i M

DESCRIPTIONS OP CRANIA.

bm-niiig of the dead was introduced at the time of Sylla, the Dictator, B.C. 78 ; who ordered his

body to he huined, contrary to the practice of the Cornelian gens, to which he belonged, and with

a view to prevent any insiolt to his remains. Erom this period cremation obtained prevalence,

tiU the beginning of the third century A.C., the age of the later Antonines, about wliich time

it is thought to have fallen into disuse.

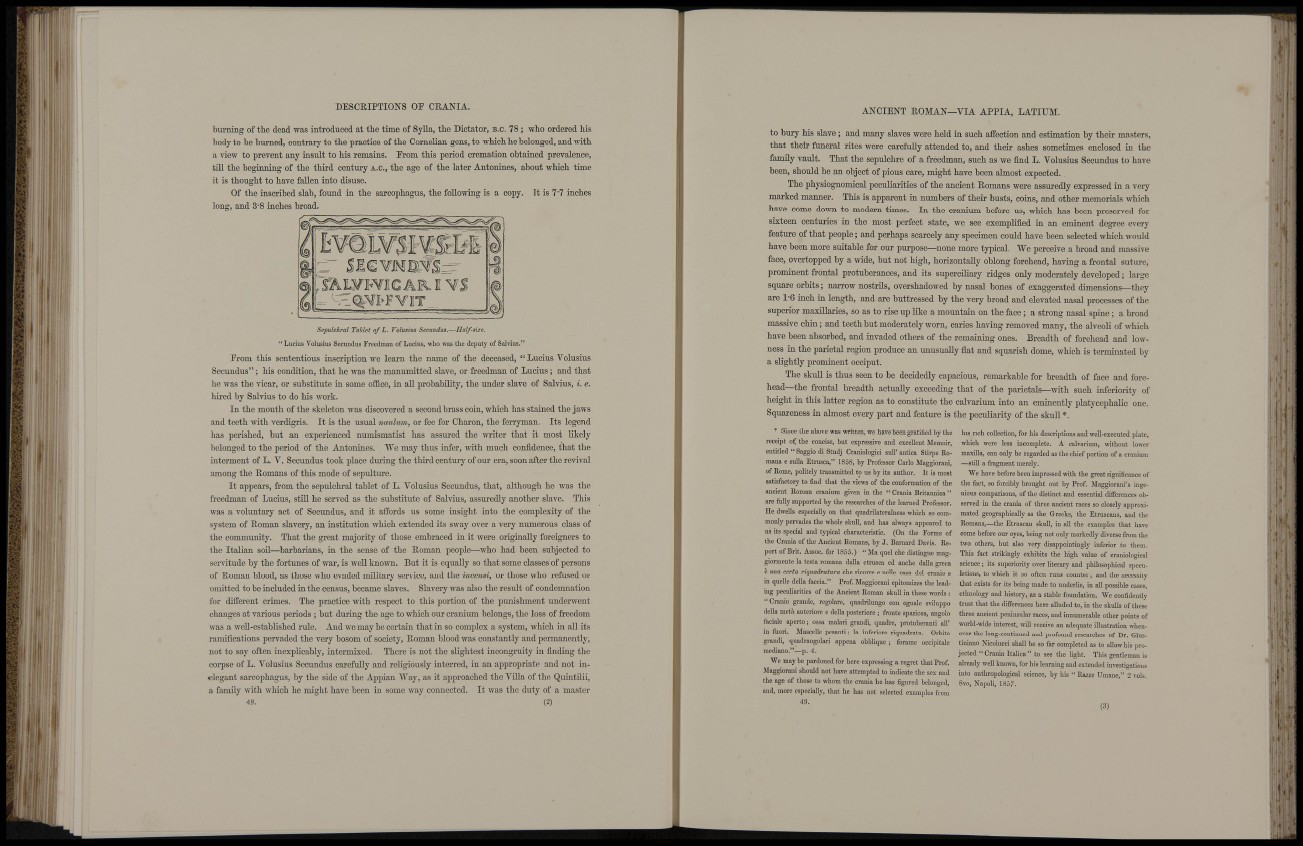

Of the inscribed slab, found in the sarcophagus, the following is a copy. It is 7'7 inches

long, and 3'8 inches broad.

Sepulchral Tablet of L. Volusius Secundus.—Half-size.

" Lucius Volusius Secundus Freedman of Lucius, who was the deputy of Salvius."

Prom this sententious inscription we learn the name of the deceased, " Lucius Volusius

Secundus" ; his condition, that he was the manumitted slave, or freedman of Lucius; and that

he was the vicar, or substitute in some office, in all probability, the under slave of Salvius, i. e.

hired by Salvius to do his work.

In the mouth of the skeleton was discovered a second brass coin, which has stained the jaws

and teeth with verdigris. It is the usual naulwm, or fee for Charon, the ferryman. Its legend

has perished, but an experienced numismatist has assured the writer that it most likely

belonged to the period of the Antonines. We may thus infer, with much confidence, that the

interment of L. V. Secundus took place during the third century of our era, soon after the revival

among the Romans of this mode of sepulture.

