief of the clan that inhabited these downs," was the

only one ia which cremation had not been practised. Dr. Stukeley teUs us, that in another

barrow immediately adjacent to the circle, which was levelled in 1720, an nnburnt skeleton was

also found, "within a bed of great stones forming a kind of arch," and with it " several beads of

amber, long and round, as big as one's thumb end, and several enamelled beads of glass, some

white and some green§." To retiu-n, however, to Sir R. 0. Hoare's description: this barrow is

about seventy-five feet in diameter and ten in elevation, the sides steeper than usual, and without

any trace of a surrounding trench; it seems to have been a simple conical or bowl barrow,

rather than of the elegant bell-form. Part of it only is seen, to the right, in the foreground of

the view on a preceding page. At the depth of ten feet, in a cist hoUowed in the chalk, was a

large male skeleton having the head to the east, and the feet to the west, being the reverse of

the position usually observed in Chi-istian cemeteries ||. The legs were gathered up under the

thighs, and the right-hand elevated towards the head. The body appeared to have been deposited

in the hollow trunk of a tree or on a plank of wood, probably ehnl", the decayed remains of

» Ancient "Wilts, vol. ii. p. 89. Stukeley, " Abuiy," p. 44.

pi. 29, gives a view of these barrows.

t The only instance to which we can refer is a still larger

triplet, near Wansdyke, at Shepherd's Shore, about five miles

to the south-west. In two of these hkewise, the interments

were after cremation : the sepulchral deposit in the other

mound has hitherto eluded discovery. Hoare, "Ancient "Wilts,"

vol. ii. p. 92. Falkner, " Archieologia," vol. xxxii. p. 457.

J Ciesar, B. G. lib. v. c. 14. " Usores hahent inter se

communes, et masime fratres cum fratribus."

§ Stukeley, "Abury," p. 44. The remains of this barrow may

possibly be the low mound in " Mill-field," which is shown

on the left in the foreground of our view. In digging into

this, in 1854, deep trenches in the chalk were uncovered, and

bits of potteiy, apparently medieeval, with several large iron

nails, were found. The mound, if not the remains of the

barrow described by Stukeley, may have been the site of a

windmill, removed perhaps prior to Aubrey's time.

II This, though not the usual position in ancient British

11.

interments, hag in a few other instances been remarked. The

object of this deviation may have been connected with the

proximity of the adjacent sacred circle, towards which the

feet and consequently the face were turned. The position reminds

us of a passage in Shakspeare, who, though no authority

in antiquarian questions, has often preserved old traditions

and curious points of learning. In the drama of

Cymbeline (Act IV. Se. 2), the scene of which is laid in

Britain in the time of Augustus, Guiderius is made to say of

the supposed corpse of Imogen, " Nay, Cadwal, we must lay

his head to the east: My father hath a reason for't."

^ In two barrows, in South "Wilts, the skeleton was found on

such a hollowed trunk or plank of wood, which Sir R. C.

Hoare expressly says was that of the elm. One of these was

in the "Winterbonrne Stoke group, the other was a very large

and fine barrow close to Stonchenge. " Ancient "Wilts," vol. i.

pp. 122, 124, 205. The elm, 2000 or 2500 years ago, might,

at least equally as now, deserve the name of the " Wiltshire

weed."

(6)

ANCIENT BRITISH—KENNBT, NORTH WILTS.

which, with the adhering bark, were found beneath the skeleton, to the bones of which it had imparted

