carefully distinguished from the “ horns ” of the bovine ruminants. These are outgrowths of true bone,

covered during their growth with vascular, sensitive integument coated with short hair, technically called

“ the velvet.” When the growth of the antler is complete, the supply of blood to it ceases, the skin dies

and peels off, leaving the bone bare and insensible, in which state it is well adapted for a fighting weapon.

After a time, by a process of absorption near the base, it becomes loosened from the skull and is shed.

A more or less elongated portion, called the “ pedicle,” always remains on the skull, from the summit of

which a new antler is developed. In most existing deer this process is repeated with great regularity at

the same period of the year. Even the great horns of the wapiti, and, judging by all analogy, those of

the Irish elk (Megaceros), the pair of which weigh 70 lbs., more than all the bones of the skeleton put

together, are produced in the course of three or four months.

According to all works on Natural History which I have read, the commencement o f

growth o f a stag’s new horns does not take place until the old ones are cast. Now I noticed

a very curious thing this spring, namely that the new skin and the epidermis beneath it do

commence to grow for some days before the old horns are shed.1 I had been carefully watching

a park stag in March a few days before he cast his hprns, and noticed a visible swelling below

the coronet which was slightly larger than the coronet itself. When the horns were cast, oh

15th March, this swollen mass o f epidermis and skin was therefore ready to overlap at once

the bare top o f the “ pedicle,” and as soon as the flaps on the summit joined, the bone commenced

to grow from the summit o f the pedicle. A few days later than this I went over

to Leonardslee, where Sir Edmund Loder was trying the effects o f some Mannlicher bullets.

He allowed me to shoot a Japanese stag, and the first thing I noticed was the distended state

o f the skin round the “ pedicle ” where the new epidermis was actually growing, for the

animal’s horns were just about to be shed.

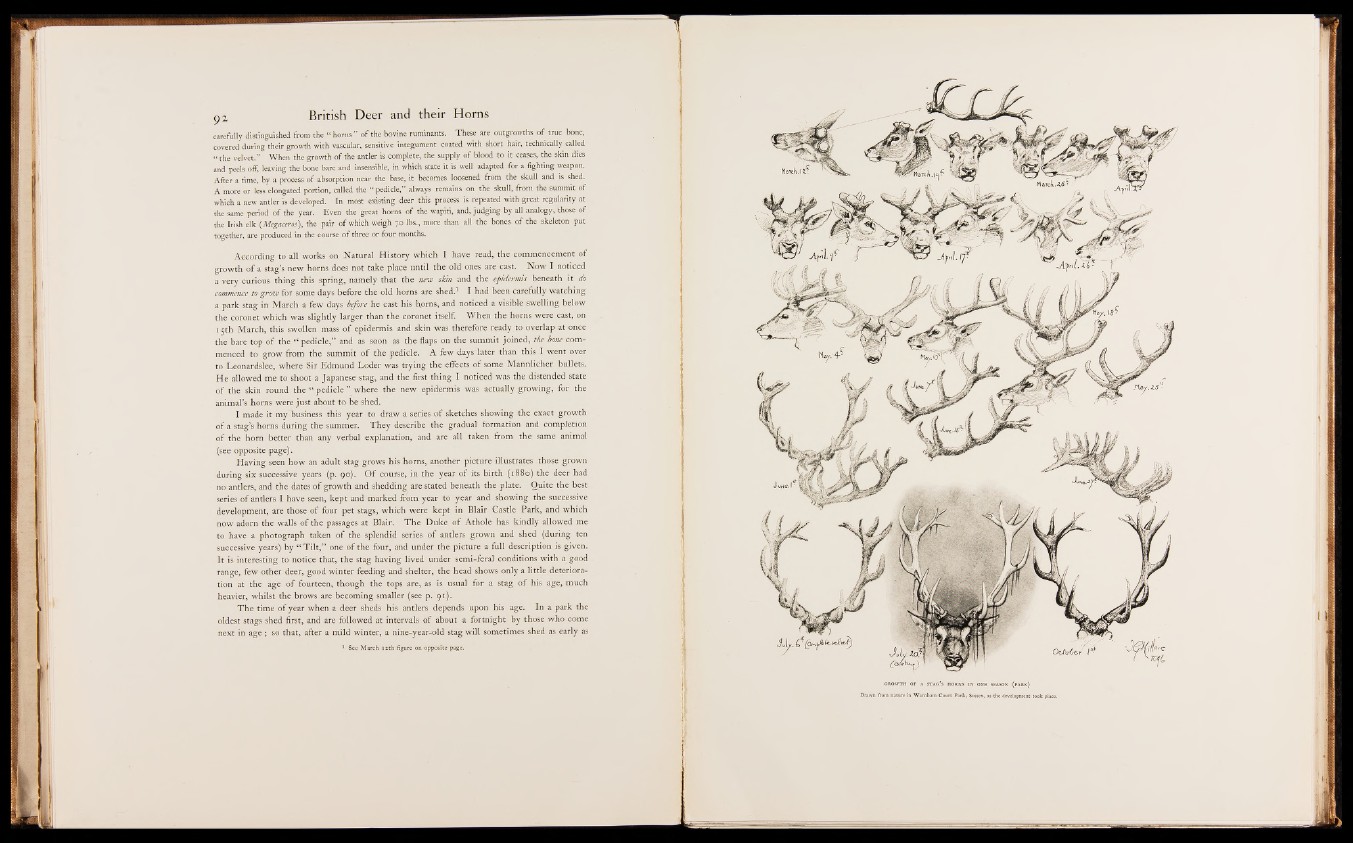

I made it my business this year to draw a series o f sketches, showing the exact growth

o f a stag’s horns during the summer. They describe the gradual formation and completion

o f the horn better than any verbal explanation, and are all taken from the same animal

(see opposite page).

Having seen how an adult stag grows his horns, another picture illustrates those grown

during six successive years (p. 90). O f course, in the year o f its birth (1880) the deer had

no antlers, and the dates o f growth and shedding are stated beneath the plate. Quite the best-

series o f antlers I have seen, kept and marked from year to year and showing the successive

development, are those o f four pet stags, which were kept in Blair Castle Park, and which

now adorn the walls o f the passages at Blair. T h e Duke o f Athole has kindly allowed me

to have a photograph taken o f the splendid series o f antlers grown and shed (during ten

successive years) by “ T ilt,” one o f the four, and under the picture a full description is given.

It is interesting to notice that, the stag having lived under semi-feral conditions with a good

range, few other deer, good winter feeding and shelter, the head shows only a little deterioration

at the age o f fourteen, though the tops are, as is usual for a stag o f his age, much

heavier, whilst the brows are becoming smaller (see p. 91).

The time o f year when a deer sheds his antlers depends upon his age. In a park the

oldest stags shed first, and are followed at intervals o f about a fortnight by those who come

next in age ; so that, after a mild winter, a nine-year-old stag w ill sometimes shed as early as

1 See March 12th figure on opposite page.