^ ill

DESCRIPTIONS OF CBAjS'IA.

lieing about four-tenths of an inch in thickness, and the frontal bone, around the eminences, not

less than half an inch. The skull is of large capacity, and is remarkable for its length in proportion

to its breadth, belonging dccidedly to the doKcho-cephalic class of Retzius. The form is slightly

deficient in symmetry. The forehead is narrow, contracted and rather receding, but not low:

a sort of central ridge is to be traced along the summit of the cranium, which is most marked in

front of the coronal suture, and falls away to a decidedly flat surface above each temporal ridge.

The very pyramidal aspect, thus given to the front view of the skull, is weU shown in our figure.

The parietal tubers are moderately prominent. The occiput is full, prominent and rounded, and

presents a strongly-marked transverse ridge. The squamous and mastoid portions of the temporal

bones are rather smaU; the external aiiditory openings are situated farther than usual

within the posterior half of the skull. The frontal siiiuses are very marked, and the glabella

moderately prominent; the nasal bones, of moderate size, project rather abruptly. The

insertions of the muscles of mastication are strongly marked, but neither the upper nor lower

jaw is so large, rugged, or angular as is often the case in skulls from ancient British tumuli.

Tlie malar bones are rather small, and the zygomata, though long, are not particularly prominent.

The ascending branch of the lower jaw forms a somewhat obtuse angle with the body of that

bone : the chin is poorly developed : the alveolar processes are short and small. In both jaws,

most of the incisor and canine teeth are wanting, but have evidently fallen out since death.

The molars and several of the bicuspids remain in their sockets. AH the teeth are remarkably

worn down, and the molars, especially those of the lower jaw, have almost entirely lost their

crowns; indeed, as respects the lower first molars, nothing but the fangs remain, round which

abscesses had formed, leading to absorption and the formation of cavities in the alveolar

process. The worn surfaces of the teeth are not flat and horizontal, but slope away obliquely

from without inwards, there being some tendency to concavity in the surfaces of the lower, and to

convexity in those of the upper teeth. The former are more worn on the outer, the latter on the

inner edge. Altogether the condition is such as we must attribute to a rude people subsisting

in great measm'e on the products of the chase and other animal food—Hi-provided with implements

for its division, and bestowing little care on its preparation—^rather than to an agricultural

tribe living chiefly on corn and fruits. Such we have reason to believe was the condition of the

early British tribes*. The state of these teeth, at least, contrasts decidedly with that observed in

Anglo-Saxon crania, in which, though the crowns of the teeth are often much reduced by

attrition, the worn surfaces are for the most part remarkably horizontal. The following are the

measurements of the skull.

