DESCEIPTIONS OP CRANIA,

stones was too sliort, and was supplemented by a small stone wedged in between it and the

covering stone. Other stones, not used as supports, formed a kind of enclosure round the kistvaen

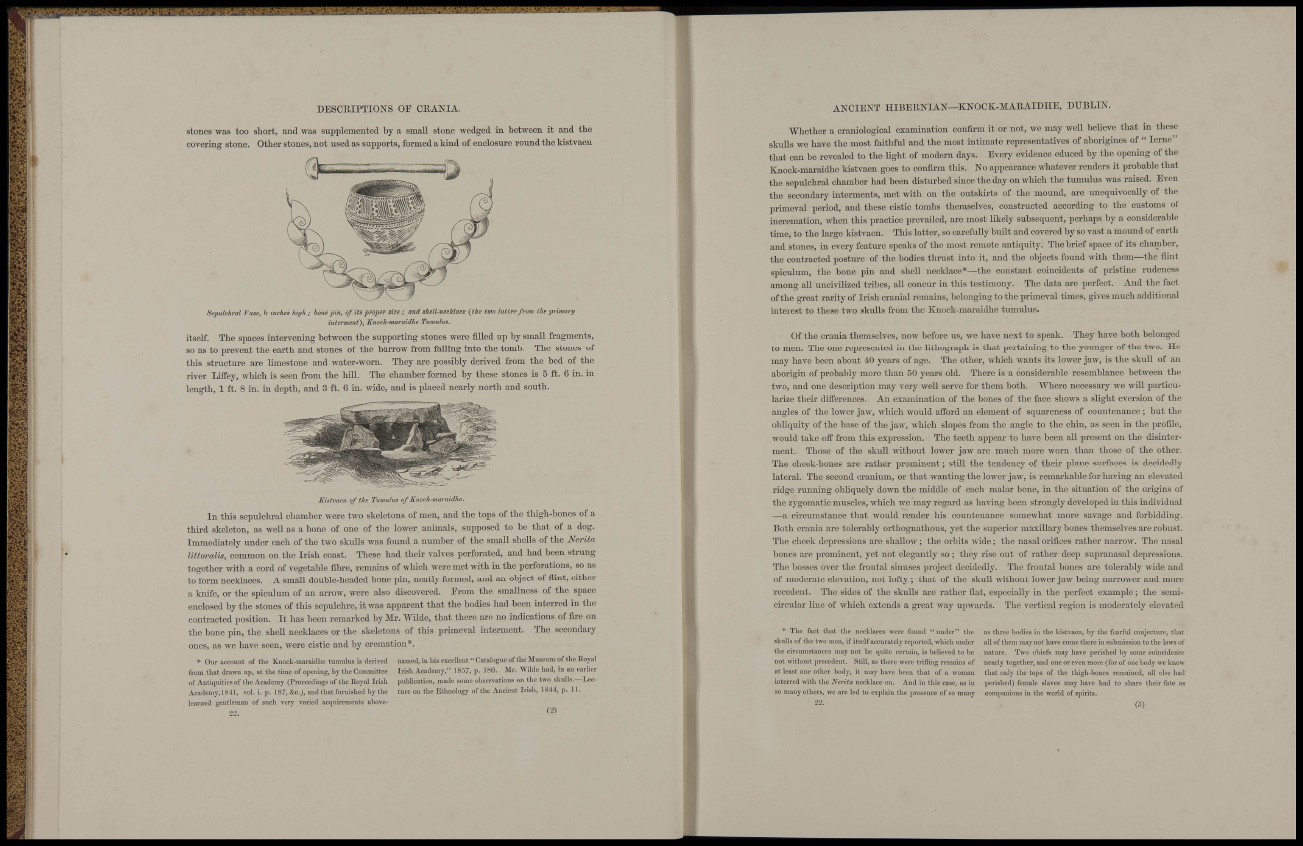

Fase, 6 inches high ; hone pin, of its proper sise ; and shell-necklaee {the two latter from the primary

interment'), Knock-maraidhe Tumulus.

itself. The spaces intervening between the supporting stones were flUed up by small fragments,

so as to prevent the earth and stones of the barrow from falling into the tomb. The stones of

this structure are limestone and water-worn. They are possibly derived from the bed of the

river Liffey, which is seen from the hill. The chamber formed by these stones is 5 ft. 6 in. in

length, 1 ft. 8 in. in depth, and 3 ft. 6 in. wide, and is placed nearly north and south.

Kistvaen of the Tumulus of Knock-maraidhe.

In this sepulchi-al chamber were two skeletons of men, and the tops of the thigh-bones of a

thii'd skeleton, as well as a bone of one of the lower animals, supposed to be that of a dog.