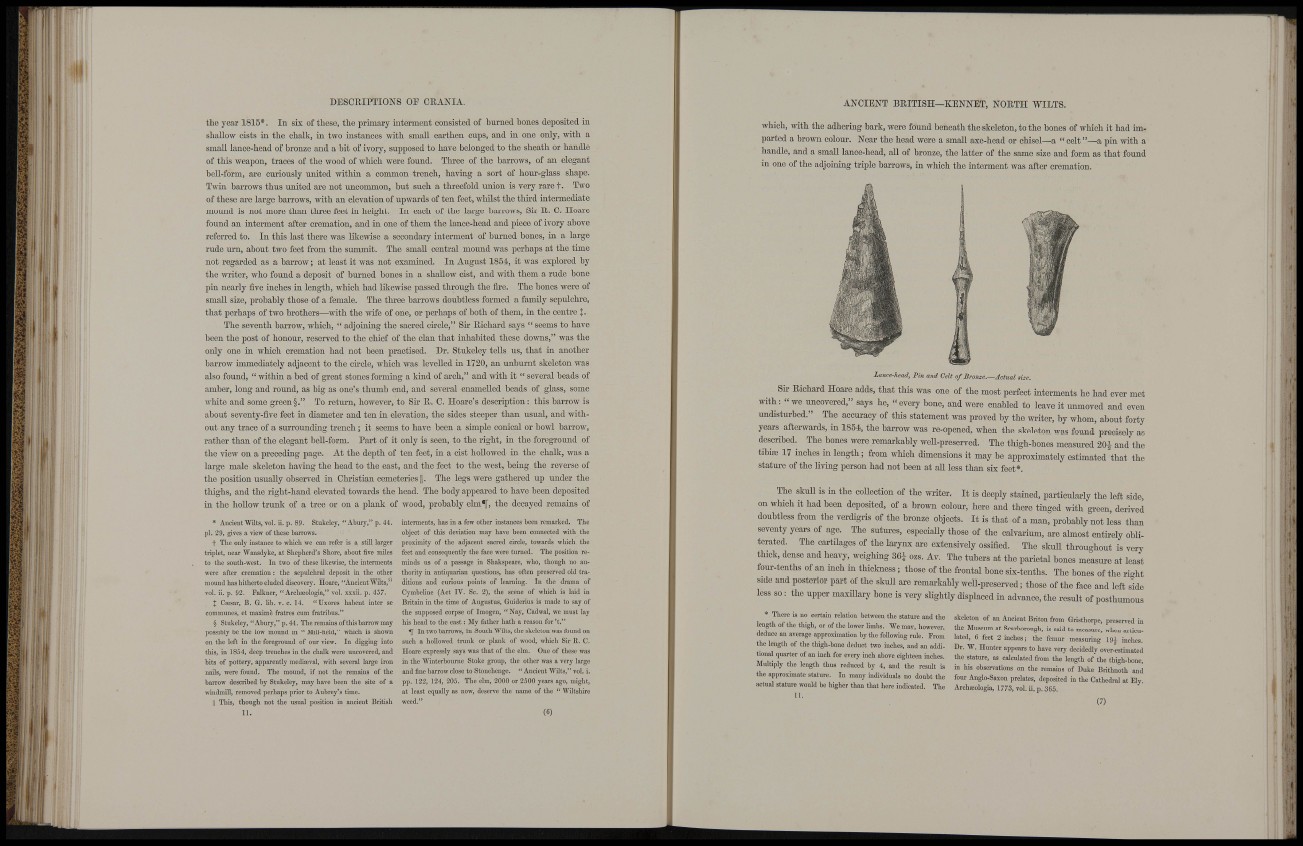

a brown colour. Near the head were a small axe-head or chisel—a " celt "—a pin with a

handle, and a small lance-head, all of bronze, the latter of the same size and form as that found

in one of the adjoining triple barrows, in which the interment was after cremation.

Lance-head, Pin and Celt of Bronze.—Actual size.

Sir Richard Hoare adds, that this was one of the most perfect interments he had ever met

with: "we uncovered," says he, "every bone, and were enabled to leave it unmoved and even

undistm-hed." The accui-acy of this statement was proved by the wi-iter, by whom, about forty

years afterwards, in 1854, the barrow was re-opened, when the skeleton was found precisely as

described. The bones were remarkably weU-preserved. The thigh-bones measured 20i and the

tibiae 17 mches in length; from wliich dimensions it may be approximately estimated that the

statm-e of the Hving person had not been at aU less than sis feet*.

The skull is in the collection of the wi-iter. It is deeply stained, particularly the left side,

on wliich it had been deposited, of a brown colour, here and there tinged with green, derived

doubtless from the verdigris of the bronze objects. It is that of a man, probably not less than

seventy years of age. The sutm-es, especially those of the calvai-ium, are almost entirely obliterated.

The cartilages of the larynx ai-e extensively ossified. The skuU throughout is very

thick, dense and heavy, weighing 36i ozs. Av. The tubers at the parietal bones measure at least

fom-.tenths of an inch in thickness; those of the frontal bone six-tenths. The bones of the ri-ht

side and posterior pai-t of the skull are remarkably weU-preserved; those of the face and left side

less so : the upper maxillary bone is very slightly displaced in advance, the result of posthumous

* There is no certain relation between the stature and the

length of the thigh, or of the lower limbs. We may, however,

deduce an average approximation by the following rule. From

the length of the thigh-bone deduct two inches, and an additional

quarter of an inch for every inch above eighteen inches.

Multiply the length thus reduced by 4, and the result is

the approximate stature. In many individuals no doubt the

actual stature would be higher than that here indicated.

11.

skeleton of an Ancient Briton from Gristhorpe, presei-ved in

the Museum at Scarborough, is said to measure, when articulated,

6 feet 2 inches; the femur measuring 19-1- inches.

Dr. "W. Hunter appears to have very decidedly over-estimated

the stature, as calculated from the length of" the thigh-bone,

in his observations on the remains of Duke Brithnoth and

four Anglo-Saxon prelates, deposited in the Cathedral at Ely.

Archaiologia, 1773, vol. ii. p. 365.

(7)