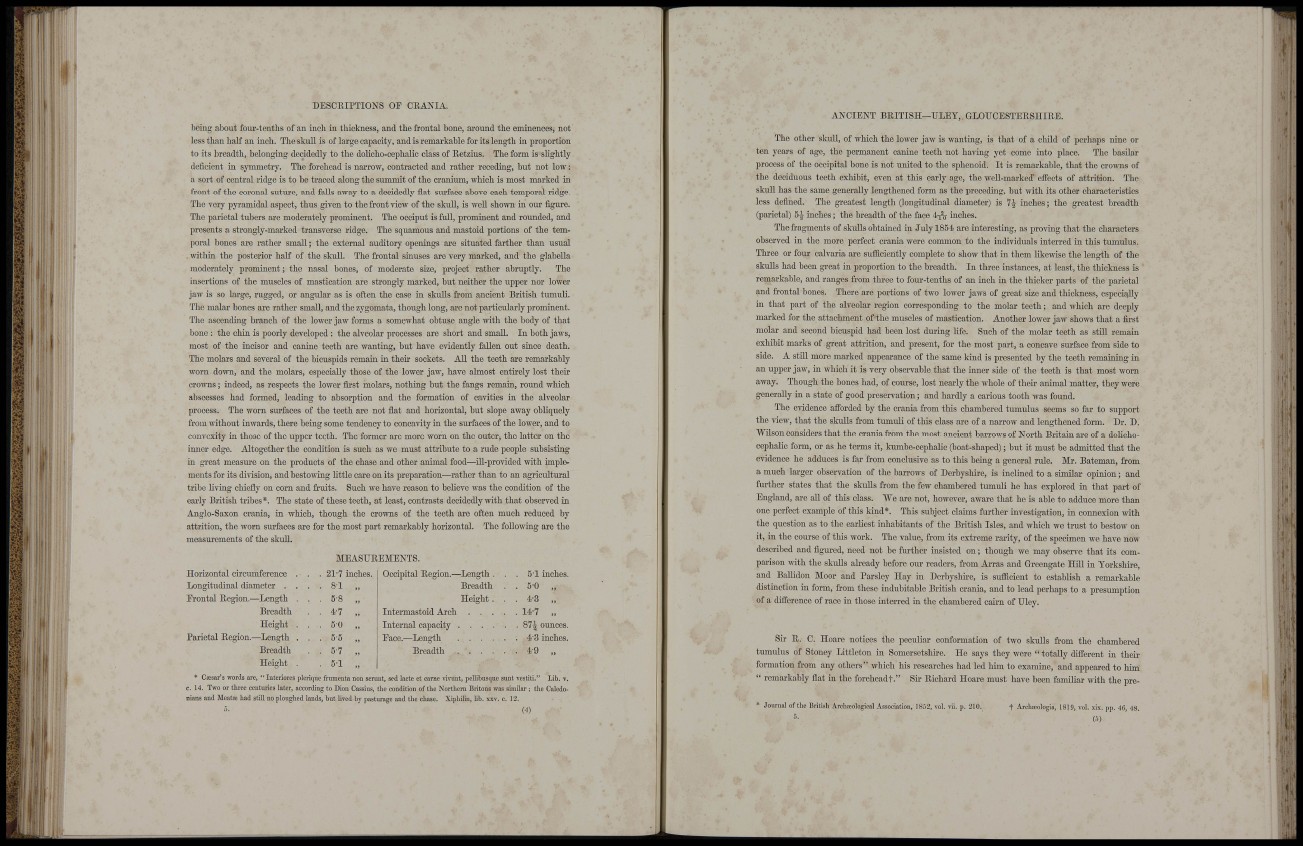

MEASUREMENTS.

Horizontal circumference . . 21-7 inches. Occipital Region.— -Length . . . 5-1 inches.

Longitudinal diameter . . . 81 » Breadth . 5-0 „

Erontal Region.—Length . . 5'8 is Height . . • 4-3 „

Breadth . 4-7 i ) Intermastoid Arch . 14-7 „

Height . . 50 3) Internal capacity . 87^ ounces.

Parietal Region.—Length . . 5-5 „ Eace.—Length . 4'3 inches.

Breadth . 5-7 5) Breadth • 4-9 „

Height . . 5-1

* Csesar's words are, " Interiores plerique frumenta non serunt, sed lacte et came virunt, pellibusque sunt vestiti." Lib. T.

e. 14. Two or three centuries later, according to Dion Cassius, the condition of the Northern Britons was similar ; the Caledonians

and Meatse had still no ploughed lands, but lived by pasturage and the chase. Xiphilin, lib. xxv. c. 12.

5. (4)

i M i k

ANCIENT BRITISH—ULEY, . GLOUCESTERSHIRE.

The other skuU, of which the lower jaw is wanting, is that of a child of perhaps nine or

ten years of age, the permanent canine teeth not having yet come into place. The basilar

process of the occipital bone is not united to the sphenoid, It is remarkable, that the crowns of

the deciduous teeth exhibit, even at this early age, the well-marked' effects of attrition. The

skuU has the same generally lengthened form as the preceding, but with its other characteristics

less defined. The greatest length (longitudinal diameter) is inches; the greatest breadth

(parietal) inches; the breadth of the face inches.

The fragments of skulls obtained in July 1854 are interesting, as proving that the characters

observed in the more perfect crania were cormnon to the individuals interred in this tumulus.

Three or four calvaria are sufliciently complete to show that in them likewise the length of the

skuUs had been great in proportion to the breadth. In tlu-ee instances, at least, the thickness is

remarkable, and ranges from three to fom'-tenths of an inch in the thicker parts of the parietal

and frontal bones. There are portions of two lower jaws of great size and thickness, especially

in that part of the alveolar region corresponding to the molar teeth; and which are deeply

marked for the attachment of the muscles of mastication. Another lower jaw shows that a first

molar and second bicuspid had been lost during life. Such of the molar teeth as stiU remain

exhibit marks of great attrition, and present, for the most part, a concave surface from side to

side. A still more marked appearance of the same land is presented by the teeth remaining in

an upper jaw, in which it is very observable that the inner side of the teeth is that most worn

away. Though the bones had, of com-se, lost nearly the whole of their animal matter, they were

generally in a state of good preservation; and hardly a carious tooth was found.

The evidence afforded by the crania from this chambered tumulus seems so far to support

the view, that the skulls from tumuli of this class are of a narrow and lengthened form. Dr. D.

Wilson considers that the crania from the most ancient barrows of North Britain are of a dolichocephalic

form, or as he terms it, kumbe-cephalic (boat-shaped); but it must be admitted that the

evidence he adduces is far from conclusive as to this being a general rule. Mr. Bateman, from

a much lai-ger observation of the barrows of Derbyshire, is inclined to a similar opinion; and

further states that the skulls from the few chambered tumuli he has explored in that part of

England, are aU of this class. We are not, however, aware that he is able to adduce more than

one perfect example of this kind*. This subject claims fm-ther investigation, in connexion with

the question as to the earliest inhabitants of the British Isles, and which we trust to bestow on

it, in the com-se of this work. The value, from its extreme rarity, of the specimen we have now

described and figured, need not be further insisted on; though we may observe that its comparison

mt h the skulls abeady before our readers, from Arras and Greengate HiU in Yorkshire,

and BalKdon Moor and Parsley Hay in Derbyshii-e, is suflicient to establish a remarkable

distinction in form, from these indubitable British crania, and to lead perhaps to a presumption

of a difference of race in those interred in the chambered cairn of Uley.

Sir R. C. Hoare notices the peculiar conformation of two skulls from the chambered

tumulus of Stoney Littleton in Somersetshire. He says they were " totally different in their

formation from any others" which his researches had led him to examine, and appeared to him

" remarkably flat in the foreheadf." Su- Richard Hoare must have been familiar with the pre-

* Journal of the British Archieological Association, 1852, vol. vii. p. 210.

5.

t .irchseologia, 1819, vol. xix. pp. 46,

(S)

m » J

I v

11

i

i'-'f.!. ?

i

• 1!.

iii- ;

,!L1

(r i

l i e

W,( • n •

m