Immediately under each of the two skuUs was found a number of the small shells of the Nerita

Uttoralis, common on the Irish coast. These had their valves perforated, and had been strung

together with a cord of vegetable fibre, remains of which were met with in the perforations, so as

to form necklaces. A small double-headed bone pin, neatly formed, and an object of flint, either

a knife, or the spiculum of an arrow, were also discovered. Prom the smaUness of the space

enclosed by the stones of this sepulchre, it was appai-ent that the bodies had been interred in the

contracted position. It has been remarked by Mr. WUde, that there are no indications of fire on

the bone pin, the sheU necklaces or the skeletons of this primeval interment. The secondary

ones, as we have seen, were cistic and by cremation*.

* Our account of the Knock-maraidlie tumulus is derived

from that drawn up, at the time of opening, by the Committee

of Antiquities of the Academy (Proceedings of the Royal Irish

Academy,1841, vol. i. p. 187, &c.), and that furnished by the

learned gentleman of such very varied acqnu'ements above-

22.

named, in his excellent " Catalogue of the Museum of the Royal

Irish Academy," 1857, p. 180. Mr. Wilde had, in an earlier

publication, made some observations on the two skulls.—Lecture

on the Ethnology of the .\ncient Irish, 1844, p. 11.

(i)

ANCIENT HIBERNIAN—KNOCK-MAEAIDHE, DUBLIN.

Whether a craniological examination confirm it or not, we may well beUeve that in these

skulls we have the most faithful and the most intimate representatives of aborigines of " lerne"

that can be revealed to the light of modern days. Every evidence educed by the opening of the

Knock-maraidlie kistvaen goes to confirm this. No appearance whatever renders it probable that

the sepulchral chamber had been disturbed since the day on which the tumulus was raised. Even

the secondary interments, met with on the outsldrts of the mound, are unequivocally of the

primeval period, and these cistic tombs themselves, constructed according to the customs of

incremation, when this practice prevailed, are most lilcely subsequent, perhaps by a considerable

time, to the large kistvaen. This latter, so carefully built and covered by so vast a mound of earth

and stones, in every featm-e speaks of the most remote antiquity. The brief space of its chainber,

the contracted posture of the bodies thrast into it, and the objects found with them—the flint

spiculum, the bone pin and shell necklace*—the constant coincidents of pristine rudeness

among all uncivilized tribes, all concur in this testimony. The data are perfect. And the fact

of the great rarity of Irish cranial remains, belonging to the primeval times, gives much additional

interest to these two skulls from the Knock-maraidhe tumulus.

Of the crania themselves, now before us, we have next to speak. They have both belonged

to men. The one represented in the lithograph is that pertaining to the younger of the two. He

may have been about iO years of age. The other, which wants its lower jaw, is the skull of an

aborigin of probably more than 50 years old. There is a considerable resemblance between the

two, and one description may very well serve for them both. "WTiere necessary we wiU particularize

their differences. An examination of the bones of the face shows a slight eversión of the

angles of the lower jaw, which would aflbrd an element of squareness of countenance ; but the

obUqiiity of the base of the jaw, which slopes from the angle to the chin, as seen in the profile,

would take ofi' from this expression. The teeth appear to have been aU present on the disinterment.

Those of the skull without lower jaw are much more worn than those of the other.

The cheek-bones are rather prominent; still the tendency of their plane surfaces is decidedly

lateral. The second cranium, or that wanting the lower jaw, is remarkable for having an elevated

ridge running obliquely down the middle of each malar bone, in the situation of the origins of

the zygomatic muscles, which we may regard as having been strongly developed in this individual

—a circumstance that would render his countenance somewhat more savage and forbidding.

Both crania are tolerably orthognathous, yet the superior maxillary bones themselves are robust.

The cheek depressions are shallow; the orbits wide; the nasal orifices rather narrow. The nasal

bones are prominent, yet not elegantly so ; they rise out of rather deep supranasal depressions.

The bosses over the frontal sinuses project decidedly. The frontal bones are tolerably wide and

of moderate elevation, not lofty ; that of the skull without lower jaw being narrower and more

recedent. The sides of the skulls are rather flat, especially in the perfect example; the semicircular

line of which extends a great way upwards. The vertical region is moderately elevated

* The fact that the necklaces were found "under" the

skulls of the two men, if itself accurately reported, which under

the circumstances may not be quite certain, is believed to be

not without precedent. Still, as there were trifling remains of

at least one other body, it may have been that of a woman

interred with the Nerita necklace on. And in this case, as in

so many others, we are led to explain the presence of so many

22.

as three bodies in the kistvaen, by the fearful conjecture, that

all of them may not have come there in submission to the laws of

nature. Two chiefs may have perished by some coincidence

nearly together, and one or even more (for of one body we knowthat

only the tops of the thigh-bones remained, all else had

perished) female slaves may have had to share their fate as

companions in the world of spirits.