It appears, from the sepulchral tablet of L. Volusius Secundus, that, although he was the

freedman of Lucius, still he served as the substitute of Salvius, assuredly another slave. This

was a voluntary act of Secundus, and it affords us some insight into the complexity of the

system of Roman slavery, an institution which extended its sway over a very numerous class of

the community. That the great majority of those embraced in it were originally foreigners to

the Italian soil—barbarians, in the sense of the Roman people—who had been subjected to

servitude by the fortunes of war, is well known. But it is equally so that some classes of persons

of Roman blood, as those who evaded military service, and the mcensi, or those who refused or

omitted to be included in the census, became slaves. Slavery was also the result of condemnation

for different crimes. The practice with respect to this portion of the punishment underwent

changes at various periods ; but during the age to which our cranium belongs, the loss of freedom

was a well-established rule. And we may be certain that in so complex a system, which in all its

ramifications pervaded the very bosom of society, Roman blood was constantly and permanently,

not to say often inexplicably, intermixed. There is not the slightest incongruity in finding the

corpse of L. Volusius Secundus carefully and religiously interred, in an appropriate and not inelegant

sarcophagus, by the side of the Appian Way, as it approached the ViUa of the Quintilii,

a family with which he might have been in some way connected. It was the duty of a master

49. (2)

E

la

Ik

Ì

ANCIENT ROMAN—VIA APPIA, LATIUM.

to bury his slave; and many slaves were held in such affection and estimation by their masters,

that their funeral rites were carefully attended to, ajid their ashes sometimes enclosed in the

family vault. That the sepulchre of a freedman, such as we find L. Volusius Secundus to have

been, should be an object of pious care, might have been almost expected.

The physiognomical peculiarities of the ancient Romans were assuredly expressed in a very

marked manner. This is apparent in numbers of their busts, coins, and other memorials which

have come down to modern times. In the cranium before us, which has been preserved for

sixteen centuries in the most perfect state, we see exemplified in an eminent degree every

feature of that people; and perhaps scarcely any specimen could have been selected which would

have been more suitable for our purpose—^none more typical. We perceive a broad and massive

face, overtopped by a wide, but not high, horizontally oblong forehead, having a frontal suture,

prominent frontal protuberances, and its superciliary ridges only moderately developed; large

square orbits; narrow nostrils, overshadowed by nasal bones of exaggerated dimensions—they

are 1'6 inch in length, and are buttressed by the very broad and elevated nasal processes of the

superior maxUlaries, so as to rise up like a mountain on the face; a strong nasal spine ; a broad

massive chin; and teeth but moderately worn, caries having removed many, the alveoli of which

have been absorbed, and invaded others of the remaining ones. Breadth of forehead and lowness

in the parietal region produce an unusually flat and squarish dome, which is terminated by

a slightly prominent occiput.

The skull is thus seen to be decidedly capacious, remarkable for breadth of face and forehead—

the frontal breadth actually exceeding that of the parietals—with such inferiority of

height in tliis latter region as to constitute the calvarium into an eminently platycephalic one.

Squareness in almost every part and feature is the peculiarity of the skull *.

* Siuce the above was written, we have been gratified by the

receipt o£ the concise, but expressive and excellent Memoir,

entitled " Saggio di Studj Craniologici snll' antica Stirpe Romana

e suEa Etrusca," 1858, by Professor Carlo Maggiorani,

of Home, politely transmitted to us by its author. It is most

satisfactory to find that the views of the conformation of the

ancient Roman cranium given in the " Crania Britannica "

are fully supported by the researches of the learned Professor.

He dwells especially on that quadrilaterahiess which so commonly

pervades the whole skull, and has always appeared to

us its special and typical characteristic. (On the Forms of

the Crania of the Ancient Romans, by J. Barnard Davis. Report

of Brit. Assoc. for 1855.) "Ma quel che distingue maggiormente

la testa romana dalla etrusca ed anche dalla greca

è ma certa riquadratura che ricorre e nelle ossa del cranio e

in quelle della faccia." Prof. Maggiorani epitomizes the leading

pecuUarities of the Ancient Roman skull in these words :

"Cranio grande, regolare, quadrilungo con eguale sviluppo

della metà anteriore e della posteriore ; fronte spaziosa, angolo

faciale aperto ; ossa malari grandi, quadre, protuberauti all'

in fuori. Mascelle pesanti ; la inferiore riquadrata. Orbite

grandi, quadrangolari appena obbhque ; forame occipitale

mediano."—p.

We may be pardoned for here espressing a regret that Prof.

Maggiorani should not have attempted to indicate the sex aud

the age of those to whom the crania he has figured belonged,

and, more especially, that lie has not selected examples from

49.

his rich collection, for his descriptions and well-executed plate,

which were less incomplete. A calvarium, without lower

maxilla, can only be regarded as the chief portion of a cranium

—still a fragment merely.

We have before been impressed with the great significance of

the fact, so forcibly brought out by Prof. Maggiorani's ingenious

comparisons, of the distinct and essential differences observed

m the crania of three ancient races so closely approximated

geographically as the Greeks, the Etruscans, aud the

Romans,—the Etruscan skull, in all the examples that have

come before our eyes, being not only markedly diverse from the

two others, but also very disappointingly inferior to them.

This fact strikingly exhibits the high value of crauiological

science; its superiority over hterary and philosophical speculations,

to which it so often runs counter; and the necessity

tliat exists for its being made to underlie, in all possible cases,

ethnology aud history, as a stable foundation. We confidently

trust that the differences here alluded to, in the skulls of these

three ancient peninsular races, and innumerable other points of

worid-widc interest, will receive an adequate illustration whenever

the long-continued and profound researches of Dr. Ginstiniano

Nicolucci shall be so far completed as to allow his projected

"Crania Italica" to see the hght. This gentleman is

already well known, for his learning and extended investigations

into anthropological science, by his " Razze Umane," 2 vols.

8vo, Napoli, 1857.

(3)

f T P

•J,"

Ms

M : ^

K l

it:

; r < .

I l i ;

y

i W

jiji^tj^'

íi'l'