cabinet as a skin. Which, by the bye, recalls my poor father’s remark when some one was

chaffing me about writing a big volume on the subject o f grouse : “ Ah well, you can write

a book bigger than the Bible about bluebottles i f you only know enough about them”

Taking everything into consideration, the fallow deer is about the most satisfactory

animal we could possibly have in our parks. T hey are extremely beautiful, their venison

is first-rate, and they are never dangerous, the latter perhaps the most important o f all, for

one may say that, hardly without exception, the elaphine group are not to be implicitly

trusted i f allowed to become the least tame, whilst under such circumstances the sweet and

gentle-looking little roebuck is the very Devil himself.

Richard Jefferies pithily remarks that “ a park without deer is like a wall without

pictures,” and for those who live in the country and are so fortunate as to possess both, the

animals and their ways are a continual source o f enjoyment and interest.

In summer, provided the weather is warm and sunny, the fallow deer have their regular

times for rest and food, and are much the same in this respect as the red deer, but as a

general rule they are more restless, getting up and lying down again more frequently and

feeding for shorter periods ; particularly so is this the case in winter, when they do not rest

for nearly so long a period as their larger brethren, but split up into little groups and move

about, more particularly when food is scarce. Whitaker gives all directions for the feeding

o f fallow deer, etc., so there is next to nothing to be said on this subject. One curious

fact, however, on the subject o f their tastes is worth mentioning. During the very severe

winter o f 1894 the fallow deer in a certain Sussex park were somewhat neglected, and hay,

which constituted their only extra, was not put out for them until the heavy snow had

entirely covered the ground in December. The deer were by that time in a miserable

plight, and absolutely refused to touch the food that was put down for them— doubtless on

account o f the damp. T hey now began to practically die o f starvation, and it was noticed

the animals evinced a desire to get into the ground around the old ivy-covered mansion.

Some were allowed to do so. Once there they made straight for the ivy on the walls and

ravenously devoured it. After this all the leaf was shorn from the sides o f the house and

the deer were allowed in the garden. This stock o f food probably saved the greater number

o f the deer, for they refused all other food till the ivy was finished.

A wet spring or wet autumn is very fatal to fallow deer, as they contract liver fluke.

Some years ago at Savernake I remember seeing, I should think, nearly half the stock dead

or dying from this cause, and this on a fairly dry and sandy soil.

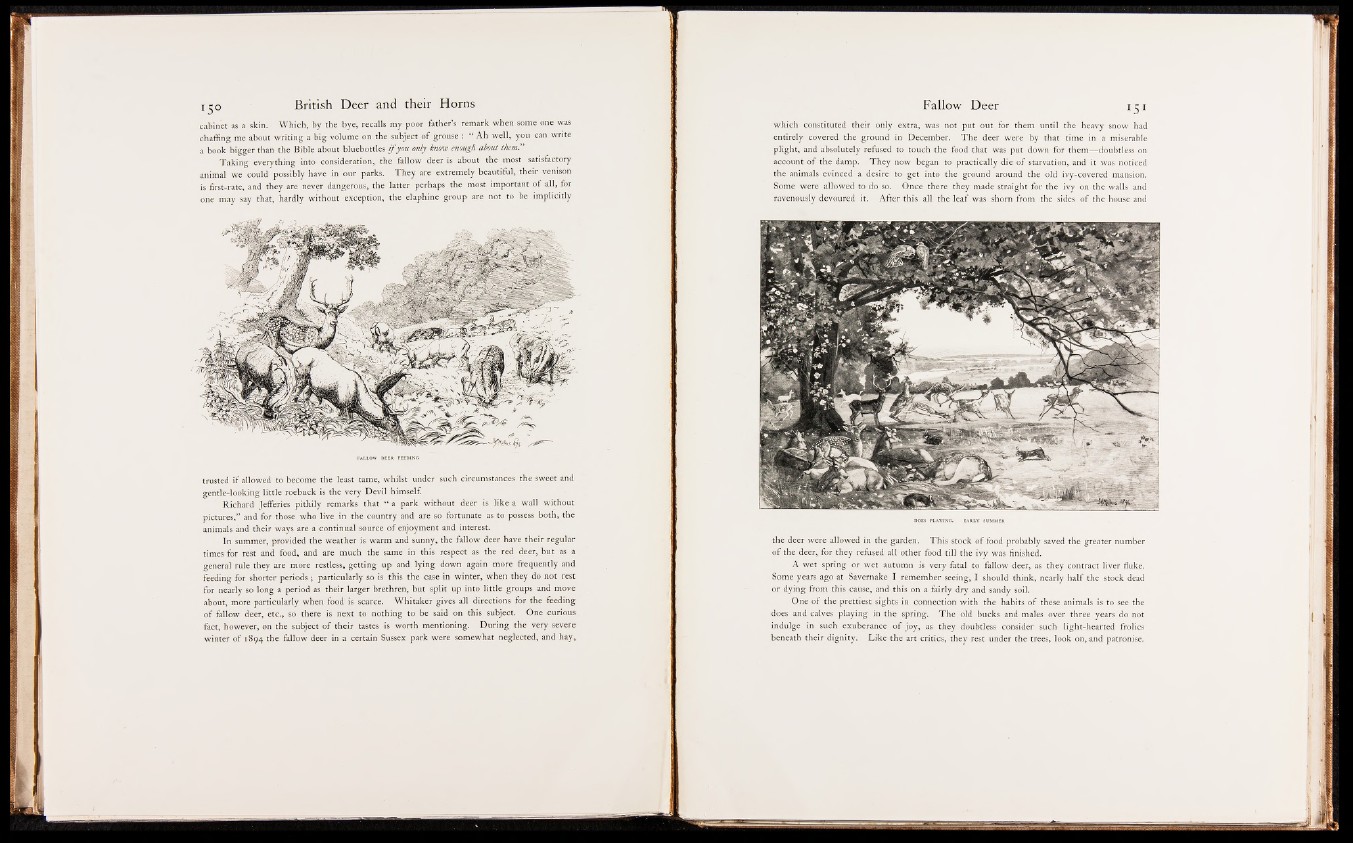

One o f the prettiest sights in connection with the habits o f these animals is to see the

does and calves playing in the spring. T h e . old bucks and males over three years do not

indulge in such exuberance o f joy, as they doubtless consider such light-hearted frolics

beneath their dignity. Like the art critics, they rest under the trees, look on, and patronise.