for fattening and horn-growing. Ha lf the park is reserved for hay, so the red deer, which

number about 100, have no great extent o f ground to range over, and very little winter

feeding. Nevertheless they thrive and have continued to improve steadily since 1884, when

the dressing was first tried, and at the present time a four-year-old Warnham stag is better

than an adult animal in most other English parks.

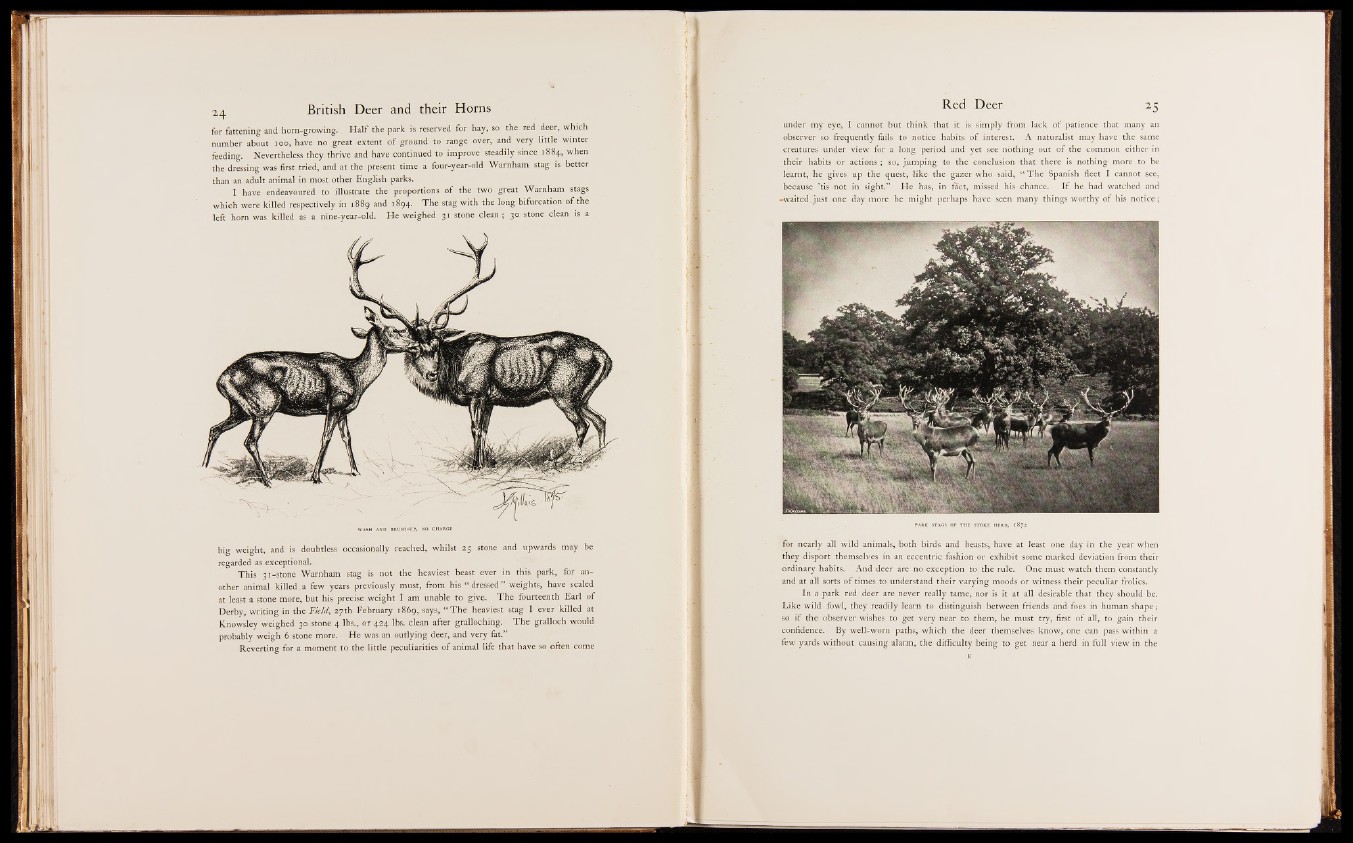

I have endeavoured to illustrate the proportions o f the two great Warnham stags

which were killed respectively in 1889 and 1894. The stag with the long bifurcation o f the

left horn was killed as a nine-year-old. He weighed 31 stone clean ; 30 stone clean is a

big weight, and is doubtless occasionally reached, whilst 25 stone and upwards may be

regarded as exceptional.

This 31-stone Warnham stag is not the heaviest beast ever in this park, for another

animal k illed. a few years previously must, from his “ dressed ” weights, have scaled

at least a stone more, but his precise weight I am unable to give. T h e fourteenth Earl o f

Derby, writing in the Field, 27th February 1869, says, “ T h e heaviest stag I ever killed at

Knowsley weighed 30 stone 4 lbs., or 424 lbs. clean after gralloching. T h e gralloch would

probably weigh 6 stone more. He was an outlying deer, and very fat.”

Reverting for a moment to the little peculiarities o f animal life that have so often come

under my eye, I cannot but think that it is simply from lack o f patience that many an

observer so frequently fails to notice habits o f interest. A naturalist may have the same

creatures under view for a long period and yet see nothing out o f the common either in

their habits or actions ; so, jumping to the conclusion that there is nothing more to be

learnt, he gives up the quest, like the gazer who said, “ T h e Spanish fleet I cannot see,

because ’tis not in sight.” He has, in fact, missed his chance. I f he had watched and

-waited.’just one day more he might perhaps have seen many things worthy o f his notice;

for nearly all wild animals, both birds and beasts, have at least one day in the year when

they dispt>rt themselves in an eccentric fashion or exhibit some marked deviation from their

ordinary habits.' And deer are no exception to the rule. One must watch them constantly

and at all sorts o f times to understand their varying moods or witness their peculiar frolics.

In a park red deer are never really tame, nor is it at all desirable that they should be.

Like wild fowl, they readily learn to distinguish between friends and foes in human shape;

so i f the observer wishes to get very near to them, he must try, first of all, to gain their

confidence. By well-worn paths, which the deer themselves know, one can pass within a

few yards without causing alarm, the difficulty being to get near a herd in full view in the