find certain trees on which to' rub his horns and.e§j|ur them is absurd. ' His mOtta is the same

as Longfellow’s :— . ■ . '

That is best which lieth nearest;

and when instinct p i s him that the horns are complete and the velvet is becoming dry on

the surface, he simply rubs and cleans them on any substance that is raised from the grquiid|;

presenting a suitable roughness.

A stag in a park does not go and hunt out a tree whose colour he desires to transmit to

his bonnet, and he will just as soon rub against the boards protecting young trees, the palings

o f the park, whether iron or wood, or any old stump that comes handy. So the stag living

in fir, birch, or beech woods uses the tree that comes first, and may thereby colour his

horns to a certain extent. Exposure to the weather plays no small part in affecting the

invisible life which, I think, still exists in and on the surface o f the horn for some time after

it is clean, but o f this we at present know little.1 More than half the stags in Scotland never

touch a tree at all when they are cleaning, nor, in fact, are they near them.

I remember seeing a party o f about twenty-five at Guisachan in the middle o f August,

and eight or ten of them were cleaning their horns on rocks and grassy hummocks. During

1 Just as this work goes to press this point is very properly referred to in an editorial note on this subject in the Field. It .

was noticed that the deer in the Zoological Gardens frayed their horns annually against painted iron bars, and even then they

were of the normal colour. It concludes with the sensible suggestion that “ this is due to the chemical change or oxygenation

which takes place in the superficially deposited blood. (?) stains caused by fraying, as they gradually dry on exposure to the air

and get rubbed into the bony surface while still in a sensitive condition. The intensity of the colour will naturally vary in

this process o f rubbing I believe that very little colouring matter goes on to the horns, or

how is it we see stags with nearly white ones when the velvet has been off several days ?

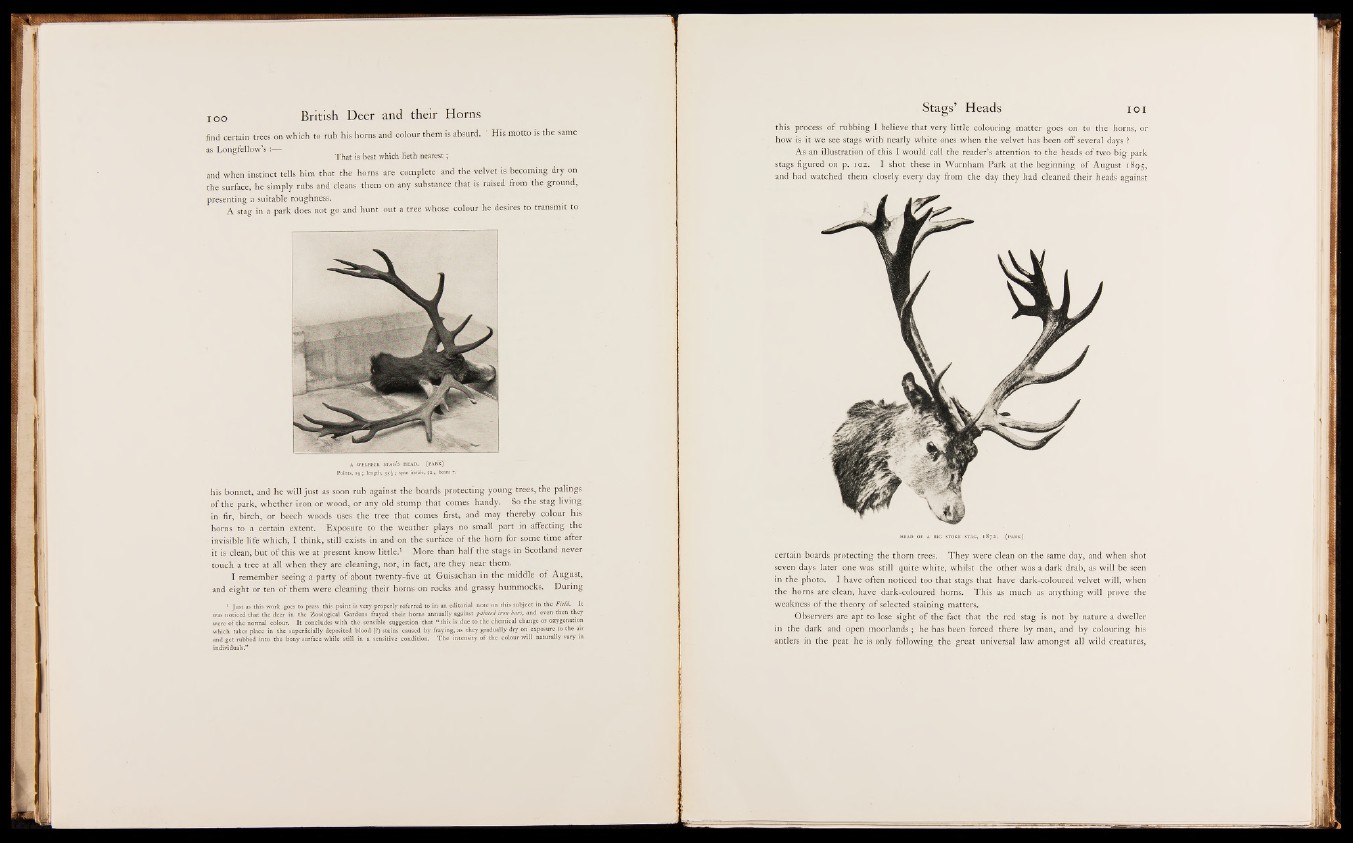

As an illustration o f this I would call the reader’s attention to the heads o f two big park

stags figured on p. 102. I shot these in Warnham Park at the beginning o f August 1895,

and had watched them closely every day from the day they had cleaned their heads against

certain boards protecting the thorn trees. They were clean on the same day, and when shot

seven days later one was still quite white, whilst the other was a dark drab, as will be seen

in the photo. I have often noticed too that stags that have dark-coloured velvet will, when

the horns are clean, have dark-coloured horns. This as much as anything will prove the

weakness o f the theory o f selected staining matters.

Observers are apt to lose sight o f the fact that the red stag is not by nature a dweller

in the dark and open moorlands ; he has been forced there by man, and by colouring his

antlers in the peat he is only following the great universal law amongst all wild creatures,